2nd parchment manuscript copy of the Declaration of Independence found in small British town

The manuscript was discovered by two researchers in Sussex, England.

— -- Last summer, Harvard researcher Emily Sneff and professor Danielle Allen were in a records office in a small town near England’s southern shore, perched over a tiny folder.

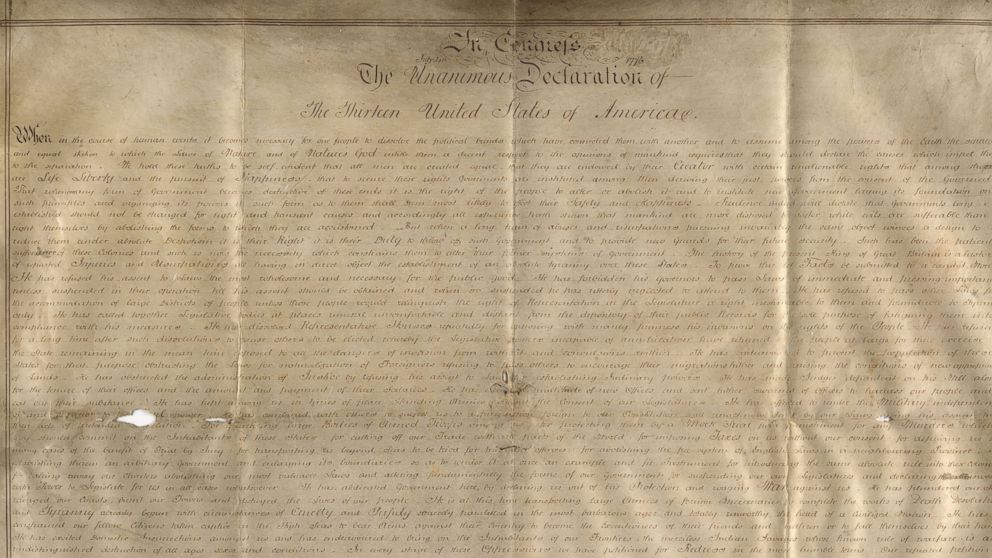

Pulling out a neatly-folded piece of parchment nearly three feet long, they suddenly found themselves holding an important piece of history: the only parchment manuscript copy of the Declaration of Independence besides the version sitting in the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

Sneff and Allen work at the Declaration Resources Project, which is working to develop a database of every known edition of the Declaration of Independence produced from 1776 through the 1820's. The document, ferreted away in a provincial town across the pond, has taken on the moniker “the Sussex Declaration.”

The Sussex Declaration is an American-made copy believed to have been created in the mid-1780's for James Wilson, a delegate to the Constitutional Convention who the researchers believe may have been trying to use the document to influence debate around the convention on behalf of the federal Constitution.

Sneff, the Research Manager for the project, discovered the document nearly two years ago in an online archive catalog and reached out to the office holding it. After seeing an image of the document and having a conversation with the conservator, she told ABC “we knew it was unlike any copy we’d seen before.”

The Sussex Declaration is similar to the Declaration in Washington, though because it is less worn, you can read every single word compared to the faded version sitting in the Archives. There’s one really significant difference between the two copies: The signed names at the bottom of the Sussex are scrambled so that they are not listed by state.

“The list of names was intentionally scrambled, we believe, to drive home the point that the signers of the Declaration of Independence signed as individuals, as a community,” rather than as a grouping of states, Sneff said.

At the time this document was likely created, American leaders were in a heated debate about what the new U.S. government would look like. Proponents of a constitution that would create a strong national, federal government began to grow in strength.

The research team believes the Sussex copy may have supported Wilson’s argument “that the authority of the Declaration rested on a unitary national people, and not on a federation of states,” according to a Harvard statement about the project.

When Sneff came across the document, she sent an email to Allen. Her response?

“Holy history, Batman.”

“We realized it was really a mystery and a mystery worth pursuing,” Sneff said. Now, nearly two years later, Sneff said “we’re getting very close to solving it.” The researchers presented their findings today a conference at Yale University, but Sneff said, “there’s a lot more work to be done.”

While they have determined the age and material of the Sussex Declaration, they’ve got two more steps to complete: determining conclusively who commissioned it and why, and finally how and why it got to England.

Their current hypothesis for its migration to England has something to do with the Third Duke of Richmond, Charles Lennox. Lennox became known as “the Radical Duke” after he emphatically supported the American Revolution in the House of Lords during the Revolutionary era. The document was one of several donated to the West Sussex Records Office, where it was found, that were probably owned by the Dukes of Richmond family.