'Such a privilege' to donate convalescent plasma: Reporter's Notebook

ABC News correspondent Kaylee Hartung shares her personal coronavirus story.

ABC News correspondent Kaylee Hartung was diagnosed with COVID-19 six weeks ago. She’s now recovered from the virus. She shares her first-person account of donating convalescent plasma to help others in their fight against the coronavirus.

When COVID-19 attacked me, the hardest blow it dealt me was the helplessness it made me feel. Suddenly I was isolated, physically and emotionally. That was far more crippling than the headaches, even the backaches.

But today I can say I've never felt stronger. Until I one day give birth to a child, I can't imagine my body being capable of something so powerful.

Last night I watched my blood be pulled out of me, its yellow plasma separated, and then my blood pumped back into me. In less than an hour, 650 milliliters of my "golden" plasma filled a bag. It was a rather painless process. I'll admit I did not watch the needle go into my arm. But the brief physical discomfort I felt was a small price to pay for the potential payoff. My plasma could help save the lives of four people.

We're far from a vaccine for COVID-19, but by now you've likely heard about this experimental treatment that is helping some of the most severely ill. Convalescent plasma was first used to combat the Spanish Flu in 1918. The concept is rather simple, and the science is fascinating -- taking antibodies from someone who has recovered from a virus and giving them to a person who's struggling to fight it.

Isolated at home, the idea that contracting this virus would allow me to do some good in this world gave me a light to focus on at the end of a dark tunnel. I was determined to find a way to donate.

Road blocks

Three weeks ago I started calling hospitals and blood banks in the Los Angeles area. Every day the death toll is rising. People are in desperate need of help. I figured they would be thrilled hear from me.

"I believe I'm a very eligible donor," I'd say with all the enthusiasm you can imagine in my voice. "We aren't setup for that," they'd say. And then, "Go to the Red Cross website."

So I filled out the American Red Cross online donor request form, a very simple questionnaire asking if you were diagnosed with a COVID-19 lab test and the date of your last symptoms. And then I waited. Quarantined at home, I had nothing but time. A few days went by so I filled out the form again. The system is new. Maybe my request got lost in the shuffle?

I kept looking for the pothole I figured I would step in that would eventually disqualify me from donating. There were calls online for donors, but it was difficult to find information on the qualifications to be one. It boiled down to: You need to 1) provide documentation of a positive COVID-19 test; 2) either be symptom-free for at least 14 days with a subsequent negative COVID-19 test, or symptom-free for 28 days; and 3) meet the standard requirements necessary to donate blood.

So that's it? That's how I save a life? I had my positive test result, so all I needed to do was wait? I don't know my blood type -- is that a problem? Now I hear there are these antibody tests. Do I need one to prove I've got them? There were so many questions I couldn't get answered.

I was frustrated. That feeling of helplessness was growing more painful. And then last Sunday, Day 30 of being symptom-free, a woman with a kind voice called me from the Red Cross.

"I'm with the plasma department," she said. I had tears in my eyes before I even got her name. Finally, I could be a part of the solution.

Donation day

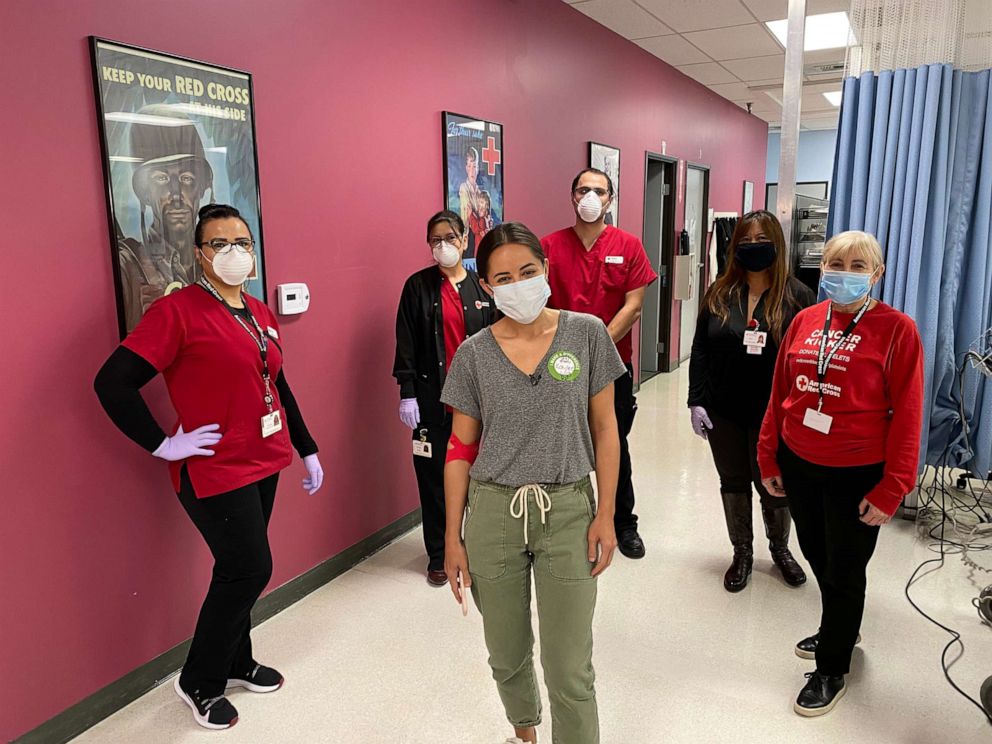

The check-in process was quick and easy. A temperature check of my forehead. A simple health screening proceeded, as is standard protocol for all blood donations. Then all of a sudden, I'm in a large reclining chair and the crease of my right arm is being swabbed with alcohol. For all the waiting, all the anticipation, all the time spent going in circles on the phone, things were suddenly unfolding so fast.

I didn't know how to process my feelings in the moment. When I got the fateful call to schedule my appointment to donate, I burst into tears. With that release, I thought I'd gotten all the tears out. I was wrong.

During the donation process, I could see the bag filling up with my blood, and then draining as it came back into me. That is just as strange to see as it sounds. But it wasn't until the process was complete that my lovely nurse, Gabriela, showed me the bag of my plasma. The tears were impossible to hold back.

It took me back to March 1, the day I saw the first ambulances with their red flashing lights pull up to Life Care Center of Kirkland, Washington. Every day for the next week I would see them come back. And then I would meet someone who had just lost a loved one. Like Mike Weatherill, who suddenly lost his mother Louise. Could this treatment have helped her? Or any of the 37 people who died at Life Care?

Doctors stress this treatment is experimental. They say the stories of success are hopeful, but anecdotal. Well just ask Connie Griffin how she gained the strength to fight for her life on a ventilator. On a Zoom call from her hospital bed, she didn't hesitate to tell me she believes the plasma donation she received at Miami Valley Hospital in Dayton, Ohio, saved her life.

Donation centers are struggling to meet the demand for this valuable product. Because of the lack of testing in this country, very few people are qualified to donate. The Red Cross says 30,000 have filled out that same online form I did, but only 2-3% of people are eligible. You must have a positive COVID-19 test, not presumptive positive. But that's about to change. The Red Cross will soon use antibody tests to identify potential donors of convalescent plasma, dramatically increasing that donor pool.

Even though I don't know who will receive my donation, to those families I say: I've never felt such a privilege as to be able to give you the gift of hope.

This report was featured in the Tuesday, April 21, 2020, episode of “Start Here,” ABC News’ daily news podcast.

"Start Here" offers a straightforward look at the day's top stories in 20 minutes. Listen for free every weekday on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, the ABC News app or wherever you get your podcasts.

What to know about the coronavirus:

- How it started and how to protect yourself: Coronavirus explained

- What to do if you have symptoms: Coronavirus symptoms

- Tracking the spread in the U.S. and worldwide: Coronavirus map

Tune into ABC at 1 p.m. ET and ABC News Live at 4 p.m. ET every weekday for special coverage of the novel coronavirus with the full ABC News team, including the latest news, context and analysis.