People are going to protest George Floyd's death. Here's how to do so more safely.

Law enforcement also has a role to play in stopping COVID-19's spread.

As cities and towns across the country continue to protest George Floyd's death at the hands of police, health authorities' advice to demonstrators has shifted from "stay home to stop the spread" to tips on how to protest more safely during a pandemic.

While the biggest protests have slowed down since the officers in the case were charged and Floyd's funeral, groups still marched in New York City Thursday and maintained an "autonomous zone" in Seattle.

The changing recommendations are essentially a form of harm reduction, or public health policy designed to minimize health risk for people engaging in potentially dangerous activities.

"Staying indoors all the time in a pandemic is equivalent to an abstinence-only policy," Kimberly Sue, medical director of the Harm Reduction Coalition, a nonprofit that advocates for initiatives like needle exchanges to minimize harm associated with drug use.

Harm reduction involves making individual risk-benefit calculations about safety, Sue explained, which isn't a one-size-fits-all strategy.

While the risk of COVID-19 transmission during outdoor demonstrations is lower than it would be indoors, mass protests could still potentially spread the virus, health experts have warned.

"As an infectious disease specialist, I would say [protests] will result in infections," said Rupa Patel, an infectious disease doctor and director of the pre-Exposure prophylaxis for HIV (PrEP) program at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

"I don't want to be pinned down," she added. Telling protesters not to demonstrate "would violate my inner core."

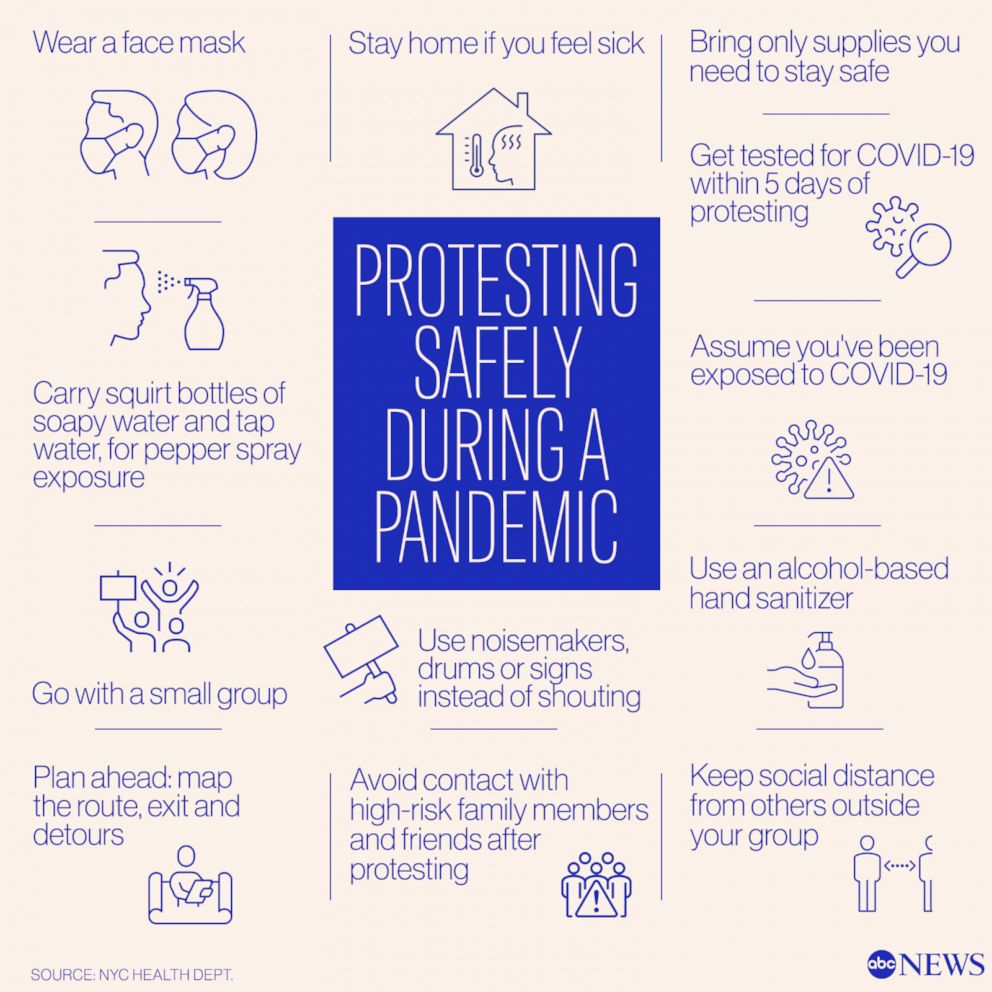

To mitigate COVID-19 risk, a few forward-thinking public health departments have put out guidelines for how to protest more safely during the pandemic.

New York City's Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, for example, recommends that protesters fully cover their mouths and noses with face masks while demonstrating. Carrying signs and utilizing noisemakers rather than shouting, is another way to slow the spread of the disease, which can be transmitted through respiratory droplets.

Go with a small group and have a plan, the guidance continues. Outside of their small group, protesters should do their best to maintain physical distance between themselves and others whenever possible. If you do become ill, knowing who is around you allows you to let others know they should also get tested for COVID-19.

Demonstrators should also be prepared with hand sanitizer, water, snacks and needed medication, as well as squirt bottles of soapy water and tap water, for rinsing their eyes if they are exposed to pepper spray, the health department recommends.

Importantly, if protesters aren't feeling well, they should stay home and take action in other ways, like voting, supporting local community groups and contacting their legislators.

Although "harm reduction" is sometimes narrowly used to describe needle exchange programs designed to limit the spread of HIV and hepatitis C for people who use drugs, the term itself applies to a broad set of policies designed to help people make safe choices.

At its core, harm reduction acknowledges that some people inevitably take risks. In the case of people who use drugs, for example, it's safer to help mitigate the risk of infection and death by offering sterile supplies and overdose antidotes than it is to suggest that the only alternative to drugs is sobriety.

For her part, Patel says the core tenants of harm reduction fit into public health doctors’ broader obligation to protect human rights while also helping people stay safe.

"You’re describing a broader human rights-based approach to policy and medicine," Patel said. "These are the tenants of human rights."

Health departments and government leaders have also begun recommending that anyone who protests get tested for COVID-19 within a week of possible exposure to the virus.

"If you were at a protest, get a test," New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo said during a press conference last week. "It's free, it's available," he reiterated on Monday, noting that 15 testing sites in New York are specifically dedicated to test protesters.

The majority of people who are infected with coronavirus develop symptoms within 14 days of being infected and since asymptomatic carriers can spread the disease before feeling sick, there's only a short window for getting testing and slowing the spread of the virus.

"If you were out protesting last night, you probably need to go get a COVID test this week," Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms said during a news conference in late May.

"There's still a pandemic in America that's killing black and brown people at higher numbers."

Regardless of the COVID-19 precautions protesters take, there is still a degree of unavoidable risk inherent in mass demonstrations. But staying home from protests against racism is also a risk, since the same structural racism that results in black men disproportionately dying at the hands of police officers fuels racial disparities in COVID-19 deaths, according to Leo Beletsky, a professor of law and health sciences at Northeastern University.

In New York City, COVID-19 death rates among African Americans were roughly double the rates among their white counterparts, according to the Centers for Disease and Prevention.

"There’s broad recognition that racism is one of the top public health issues of our time," Beletsky said.

While health experts who criticize the protests because they could spark infections might be well-intentioned, "they fail to grasp that racism is the underlying cause of both COVID-19 and police violence, as well as asthma, overdose and maternal mortality rates," he added.

"All of those health issues exhibit a stark racial gradient."

The point wasn't lost on the individual running the New York City health department's Twitter account.

"Racism is a public health problem," the health department tweeted Monday. "In New York City, Black and Brown communities face the disproportionate impact, grief and loss from the COVID-19 pandemic on top of the trauma of state-sanctioned violence."

Law enforcement also has a responsibility to slow COVID-19's spread

While protesters should continue to take personal responsibility for slowing the spread of COVID-19 by wearing masks, using hand sanitizer and getting tested, law enforcement also has a duty to stop the spread, Beletsky said.

Police tactics like kettling, mass arrests, and using tear gas and pepper spray, which cause coughing, increase the risk that the virus will spread during protests, experts say.

There's also the issue of police officers themselves not wearing face masks, including in New York City, the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak.

"I’m frustrated by it, too," New York Mayor Bill de Blasio told WNYC, when asked why officers in the city weren't wearing masks.

"The policy is police officers are supposed to wear face coverings in public, period," he said.

"It’s indicative of this toxic culture in policing, where people just are not taking precautionary measures," Beletsky said. "There’s a sense that police officers are somehow invincible."

Police officers are far from immune to coronavirus. At least 45 members of the New York City Police Department who were infected with the virus have died.

"It not only shows total disregard for the individual health of the protesters, but it's also a huge mistake from an occupational safety standpoint," Beletsky said. "This is an illustration that police culture tends to think of officers as exceptional and above the rules."

While a few health departments, including New York City's and Minnesota's, have published guidance for protesters on demonstrating safely in recent days, countless others have remained silent.

"I think there’s a very difficult dynamic where stating any support for protests or creating any infrastructure to help protesters or take care of protesters is seen as anti-police," Beletsky said.

That proved true in Asheville, North Carolina, last week, when the police department attacked a medical tent that was set up for protesters and staffed by health workers.

Officers in riot gear stabbed water bottles with knives and destroyed $700 worth of supplies, including bandages and saline solution, Sean Miller, head of communications for the medical team and a student at the University of North Carolina Asheville told the Asheville Citizen Times.

"I am aware of the incident involving officers destroying the medical supplies of demonstrators, including water bottles, food, and other supplies," Asheville Mayor Esther Manheimer wrote on Facebook.

"This was a disappointing moment in an otherwise peaceful evening."

What to know about the coronavirus:

- How it started and how to protect yourself: Coronavirus explained

- What to do if you have symptoms: Coronavirus symptoms

- Tracking the spread in the U.S. and worldwide: Coronavirus map

Tune into ABC at 1 p.m. ET and ABC News Live at 4 p.m. ET every weekday for special coverage of the novel coronavirus with the full ABC News team, including the latest news, context and analysis.