US fighting vaccine shortage, but ramping up manufacturing not easy, experts say

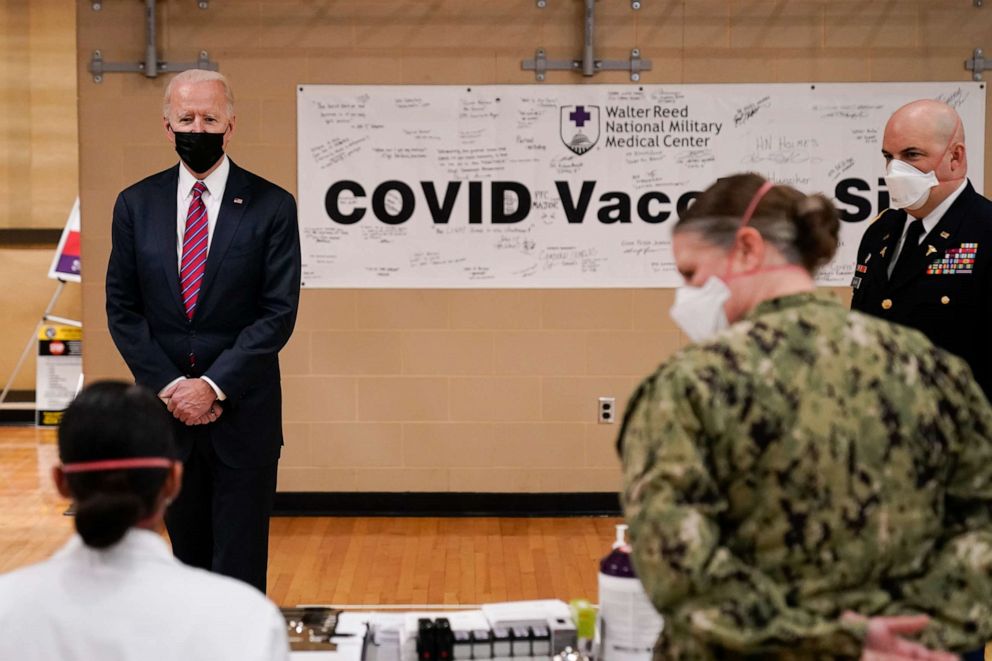

The Biden administration is working to produce more vaccines at a faster pace.

When President Joe Biden took office this month, ramping up the available supply of COVID-19 vaccines became one of his administration's top priorities.

The Biden administration's mission: to find a way to produce even more vaccine doses at a faster pace, exceeding the quantity and timescale promised by pharmaceutical companies Pfizer and Moderna as part of their contracts with the U.S. government.

But experts say it will not be so easy. A vaccine is not a steel part, it is a complex biomedical product.

"We're actually dealing with living organisms here," said Cody Powers, a principal at ZS Associates, a professional services firm that works with companies to help develop and deliver medical products. It's "different from making simple consumer goods that maybe you can put together a manufacturing line faster."

Both Pfizer and Moderna use new vaccine technology: messenger RNA, or mRNA. RNA is particularly fragile, making it essential for the drugmakers to handle the process scrupulously and meticulously to maintain their quality control and ensure safety.

"To actually produce what's in the vaccine, whether it's a reagent, whether it's an antigen, or in the case of the Pfizer and Moderna, the mRNA, you have to produce that part of it, and then you have to harvest it, and then you have to produce the encapsulation," said Dr. Bruce Y. Lee, Executive Director of Public Health Informatics, Computational, and Operations Research, and professor of health policy and management at the City University of New York.

Each of these steps requires specific equipment, as well as the right personnel to do it, he said, adding, "You can't necessarily always take one person from doing one aspect of a product line switching them over."

There are also elaborate procedures to be followed to ensure that all the manufacturing requirements and safety protocols have been met, and factories are subject to regular audits from the Food and Drug Administration. And the consequence of sending a spoiled batch out to be injected into people's arms would be catastrophic, experts cautioned.

"Much time, energy, attention and resources are required to make sure that the process meets all the requirements to be able to produce in a responsible fashion," noted Powers, saying public trust in vaccines is fragile.

Meanwhile, there's also a learning curve, experts said. It's the first time this type of vaccine has been manufactured on such a massive commercial scale. Thus, "we don't know everything there is to know yet," about these new vaccines and technologies, added Powers.

Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla said in an interview with Bloomberg on Tuesday that the company would be able to supply the U.S. with 200 million COVID-19 vaccine doses by the end of May, two months sooner than previously expected.

Moderna's Chief Executive Officer Stéphane Bancel also said last month during a Nasdaq Investor Conference that he felt "very comfortable" that the company would be able to produce 500 million doses of its COVID-19 vaccine in 2021.

Johnson & Johnson, which is expected to apply for an emergency use authorization in the coming weeks, said Tuesday that it is on track to deliver 100 million coronavirus vaccine doses to the U.S. by the end of June.

But even if factories owned by Pfizer and Moderna -- the only two vaccines currently authorized in the U.S. -- are running at maximum capacity, there might be other ways to boost supply, experts said. A third company could volunteer, offering up a factory with the right equipment to handle the task.

One example of such collaboration is that of French drugmaker Sanofi's deal with its rivals, Pfizer and BioNTech, to produce over 100 million doses of their mRNA vaccine for the European Union at Sanofi's site in Frankfurt, Germany.

This uncommon pact could encourage other pharmaceutical firms to cooperate with companies developing effective vaccines, Lee said.

But factories with this level of technical capacity are in short supply, and they would need to stop manufacturing other lifesaving medicines to prioritize mRNA vaccines.

Vaccine makers rarely dedicate everything to one product, Lee explained. "They are also producing products that generate revenues for them," Lee said.

Still, experts said there might be other, smaller ways the Biden administration can help boost manufacturing supply. The administration should evaluate the entire vaccine supply chain as quickly as possible, to see where the vaccines are actually getting hung up, Lee said.

"You don't just run out to the football field without planning and really seeing what's the situation first. If you're trying to adjust on the fly, you may not know the deeper issue," he said.

Within its first week, the administration quickly zeroed-in on one key issue: syringes. The FDA has authorized medical workers to extract extra doses from Pfizer vials, but to utilize all the available supply from those vials, more precise, specialized syringes are needed.

More people can be vaccinated if we make better use of the supply that is already being manufactured, Powers said.

White House press secretary Jen Psaki discussed at her first briefing using the Defense Production Act, a Cold War-era law that gives the government certain control over private industry, to manufacture these syringes, but the Biden administration has not been specific on any companies that might be actually doing this.

Meanwhile, the administration could help companies secure much-needed raw materials and chemical ingredients -- an ongoing challenge, particularly given that the pandemic is a global crisis, with many nations competing for the same supplies.

"It's a global economy and we don't have the capability to provide everything we need on our shores," said Erin Fox, senior director of Drug Information and Support Services at University of Utah Health. Securing more raw ingredients could become a key diplomatic goal for the Biden administration.

But ultimately, only the companies themselves can say exactly what would be helpful to boost supply. And the pharmaceutical industry is famously guarded, said Fox.

"We actually don't know if we just have to trust the companies to tell us what they might need because they have no obligation to be transparent," Fox said.

As of Friday, 49.2 million vaccine doses had been distributed by the federal government to states and other jurisdictions, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Of that amount, 27.8 million doses -- approximately 56.7% -- have been administered.

Moderna and Pfizer have agreed to supply the federal government with 200 million doses, by the summer, enough for 100 million Americans. Johnson & Johnson, which is expected to apply for an emergency use authorization in the coming weeks, said Tuesday that it is on track to deliver 100 million coronavirus vaccine doses to the U.S. by the end of June.