What it's like being undocumented during the novel coronavirus

“Being undocumented is just – it's hard. It's real hard."

Just like everyone else, Cleyvi, 24, has had to tell her children that life during the age of the novel coronavirus pandemic just isn’t the same.

“Every kid wants to go out to the park, to McDonald’s,” she told ABC News. “And I just told him we can’t right now.”

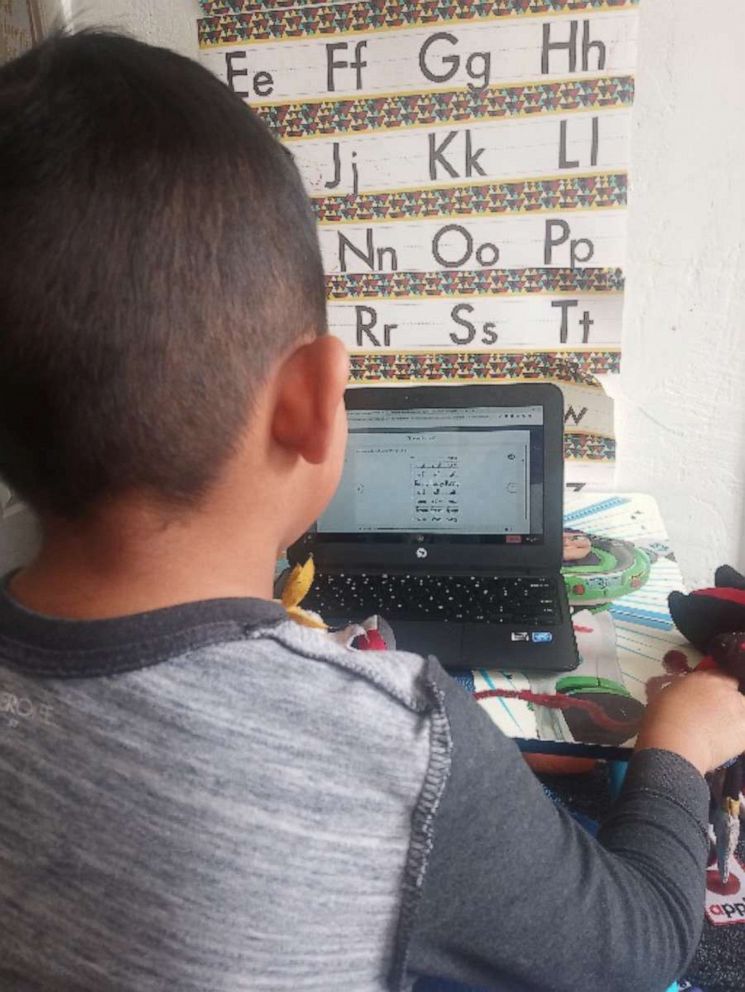

Cleyvi, whose last name ABC News is withholding because she fears reprisal from the authorities, lives with her husband and three young sons – ages 5, 3 and 1 – in Los Angeles. She said her eldest child understands the basics of the novel coronavirus: that it can give people fevers and affect the way people breathe.

“He knows he has to wash his hands every time he touches something, every time he wants to eat, after eating,” Cleyvi said. But for her, “the biggest stress” is figuring out how to pay the bills: rent, electricity, cable, food, diapers, formula and potentially medical expenses.

While the coronavirus has smothered the U.S. economy and families across the nation are learning to deal with isolation, a loss of income, and in some cases grief, the virus has hit Cleyvi's family harder than most. She and her husband are both undocumented, even as their three children are U.S. citizens.

Tune into ABC at 1 p.m. ET and ABC News Live at 4 p.m. ET every weekday for special coverage of the novel coronavirus with the full ABC News team, including the latest news, context and analysis.

Despite experiencing the same economic downturn, undocumented immigrants – and even immigrants with tax identification cards – will not be receiving the same federal help as many Americans, such as the economic impact payment, which is up to $1,200 for an individual or $2,400 for a married couple, plus $500 for each child. Undocumented immigrants also do not qualify for unemployment, which has been expanded and extended due to the crisis.

Roughly 10.5 million unauthorized immigrants live in the United States, and before the coronavirus financial crisis they made up roughly 4.6% of the labor force, according Pew Research Center.

“What causes the most difficulty for them is that they’re also experiencing loss of income, but without the subsidized support that is being offered,” said Michelle Rhone-Collins, CEO of LIFT, an organization that helps lift families out of poverty using both financial and holistic approaches. “Their voices aren’t even part of the conversation.”

While Cleyvi's family has been doing their best to save and come up with contingency plans, they’re worried. She told ABC News she wonders about what will happen if one of them gets sick and must self-isolate. Will they have enough to pay the bills, and enough left over to buy diapers and formula? And what about the possibility of authorities coming and knocking on their door?

“This is traumatic,” said Rhone-Collins. “It is traumatic for a group that already is experiencing – and already has experienced – heightened trauma.”

The impact of the COVID-19 financial crisis

The outbreak of COVID-19 caused a significant decline in the U.S. economy -- with thousands of "non-essential" businesses closing around the country in a matter of days to facilitate stay-at-home orders and other social distancing measures. According to an analysis done by the federal reserve bank of St. Louis, as many as 47 million workers could be laid off – potentially making the unemployment rate a staggering 32.1%. But this does not include the number or rate of undocumented immigrants who have also been laid off.

Cleyvi's husband works in plumbing, but since the coronavirus crisis began, most of his clients have cancelled home visits and appointments and his family’s source of income is running dry. Cleyvi spends her days raising her three children, and her nights taking online classes getting her high school diploma through the Los Angeles Public Library program.

“The jobs that our members were working primarily in are hospitality and in education and healthcare, and also within the restaurant and hotel industries,” said Rhone-Collins. “So yeah, they’re not working.”

According to Department of Labor data, the service industry – including accommodation and food services – was among the hardest-hit by the impact of the coronavirus. Manufacturing, retail, and construction have also been heavily affected as well.

LIFT provides help to nearly 1,000 low-income families across the United States in cities like Los Angeles, Chicago, Washington, D.C., and New York – roughly 30% of which are undocumented, according to Rhode-Collins. Cleyvi's family is one of them.

When the crisis was beginning to pick up, already 70% percent of LIFT members had lost their jobs. Now, nearly 90% of LIFT families have reported a significant loss of income. LIFT has been able to provide $500 to many of its families and is hoping to provide more relief soon.

But $500, without any additional government relief, is not enough for a family of five. Cleyvi said to cover the cost of living – including paying rent, the electricity bill, and food – her family would need at least $1,000. Because her children are citizens, she has been approved for food stamps, but she's concerned this may not cover all her family's needs.

“I don’t know that people are really aware that there are a lot of people that are left out that are also contributors to our economy,” Rhone-Collins said. “And the strength of our economy is only as good as those who are at the edges of it.”

The CARES ACT, the $2.2 trillion bill signed into law in March, will be providing Americans with unprecedented relief during this crisis. Many will receive a $1,200 deposit or check, and small businesses can apply for loans – which essentially become grants – if no employees are laid off. But this does not apply to the millions of undocumented immigrants who live in the United States, even if they’ve lived here for most of their lives.

Cleyvi has been living in the United States for almost 20 years – she was brought to the U.S. from Mexico when she was five. She said she even tried applying for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) when she was younger, but her family couldn’t afford the application process because she grew up in a single-parent, single-earner household.

“It’s unearthing the inequality that was already there,” Rhone-Collins said of the coronavirus, saying most of LIFT's members were already living paycheck to paycheck before the crisis began. “I think that the people who are going to feel the impact of the economic downturn the most are the ones who have already been in the hole. And the reason that they are in the hole is because of a lot of systemic barriers built into the way that our policies operate that don’t help them in productive ways.”

The extra toll of being undocumented

For Cleyvi's family, a simple task for many – like picking up groceries or finding diapers – can be exhausting. Cleyvi, unable to find certain supplies at local markets, tried recently to go to Costco. But Costco requires a valid government-issued identification card.

“This is our only option – to come to regular markets,” said Cleyvi. “We can’t really go to big places like those. So that’s hard to be running around to different markets to see if we find certain things.”

But Cleyvi says they have the essentials to try and keep everyone safe.

But some children are not so lucky.

As of April 2, five unaccompanied undocumented children in federal custody in two facilities in New York were declared either presumptive positive or are confirmed to have the coronavirus, according to the Department of Health and Human Services.

HHS has temporarily stopped putting unaccompanied minors into facilities in New York, California and Washington, which are coronavirus hot spots. There are over 3,000 unaccompanied undocumented children in the care of custody of the Office of Refugee Resettlement.

When ABC News reached out for comment, HHS responded saying "the situation remains extremely fluid and can change rapidly."

There are at least eight detention center facilities across the United States, four of which are government operated, that have reported cases of COVID-19, according to Freedom for Immigrants.

But despite the severe loss for many, Rhone-Collins believes this is a moment to be “less exclusionary” and include the “people who need it the most.”

“We do not have to continue to plan in a way that increases the racial wealth gap,” she said. “This is an opportunity for us to close it by doing what’s right and that's by holding the people who are most vulnerable at the center, not at the edges and fringes.”

“I think that with COVID, the hope and the opportunity is to actually learn around how a response can be quick,” she later continued. “It can be empathetic. It can be simple. It can make sense.”

Cleyvi has noticed in her "Mommy and Me" classes that other mothers are facing similar issues. Rather than hoarding their own supplies, her community has come together to share resources – whether that be formula for their babies, vegetables, diapers, or cleaning supplies.

“I know we aren’t the only family struggling right now,” she said.

What to know about coronavirus:

- How it started and how to protect yourself: coronavirus explained

- What to do if you have symptoms: coronavirus symptoms

- Tracking the spread in the US and Worldwide: coronavirus map