Remarkable fossil of 180-million-year-old 'sea monster' preserved its Jurassic-era blubber and skin

Scientists have identified a warm-blooded ‘fish- lizard' 180 million years old.

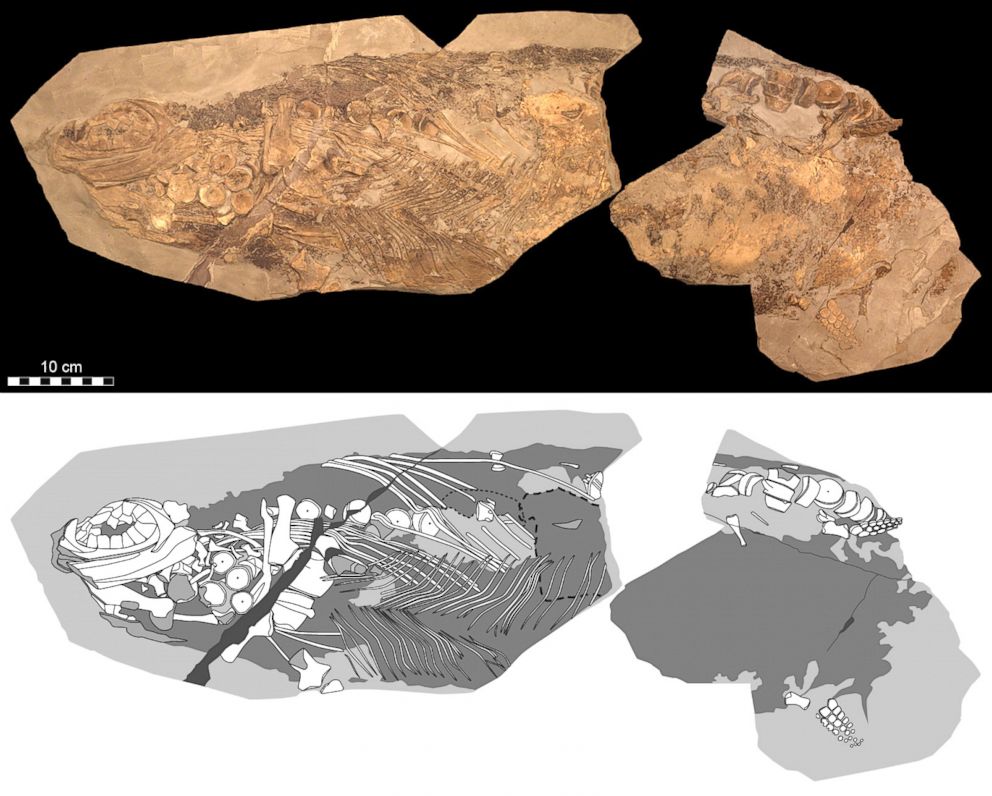

Scientists have identified an extraordinary specimen of fossilized blubber from a ‘fish-lizard’ that lived 180 million years ago, according to a new report in the journal Nature.

The blubber, a layer of fat beneath the skin of modern marine mammals that helps them preserve heat, indicates that the ancient 'sea monster' was warm-blooded, an unusual quality in a reptile, according to the report's authors.

The Jurassic-era sea creature, called an ichthyosaur, appears to have shared qualities of both a mammal and a reptile, according to Johan Lindgren, a senior lecturer at Lund University in Sweden.

"They looked kind of similar to dolphins, but the tail fin, it was vertical rather than horizontal,” Lindgren told ABC News. “They were reptiles," he said, while "dolphins, they are mammals like you and me. But ichthyosaurs, they were reptiles.”

Ichthyosaurs didn't just look like dolphins, Lindgren explained.

"In most aspects, I would say that they were living like dolphins," he said. "They were really dark ... almost blackish."

“I would imagine kind of dorsal skin, and some forms were deep divers that could venture down to perhaps several hundred meters and then go up again.” Several hundred meters is more than 1000 feet.

We cannot possibly predict the future of our planet without understanding the past. That is where all the data lie. Understanding how animals functioned in their past environments sheds light on how they might adapt to our own changing planet.

Lindgren said that to date, researchers have not be able to identified its exact age or gender.

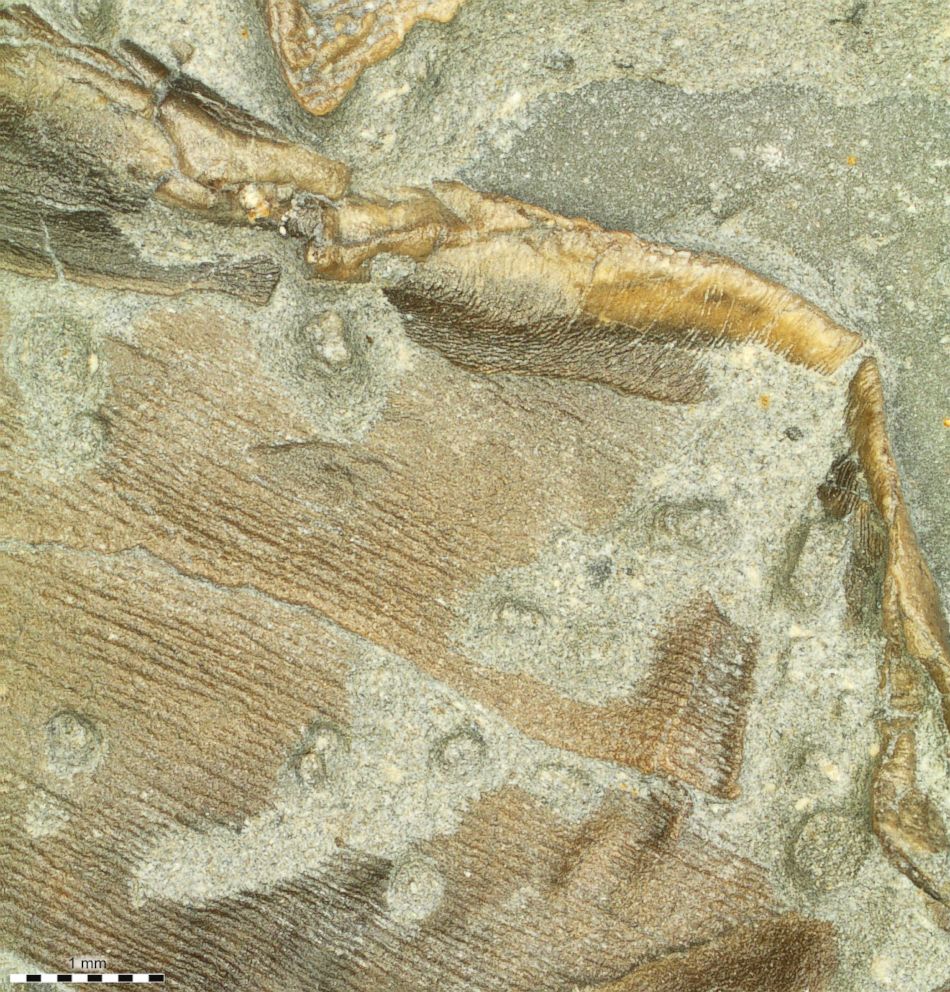

Lindgren said researchers found pigment cells concentrated on the dorsal side of the creature's body.

“So this animal was originally countershaded, meaning that it had a dark upper surface and the light belly."

Such natural 'camouflage' is common to modern animal groups, both terrestrial and marine life.

In most aspects, I would say that they were living like dolphins.

“It's a form of camouflage that you use when you need to hide in plain sight,” Lindgren said.

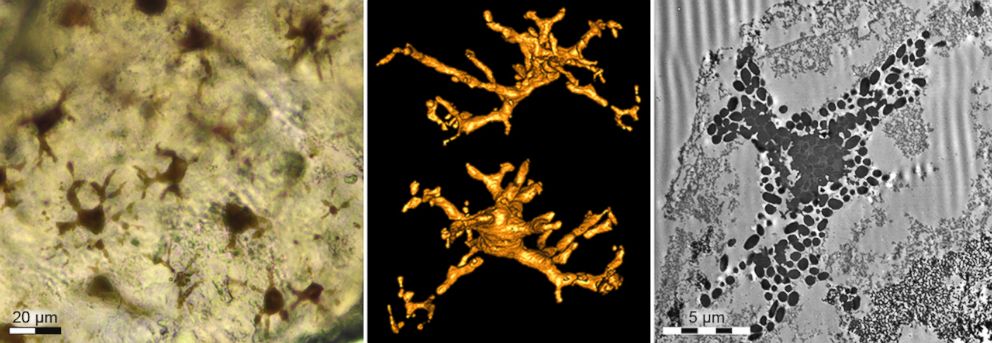

Sea minerals appear to have helped preserve and fossilize the creature's blubber.

“If you remove the minerals the original soft tissues are still there,” Lindgren said. “They were exceedingly rapidly-entombed in the minerals, so that must've happened, you know, during the decay of the animal. They were entombed in calcium phosphate and that entombment apparently preserved the tissues.”

The fossil dates back to the Jurassic era, said another co-author Mary Schweitzer, professor of biological sciences at North Carolina State University.

Schweitzer said studying this fossil could help explain ‘biological diversity’ and ‘what makes animal thrive.’

“We cannot possibly predict the future of our planet without understanding the past,” Schweitzer said. "That is where all the data lie."

“Understanding how animals functioned in their past environments sheds light on how they might adapt to our own changing planet.”