'Massive blindspot': Missing data in COVID pandemic leaves US vulnerable

There are more than 671,000 cases in the US. Experts worry it's much higher.

President Donald Trump is giving states the green light to reopen their governments as they see fit.

Governors on both coasts -- some of the hardest-hit areas thus far -- are also discussing plans to get the economy rolling again.

But the big question is when and how to do so safely.

While discussions about flattening the curve, passing the peak and plateauing have generated some optimism, public health professionals fear that a key factor in understanding the novel coronavirus pandemic has been forgotten: the missing data.

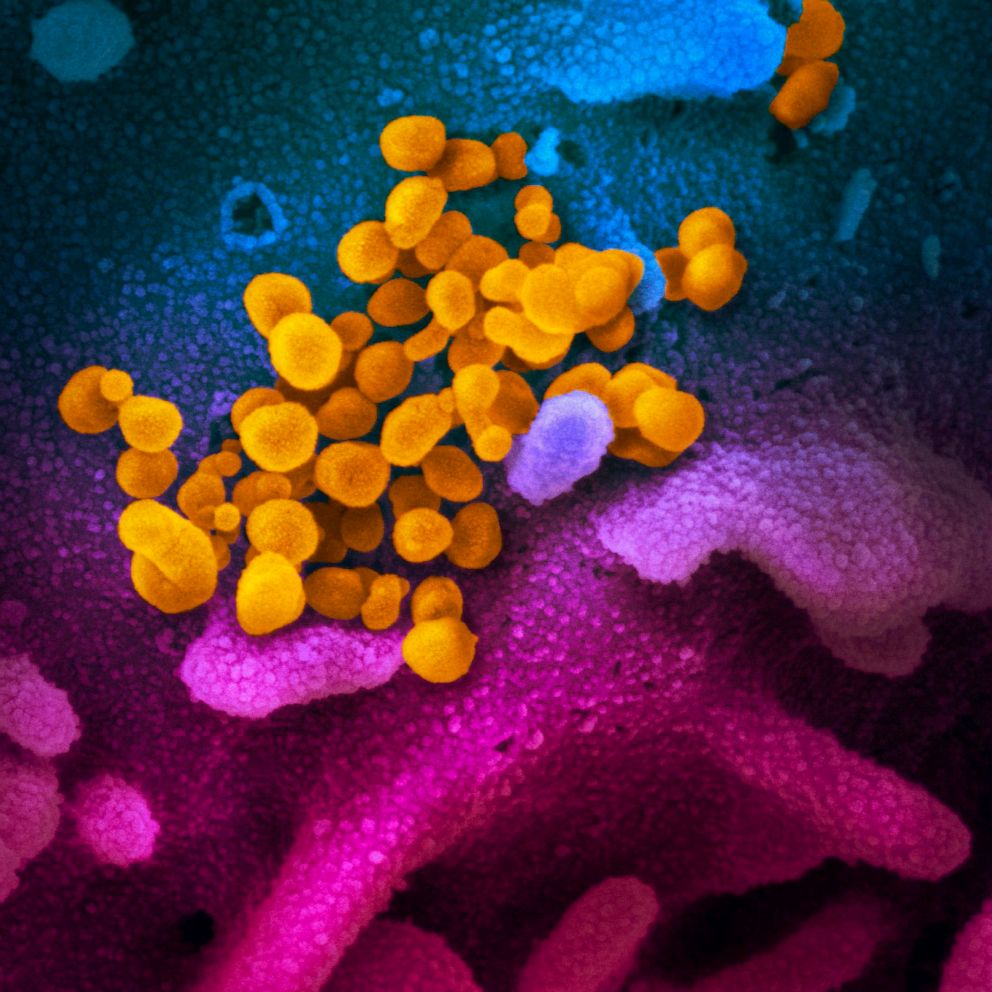

There are at least 671,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the United States, according to data compiled by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering at Johns Hopkins University. However, experts have warned that the number is likely much higher because testing has been sparse.

"We, in the U.S., have a massive blindspot because of the lack of testing," Dr. John Brownstein, an epidemiologist at Boston Children's Hospital and an ABC News contributor who worked on a website to help bridge the data gap, told ABC News. "We've not really had a deep understanding of the amount of illness that happened in the community."

"Without knowing, it creates a real barrier to us to be able to effectively model and project out the epidemic in the U.S. because we need to understand how much infection has taken place," Brownstein added.

Brownstein believes the number of cases in the U.S. is more likely in the millions. He said through the website he helped create, which allows the public to self-report any symptoms, some 400 people who responded (out of the 400,000 who used it) said they tested positive for COVID. But 4,000 displayed all the symptoms of the disease. The most severe cases may include fever, heavy dry cough, and serious breathing issues that can lead to hospitalization or even death. While 80% of cases are believed to have mild or no symptoms at all.

"The majority of people, at least 10x or more, who were displaying COVID symptoms said they were not tested," he said.

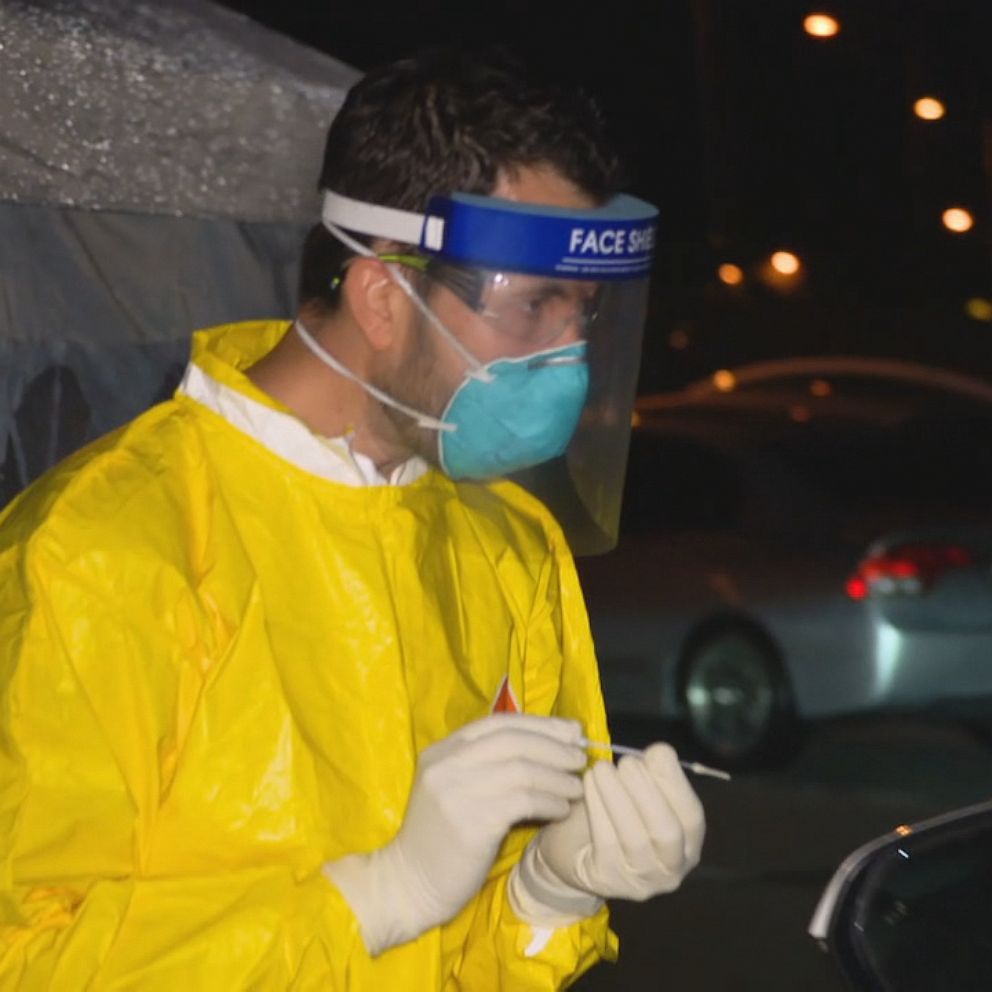

Out of the estimated 329 million people who live in the country, only 3.2 million have been tested, according to the Johns Hopkins data. Although efforts have been ramped up across the country, including drive-thru centers, there are many people with symptoms who have not been tested, in some cases to preserve both the tests and PPE for those conducting the tests for the sickest individuals. Tests generally involve using a nasal swab that can cause people to cough and sneeze, requiring providers to wear protective equipment.

Rapid testing has not been rolled out widely, and saliva testing, which does not carry the same PPE requirements, was authorized by the FDA on April 15.

Antibody testing, which may identify those that have been exposed to the virus and recovered, also is not widespread, although there are efforts in several states. Antibody testing would give a truer sense as to how widespread the infection was in the U.S.

In New York, the state with the most cases, testing has mainly been reserved for those who are severely ill and hospitalized. In Washington state, where one of the first U.S. hotspots was recorded, health care providers are directed to only test those with COVID-19 symptoms, including fever, cough, or shortness of breath.

However, the situation is a bit of a catch-22.

As Brownstein explained, there are also people who are displaying symptoms that are not part of what he called the "case definition." Those people, because they don't fall in line with the listed symptoms, are not being tested in large numbers and therefore the range of symptoms officially associated with COVID is limited. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevent, for instance, lists fever, cough and shortness of breath as the principal symptoms.

The missing data also makes it difficult to understand how the virus is affecting people of different ages, races and sexes. Until last week and under pressure, the CDC released a limited dataset that included race and even those results revealed that African Americans appeared to be disproportionately affected -- 33% of the hospitalizations despite being 13% of the population.

Even states that have been tracking racial and other demographic data only recently started releasing that information and some of it is notably incomplete, with race either not reported or unknown.

With all the missing information, Brownstein said it's hard to feel optimistic about the possibility of flattening the curve -- the concept of spreading out the cases that hit the hospital system over time so that resources aren't taxed, better care can be provided, and a second wave of cases is prevented in the future.

Tune into ABC at 1 p.m. ET and ABC News Live at 4 p.m. ET every weekday for special coverage of the novel coronavirus with the full ABC News team, including the latest news, context and analysis.

"When we don't have the true insight of testing, when testing is uneven and not comprehensive, it creates a fear on the part of public health that we may be relying on imperfect data to make decisions," Brownstein said.

He did note that if the number is in the millions, it offers a promising sign that the majority of people infected have not experienced severe cases.

Even that appears uncertain. Initial data coming out of China, where the pandemic appears to have started, was that 80% of cases were mild. But it's hard to know the true hospitalization rate or death rate without knowing the estimated total number of cases.

Dr. Angela Rasmussen, a virologist and associate research scientist at Columbia University's Center for Infection and Immunity, similarly said that the lack of data leaves the U.S. vulnerable when trying to understand the virus and make decisions going forward.

Unlike Brownstein, Rasmussen said it is too difficult to quantify the amount of data we're missing.

"I'll just say that we're missing a lot both in terms of people who are infected, as well as people who were previously infected," Rasmussen told ABC News.

One of the biggest questions is immunity -- whether those who have been exposed to the virus or recovered from the disease are protected, and for how long.

"We don't know if having the virus makes you immune," Rasmussen said. While the data so far suggests those who have been infected would be immune, "we actually still don't know very much about immunity," she added.

"It's a pretty substantial piece of missing data. I don't think we can absolutely make the assumption that just having the antibodies means it's cool to go back to normal," Rasmussen said.

In order to safely reopen the country in the midst of a pandemic for which there is no vaccine or cure, she said there would need to be clear plans in terms of surveillance and testing -- neither of which she has heard a plan for.

She said surveillance, which is often used for influenza, can consist of people giving samples and testing those samples to see if any are positive. From there, if any are positive results, labs will then test each sample to find the positive result and track the case from there.

Experts estimate that a robust contact tracing program, to monitor and stamp out outbreaks and help open up the economy could mean spending $3.6 billion and hiring 100,000 workers. Tracing systems are used to track the flu and other contagious diseases.

Surveillance can also be done through apps. However, Rasmussen noted that relies on people self-reporting their symptoms, which she said can be tricky. She said apps might be better served to identify people who have tested positive for COVID and trace their contacts.

Either way, she said, without the ability to track infection in a community, the U.S. could be "back to square one."

What to know about coronavirus:

- How it started and how to protect yourself: Coronavirus explained

- What to do if you have symptoms: Coronavirus symptoms

- Tracking the spread in the U.S. and worldwide: Coronavirus map

"If you have a percentage of the population that is infected, that you can't identify, that leads us to a point where we would back to square one where there's community transmission occurring that we don't know about and therefore we can't isolate those people that are infected," Rasmussen said.

"This is something that requires a ton of data and requires to make data-driven decisions," she added. "And we need to have data before we can actually do that."