'There is another Mexico now': Country's new president reflects on challenges ahead

"There is Another Mexico Now": Mexico's new president and the challenges ahead

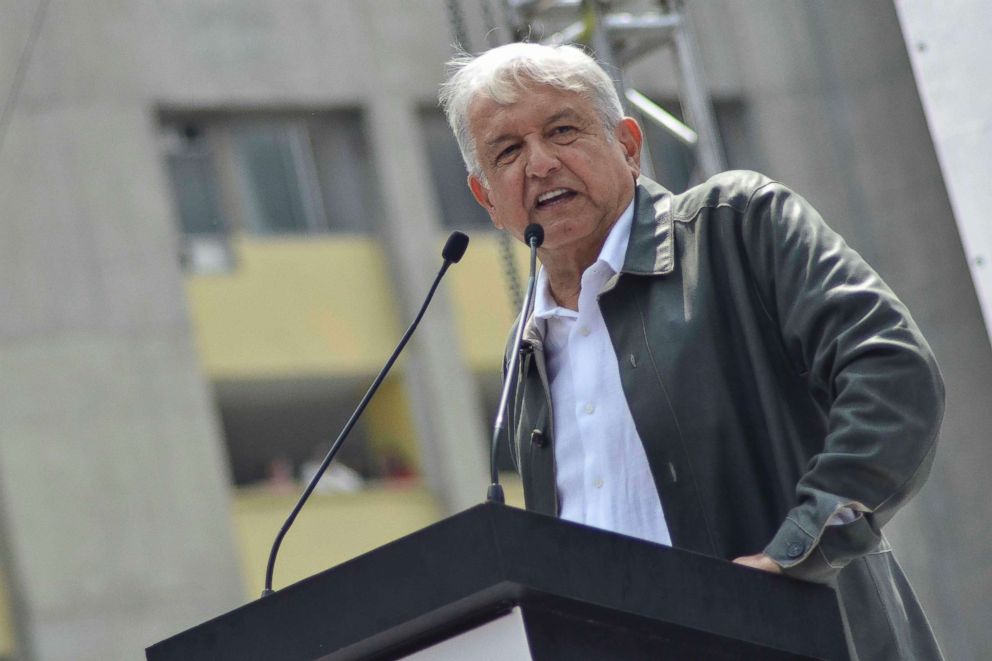

Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador, commonly known by the acronym AMLO, will take his seat as Mexico's new president on Saturday after winning the election with almost double the total number of votes of his closest rival.

AMLO, who has previously served as mayor of Mexico City, won with 53 percent of the votes, according to Mexico’s National Electoral Institute. He ran a campaign based on promises to return power to communities and fix the problems of corruption and violence that have resulted from the control of criminal organizations in the region.

But as time draws closer for Lopez Obrador to assume office, submitting proposals for legislation and readying the ground to fulfill his promises, the beloved president-elect has drawn criticisms and concerns on his approach to governance as he prepares to bring change to Mexico.

Road to the presidency

The eldest child of a merchant family, Lopez Obrador was born in Mexico’s southern state of Tabasco. He has spent 40 years navigating Mexico’s political landscape, starting as a member of Mexico’s ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) before joining the centrist Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD).

Lopez Obrador then became mayor of Mexico City in 2000. During his five years in office, he expanded social programs, built a new public university, cut salaries of city officials and provided financial support to the elderly, as well as single mothers, unemployed people and disabled citizens, garnering him the support of the poor and working class.

Lopez Obrador hoped to bring such changes to a national level, running for president in 2006 with a promise to prioritize the poor. But those very promises cost him the election, with his opponents saying AMLO would become Mexico’s Hugo Chavez, the late Venezuelan leader who helped lead his nation to economic crisis by running a presidential campaign on similar promises.

He tried again in Mexico’s 2012 presidential race. Again, he lost.

But then, Lopez Obrador decided to take a different approach. He started his own left-wing political party, the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA), scaling back in his populist views and switching his focus to anti-establishment, anti-corruption messages that promised to clean up the corruption and violent crime organizations that have been terrorizing the country.

This time, more than half of Mexico seemed to want the changes Lopez Obrador promised to bring to the country. On July 1, AMLO became Mexico’s president-elect.

Life as the president-elect

Since becoming Mexico’s president-elect, however, AMLO has become less confrontational. But all eyes are on what he will do once he is sworn in.

Andres Velasco, the dean of the school of public policy at the London School of Economics, said he believes that the future of democracy in Mexico could be an issue under Lopez Obrador’s ruling.

“Whether he’ll play by the rules of liberal policies or lean towards a more populist approach remains to be seen,” Velasco told ABC News.

During his campaign, AMLO promised he would get rid of Mexico’s presidential jet, which he said costs $392 million, and use the money towards social programs, a promise he seems to be keeping even after he was stranded in an Oaxaca airport back in October due to bad weather.

Simultaneously, Lopez Obrador’s administration announced plans to expand the Mayan train to the southern region of the country, saying that “it is of great importance to generate the wellbeing of the population of the south, promoting the development of the region, rebuilding the social fabric and reordering the territory.”

Mexican newspaper El Universal said that perhaps one of the greatest benefits of the project could be the creation of much needed jobs in the region, which struggles with poverty and inequality in most states.

Last month, AMLO canceled construction of a $13 billion new airport in Mexico City after an informal voting procedure with a small fraction of the population showed voters rejected the project, raising concerns that he will give in to his populist instincts once he becomes president, according to The New York Times.

But in an interview in June, Alfonso Romo, AMLO’s top economic adviser, told ABC News that AMLO “is not a populist.”

Instead, Romo said Lopez Obrador was a “very honest man” who understands “exactly the needs of the people,” running a government focused on fixing the country’s security issues, corruption and furthering its economic growth.

The escalating problem of violence

Since 2006, violence between criminal organizations and government forces in Mexico has escalated. Between 80,000 and 100,000 people have died in the country as a result of organized crime violence, according an analysis by the Council of Foreign Relations.

Lopez Obrador has promised to prioritize decreasing violence in Mexico during his presidency. He has proposed creating a new national guard, made up of both military personnel and national police forces, that will tackle the problem of violence in the country. But the move that has raised concerns about the further militarization of the country leading to a possible increase in violence.

“It is worrying that the president-elect has submitted a security proposal that essentially imitates the failed militarised security model and has allowed serious human rights violations to be committed by the armed forces,” Erika Guevara Rosas, Americas Director at Amnesty International, wrote in a statement.

Carlos A. Perez Ricart, a postdoctoral fellow in contemporary history and public policy at the University of Oxford, told ABC News that, given the circumstances, Lopez Obrador’s approach is still the best for Mexico.

“Mexico is living through an enormous crisis,” Perez Ricart, who was born and raised in Mexico, said, adding that there have never been as many homicides in Mexico as now.

To tackle the crisis in Mexico, Perez Ricart said, AMLO only had two options: to improve training of local and state police, a process that could take years; or to take a risk and increase military forces in the country.

Lopez Obrador’s decision to risk democratic governance in the hopes that militarizing the country can once and for all stop the violence in Mexico can even be seen as courageous, Perez Ricart said.

“Honestly, from a security point of view, there is no other solution. Even though the risks it poses, this is not so black and white. It’s gray,” Perez Ricart said.

Others, however, are more skeptical.

“Creation of a powerful military force is a lot more of a gamble because so much of the violence has involved the military,” Claudio Lomnitz, professor of Anthropology at Columbia University who focuses on Mexico, told ABC News. He pointed out that thousands of those who have died in Mexico have been killed during military operations.

Lomnitz explained that Lopez Obrador’s faith in the military instead of the local police force comes from the corruption, at the state level and within local agencies, that plagues the country, a problem that exists because of a lack of supervisory control on such agencies.

But AMLO’s move to further militarize the country could be a sign that he is headed towards an authoritative presidency, raising concerns about a lack of health in checks and balances in the country.

Impact on US-Mexico relations

Perhaps one of the biggest challenges facing Lopez Obrador as he takes over Mexico’s presidency is the country’s relationship with its neighbor to the north, the United States.

Mexico’s current president, Enrique Peña Nieto, was criticized for his perceived subservience to the United States, and particularly for what has been seen as his failure to defend Mexico’s honor in the face of attacks and insults from President Donald Trump.

But Peña Nieto’s approach to his relationship with the United States, particularly with Trump, seemed to have been part of his strategy to guarantee the conclusion of the NAFTA trade deal on terms that benefited his nation, Halbert Jones, Director at the Rothermere American Institute at University of Oxford, told ABC News.

During his campaign, however, Lopez Obrador vowed to put President Trump “in his place.” Back in 2017, he gave a speech in New York criticizing America’s newest president, saying that “Trump and his advisers speak of the Mexicans the way Hitler and the Nazis referred to the Jews, just before undertaking the infamous persecution and the abominable extermination.”

But things have changed since Lopez Obrador became president-elect.

“Interestingly, the fierce crash that many expected between Trump and Lopez Obrador has so far not materialized,” Jones said, adding that perhaps the reason is that Trump apparently sees parallels between AMLO’s political success and his own.

Earlier this week, however, things almost took a turn.

As the migrant caravan of thousands of people makes its way towards the U.S.-Mexico border, the Washington Post reported Monday that Lopez Obrador’s incoming administration had agreed to allow asylum seekers to wait in Mexico while U.S. courts processed their asylum claims.

In a statement, Olga Sanchez Cordero, Mexico’s incoming interior minister, denied the allegations that there was such agreement, adding that the most important thing for AMLO’s elected government is the protection of human rights for Central American migrants who have entered Mexico, providing them with food, health care and stay.

But experts believe that Lopez Obrador will follow in the footsteps of his predecessor and seek to avoid conflict with the United States, a move that Jones calls sensible given the power imbalance between the two countries.

Lopez Obrador is likely to also carry on with the NAFTA agreement struck by Peña Nieto and Trump. Additionally, he will also facilitate the process of establishing Trump’s new USMCA plan, a trade deal among the United States, Canada and Mexico that will replace NAFTA.

“[Lopez Obrador] understands and knows the importance of binational trade, and he knows the importance of a good, solid framework to regulate the trade between the two countries,” Tony Payan, a Francoise and Edward Djerejian Fellow for Mexico Studies at Rice University’s Baker Institute, told ABC News.

"He knows he needs that investment if he is going to produce the 4 percent economic growth that he promised. That is twice as fast as Mexico has been growing for the last twenty years, so he is going to need NAFTA but he doesn’t want to spend the political capital doing so,” Payan said.

'There is another Mexico now'

Life for Mexico both domestically and in the international sphere could be drastically different were Lopez Obrador to deliver on the promises he ran his campaign on.

The markets, however, might not like where Lopez Obrador wants to take his country.

After AMLO said he would slash the $13 billion airport project, he posted a video to social media addressing the criticism. A book titled "Who’s in Charge Here?" was visibly next to the president-elect.

“There’s been a change in the country. We have to let some people know that there is another Mexico now,” Lopez Obrador said in the video.

The Financial Times reported that, with the video, AMLO “wanted to send the message that he answered only to the Mexican people, not the financial markets or investors who had been staggered by his decisions.”

After the announcement, the Mexican peso fell to its weakest point in five months.

Two weeks later, AMLO’s incoming administration proposed to limit the fees banks charge Mexicans on every day banking operations, leading Mexico’s main stock index to its worst single-day loss in seven years, according to Americas Quarterly.

The next day, Lopez Obrador told reporters that he was against the proposal, reassuring investors that he did not plan to change banking laws for at least three years after he assumes his presidential seat.

But Perez Ricart from the University of Oxford said that Lopez Obrador is a domestic politician whose biggest concern is meeting the needs of his country, and that international opinion holds little bearing on his decisions.

Expectations from the most vulnerable, those who feel forgotten and neglected by a Mexico filled with corruption and inequality of both economic resources and political power, are high. These voters have entrusted Lopez Obrador to bring on the change the country needs, to bring power back to them and make their country safe and prosperous.

But as with every new presidency, whether Lopez Obrador can deliver on those promises remains to be seen.

"If the government succeeds in bringing down crime and violence, it will go down as a historic presidency for the nation," Lomnitz said. "But if it fails, who knows what Mexico will be."

Lopez Obrador, however, believes he has the solution to Mexico’s long struggle against violence and corruption.

"Who is in charge? Isn’t it the people? Isn’t it citizens? Isn’t it democracy?" Lopez Obrador said in his Facebook video. "This is what we’re changing."