To study coronavirus in the air, all eyes on a Chinese restaurant

U.S. says virus generally is spread by droplets.

A new study of a COVID-19 outbreak tied to a restaurant in China is re-igniting questions about how far the novel coronavirus could spread in the air and how airflow through ventilators or air conditioners, and the air quality itself, could play a role.

The World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have long maintained that the virus is spread primarily through droplets in person-to-person contact and in some cases from contaminated surfaces like stethoscopes, and rarely travels more than six feet in the air. But the recent study, conducted by the Guangzhou Center for Disease Control, suggests that the virus not only passes through person-to-person spread at close range, but can travel farther with help from air currents blowing from ventilation systems.

A second study of the same restaurant, this one using a simulation and led by researchers from the University of Hong Kong, concluded that crowded gatherings and "poor ventilation" with little outside air brought into the room created an isolated loop, allowing virus particles to be transferred from table to table.

Tune into ABC at 1 p.m. ET and ABC News Live at 4 p.m. ET every weekday for special coverage of the novel coronavirus with the full ABC News team, including the latest news, context and analysis.

Infectious disease aerobiologist Dr. Donald Milton of the University of Maryland described the initial Chinese study as “solid and very useful” and said the conclusions are worrisome and worthy of further investigation as American restaurants and other buildings look to re-open their doors.

“It does point to the virus being able to survive in air for a while and travel a little bit farther,” Milton told ABC News, echoing several other experts with whom ABC News spoke. "If there's a good ventilation system, you're not going to get enough exposure to be infected. If there isn't good ventilation, then the data suggests that it's crowded, poorly ventilated places where there have been outbreaks."

An early release of the Guangzhou study, set to be published in a U.S. CDC journal, Emerging Infectious Diseases, in July, focused on 10 coronavirus cases that were traced back to a restaurant in Guangzhou, China, just north of Hong Kong and 600 miles away from Wuhan, the original epicenter of the outbreak.

Wuhan closed its borders and enforced a lock-down on the city of 11 million on Jan. 23. That same day, the “index case patient," a 63-year-old woman, and her family traveled from Wuhan to Guangzhou, according to the Chinese study.

The following day, their party was seated for lunch on the windowless third-floor dining room of the restaurant as two other families dined at tables that were set close, but not too close, the study said. Later that day, the index patient developed a fever and cough and went to the hospital. Less than two weeks later, nine other diners were infected -- five of them had been seated at separate tables and were not part of the index patient’s family.

Researchers determined that the virus was likely transmitted to the other families at this restaurant by droplets of the virus that were pushed through the air by air-conditioned ventilation. Some of the farthest infected persons were 4.5 meters from the index patient -- a nearly 14-foot distance, more than double the commonly held 6-foot social distancing guidelines.

The Guangzhou study acknowledges the limitations of its work, including the lack of attempts to simulate the ventilation system’s airflow. But the authors ultimately recommended that in order to prevent the spread of the virus in restaurants, establishments should “increas[e] the distancing between tables and improving ventilation.”

The other new study, this one from researchers at the University of Hong Kong, took a second look at the restaurant and its ventilation system. For its report, which also has yet to be peer-reviewed, the researchers brought in mannequins and used tracer gas in a simulation of the restaurant to study the airflow as they suspect it was during the Jan. 24 lunch.

That team concluded that it was the density of the crowd and poor ventilation that most likely caused the outbreak in the restaurant.

Dr. Todd Ellerin, the director of infectious diseases at South Shore Health in Massachusetts, said the Chinese study is noteworthy, but not enough is currently known to go as far as reclassifying the coronavirus as primarily featuring "airborne" transmission versus droplet transmission, which is still believed to be the main way the virus spreads from person to person.

“Then we would have to reclassify this virus as an airborne virus, like the measles, like the chickenpox, and that would be very different," he said.

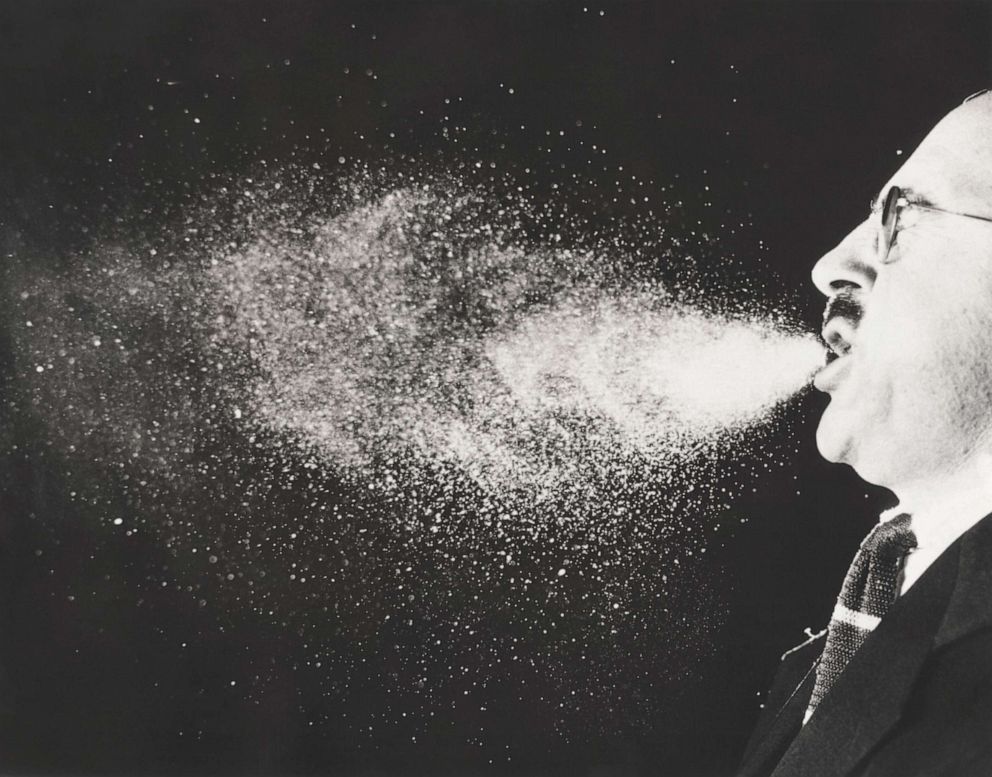

According to a 2009 World Health Organization report, when a person coughs, they can spray up to 3,000 droplets, and for a sneeze as many as 4,000. Larger droplets fall to the ground or on surfaces, creating fomites and, when touched by another person, could infect them. In order for droplets to remain suspended in the air, and be considered airborne, they need to be very small -- less than five micrometers and travel farther than one meter, or a little more than three feet.

The coronavirus is "not behaving like an airborne virus, but that doesn’t rule out the possibility of airborne transmission in certain circumstances," Ellerin said.

The World Health Organization has repeatedly said that the coronavirus is "NOT airborne," and says it is "mainly transmitted through droplets." In late March the group said that an analysis of more than 75,000 cases in China found "airborne transmission was not reported."

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has taken a similar position. “Airborne transmission from person-to-person over long distances is unlikely,” the government agency's website says. And medical experts cite the lack of evidence and documentation that virus droplets can float in the air in real-life scenarios.

It’s unclear how long coronavirus-infected droplets remain in the air, but another recent Chinese study to be published in the journal Nature found that adequate ventilation dramatically reduced floating virus particles. The study, conducted at two Wuhan hospitals, found higher concentration of those particles in places with high foot traffic and in bathrooms that were not ventilated.

A Tulane School of Medicine research team specializing in infectious disease aerobiology recently studied COVID-19 in aerosol form and concluded that in a controlled laboratory setting, the virus maintained its ability to cause infection even after 16 hours in the air.

“There is a growing body of evidence that people can be infected by airborne transmission,” Dr. Chad Roy, one of the authors of the study, told ABC News.

Milton told ABC News that while there is specific scientific criteria to classify a virus as being airborne -- which coronavirus is not currently -- the suspicion that it could travel farther in the air than currently known in the real world, depending on the ventilation in the room, is concerning enough.

Kevin Van Den Wymelenberg, who runs an institute at the University of Oregon focused on creating buildings supportive of human health, said that while the U.S. looks to reopen the economy, people need to apply similar thinking and planning as they reopen buildings, from increasing air exchange rates within commercial buildings so more outside, fresh air is pumped in, to simply opening a window and accessing sunlight.

In the future, he says technology will play a key role in making building safer, with enhanced filtration systems and real-time monitoring for airborne microbes.

Diluting indoor air is key, said Van Den Wymelenberg, because it affects the concentration of potential viruses in the air, as the minimum infective dose of the aerosolized virus is still unknown.

“It is very difficult to entirely avoid aerosolized exposure, but you can increase air exchange rate and the degree to which you are filtering air, but there is no perfect system," he said, adding that unfortunately, it is very common within commercial buildings for indoor air to be recirculated.

There are approximately 600,000 restaurants in the U.S. The industry’s trade group, the National Restaurant Association, told ABC News they are aware of the Chinese study but are following U.S. CDC recommendations. They provided a 10-page “reopening guidance” book that is sent to all their members. It does not mention ventilation or air quality concerns.

Roy said he thinks indoor places like restaurants should take the possibility of viral spread propelled by airflow seriously.

“Yes, it is possible,” said Dr. Roy. “It’s my hope that leadership will consider this study."

Milton agreed, and also encouraged public health officials to begin addressing the concern.

“There’s a lot we can do to prevent it and in many ways there’s much more we can do than just hand washing," he said. "Rather than be afraid of this we need to be open about it, talk about it, and get over the fear and help people understand."

Dr. Jay Bhatt is a practicing internist, an Aspen Health Innovator Fellow and an ABC News contributor.

Editor's Note: This article has been changed to note that Emerging Infectious Diseases does not post or publish articles that have not been peer-reviewed. The article COVID-19 Outbreak Associated with Air Conditioning in Restaurant, Guangzhou, China, 2020 will be published in July. A disclaimer on the early release says: "Early release articles are not considered as final versions. Any changes will be reflected in the online version in the month the article is officially released."

Jay Bhatt, a practicing internist and Aspen Health Innovators Fellow, is an ABC News contributor.

What to know about coronavirus:

- How it started and how to protect yourself: Coronavirus explained

- What to do if you have symptoms: Coronavirus symptoms

- Tracking the spread in the U.S. and worldwide: Coronavirus map