Vitamin D deficiency unlikely to fully explain COVID-19's effect on people of color

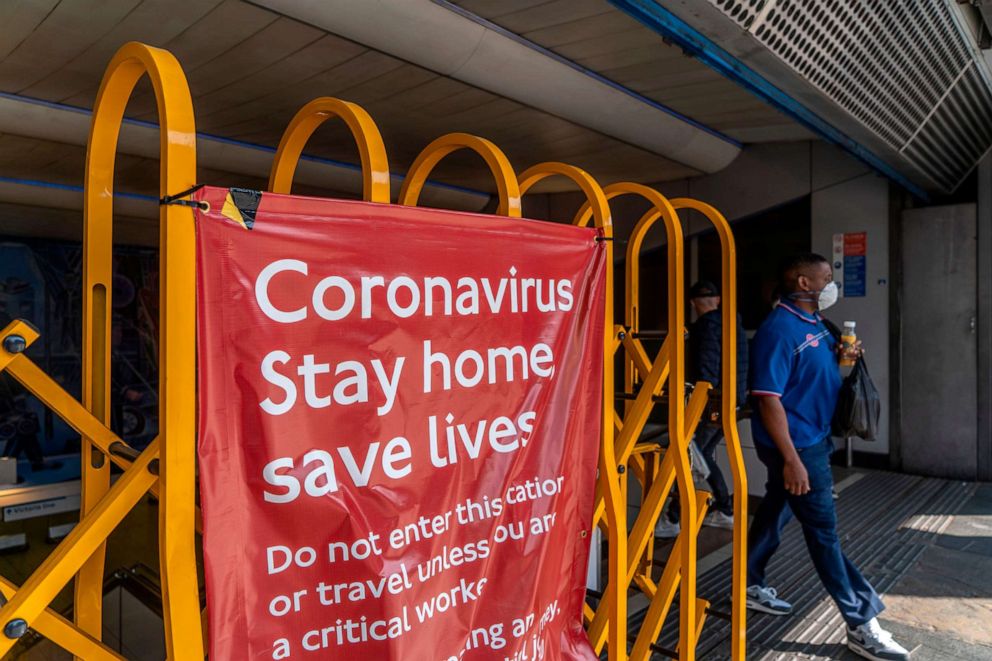

Almost every doctor who died from COVID-19 in the U.K. was a person of color.

Public health officials in the United Kingdom have launched an urgent review into the potential role of vitamin D in protecting people against the coronavirus, exploring whether vitamin D deficiency could help explain why Black and Asian citizens are more likely to die of the virus.

This review comes in the wake of an alarming revelation that 94% of the doctors who have died from COVID 19 in the UK were Black, Asian and from other minority ethnic groups.

"These figures are extremely disturbing," said Dr. Chaand Nagpaul, chair of the British Medical Association, to the BBC. "This is a figure that cannot be explained on pure statistical variation," he said.

Experts agree that it's bad for your immune system to have low levels of vitamin D, some point to limited evidence that such a deficiency could make it harder to recover from lung infections.

People with darker skin may need more sunlight to get the recommended levels of vitamin D than people with lighter skin, prompting the theory that Black and Asian British citizens may not be getting enough vitamin D, in turn making them more vulnerable to COVID-19.

However, experts caution that this is just a theory, and would need to be supported with high-quality evidence, preferably from a randomized clinical trial designed specifically to answer this question.

And they point out that vitamin D deficiency alone is unlikely to explain the stark disparities between different racial and ethnic groups when it comes to COVID-19.

"There are likely to be many different reasons Black or Asian people are more likely to suffer from COVID-19 infection," said pharmacologist Andrew Hill, MD, of the University of Liverpool, in England, who is not involved in the urgent review.

"More densely populated housing, higher prevalence of diabetes and hypertension, more likely to use public transport and also potentially low Vitamin D levels," Hill said. "I doubt that Vitamin D deficiency is the only reason for the higher risks of COVID-19 infection."

Nevertheless, the UK government is exploring to what extent -- if any -- vitamin D might play a role in lung infections among the health of its minority citizens.

In general, "it has long been known that vitamin D promotes good immunity," said Dr. Len Horovitz, pulmonary specialist at Lenox Hill Hospital, in New York.

However, studies have yet to prove that taking a supplement will help, according to Dr. Carlos del Rio, professor of medicine and global health at Emory University, in Atlanta.

"There are a lot of diseases in which worse outcomes are associated with vitamin D deficiency, yet almost none has shown that restoring vitamin D leads to improved outcomes," del Rio said. "Bottom line, association does not mean causation," he said.

And when it comes to COVID-19 specifically, experts agree data is inconclusive.

Dr. Beth Kitchin, from the University of Alabama-Birmingham's Department of Nutrition Sciences, said that although several studies have suggested a link between vitamin D deficiency and coronavirus infection and COVID-19 severity, these studies so far have all been observational, meaning that there may actually be no link at all.

Dr. Todd Ellerin, director of infectious diseases at South Shore Health, in Massachusetts, explains that in a number of studies, the apparent correlation between low vitamin D and worse COVID-19 outcomes disappears once researchers adjust for other factors that can also affect COVID-19 risk such as age, weight and socioeconomic deprivation.

Such findings "do not support ... that vitamin D concentration may explain ethnic differences in COVID-19 infection," reported one such study that uses data from the UK Biobank, a resource that collects health data on half a million people from the UK.

"It remains to be investigated properly, through randomized controlled trials, whether vitamin D can actually help prevent COVID-19 infection, or prevent severe illness," said Ellerin.

For now, a spokesperson for Public Health England said the government will be collecting and reviewing existing evidence on vitamin D and the risk of acute respiratory tract infections, taking into consideration evidence on Black, Asian and other ethnic groups where available.

The UK's regulatory agency, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), will publish a review on vitamin D sometime next week, with the help of Public Health England.

However, experts stressed that relying on existing studies might not help answer this question, because existing studies skew heavily toward "observational" studies rather than the scientific gold-standard of randomized clinical trials.

"Right now, no one can answer the question: Does vitamin D prevent severe COVID-19?" said Dr. Vincent Racaniello, of the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at Columbia University, in New York.

On June 18, the British Medical Association demanded more "tangible and urgent action" from the government to address the effects of COVID-19 on the country's minority communities. The association called for "immediate timelines for action plans instead of further consultations and reviews".

Although a "theoretical possibility," it remains unclear whether vitamin D can protect against coronavirus infection, said Ellerin. Experts advise that if you have a specific vitamin deficiency, it is probably a good idea to talk to your doctor about possible ways to bolster your vitamin D intake.

However, experts caution that for people who already get enough vitamin D from their food and from the sun, taking a supplement is unlikely to help — and may even be harmful if consumed in excess.

Hassal Lee, Neuroscience Ph.D. and student doctor at the University of Cambridge, U.K., is a contributor to the ABC News Medical Unit. Sony Salzman is the unit's coordinating producer.