Irish state makes landmark apology for church-run homes, where thousands of infants died

The homes for unmarried mothers saw moms forcibly separated from their children.

DUBLIN -- Ireland’s prime minister on Wednesday made a solemn state apology to the women and children that suffered in church-run homes for unmarried mothers and their babies, as the country confronts a landmark report documenting decades of abuse at the institutions, where thousands of infants reportedly died.

The report presents the findings of a public inquiry into the so-called Mother and Baby Homes that during the 20th Century, generations of unmarried women in Ireland were forced into after becoming pregnant and then often forcibly separated from their children.

The report, published on Tuesday, and the apologies were presented as a moment of national reckoning and atonement for an extraordinarily dark piece of Ireland’s history, one that again forces it to grapple with the role of the Catholic Church.

“On behalf of the Government, the State and its citizens, I apologize for the profound generational wrong visited upon Irish mothers and their children who ended up in a Mother and Baby Home or a County Home," Prime Minister Micheál Martin said during a speech to Ireland’s parliament the Dáil on Wednesday.

“We had a completely warped attitude to sexuality and intimacy, and young mothers and their sons and daughters were forced to pay a terrible price for that dysfunction," Martin said. “As the Commission says plainly – ‘they should not have been there.’”

The Catholic Church in Ireland and some of the religious orders that ran the homes, also issued apologies in response to the report. Archbishop Eamon Martin, the leader of the Church in Ireland, on Tuesday said he “unreservedly” apologized to survivors.

The report from the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes, which runs around 3,000 pages, provides a detailed anatomy of institutions—bleak, usually gated places where life was strictly regimented and often resembled a prison.

In testimonies, survivors describe intense stigma and callous treatment. Some women described being kidnapped and forcibly taken by their families to the homes.

The report found the homes featured an exceptionally high infant mortality rate, recording that 9,000 children died at 18 homes between 1922 and 1998. That was 15% of all the institutions' children, almost double the national rate of infant mortality.

Around 56,000 unmarried mothers and about 57,000 children were kept in the homes, according to the report, which said Ireland likely had the highest proportion of women admitted to such institutions in the world in the 20th Century.

It blamed the homes' existence on a toxic alignment between the Catholic Church, the state and an extremely conservative, misogynistic society.

Despite often being aware of the appalling death rates and conditions in the homes, the report said the Irish state did almost nothing to intervene. There was “little evidence that politicians or the public were concerned about these children,” the report said.

Martin acknowledged that, saying the state “failed you, mothers and children.”

Campaigners and survivors of the institutions described mixed feelings, though, with some saying the report failed to convey what they endured and warning it ignored some key issues such as forced adoption.

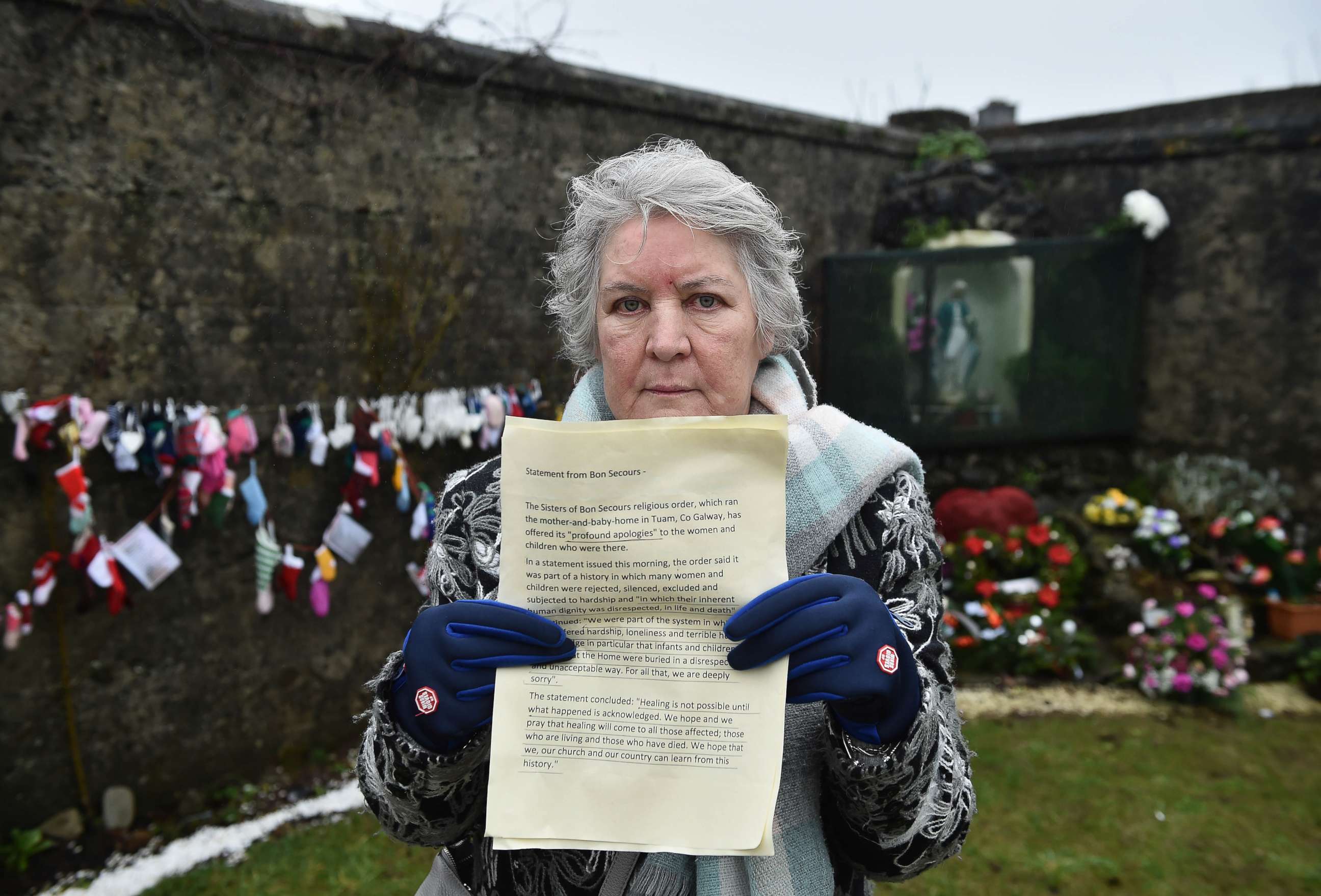

Catherine Corless, a local historian who helped first trigger an intense public examination of the homes' history, told Irish media on Tuesday she was “deflated” by the report and felt it let down survivors.

Corless, in 2014, uncovered death certificates for nearly 800 children who died at the former Bon Secours home in Tuam in western Ireland, but only found a burial record for just one child. Investigators then found a mass grave containing the remains of babies and young children in an underground sewage structure on the grounds of the home. The provoked horror in Ireland and around the world set off a national discussion that led to the report.

Martin held a webinar with Corless and other survivors on Tuesday ahead of his apology in parliament. Afterward, Corless and others said they had been upset by his comments.

“The survivors are well-used to the government making promises but what disturbed them mostly was that Micheál Martin put the blame back onto society,” Corless told the public broadcaster RTE.

While critical of the state and church, the report said the mistreatment of the women was fundamentally a product of a bigoted Irish society, where ordinary people cast out unmarried mothers and ‘illegitimate’ children.

“Responsibility for that harsh treatment rests mainly with the fathers of their children and their own immediate families,” an opening passage of the report reads. “It was supported by, contributed to, and condoned by, the institutions of the State and the Churches. However, it must be acknowledged that the institutions under investigation provided a refuge - a harsh refuge in some cases - when the families provided no refuge at all.”

Catherine Conolly, an opposition MP, heavily criticized the report, saying it was “incomprehensible” that it had concluded there was no evidence the church and state had forced women into the institutions.

“All the evidence given confirms this,” she told parliament. “I find the whole thing actually repulsive to tell you the truth.”

Although they appreciated the apology, several survivors said they wished it had come once they had had time to digest the huge report.

“It’s too early and too late,” Anna Corrigan, whose two brothers are believed to have died in Tuam, told The Irish Independent Tuesday. “The apology should actually wait until people have sight of the report and can settle.”

Martin pledged to fulfill the report’s recommendations and outlined a series of measures that would be taken to redress the victims, including financial compensation and access to medical care. The government said it would also bring legislation that would give survivors the right to access their records, including adoption records.

That is a key demand of survivors, many of whom don't know their relatives' fate or who their parents are.

“An apology on its own is not enough,” Martin told parliament. He noted how many former residents described feeling shame about their situation.

“The shame was not theirs,” Martin said. “It was ours. It remains our shame.”