Dying for salvation: A detained migrant's desperate plea for medical attention

Critics say the immigration detention healthcare system has failed detainees.

When Gerardo Cruz set out on his final journey across the U.S.-Mexico border, he felt he had no other choice.

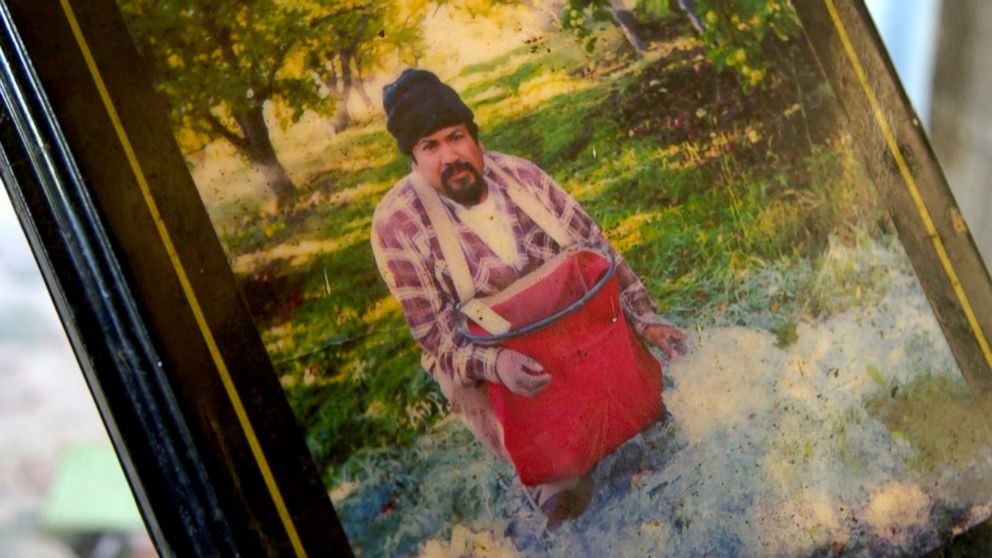

The 52-year-old father of six had been scraping out a living for himself and his family growing corn in a tiny village in a remote corner of Michoacán, one of Mexico’s poorest states, but an unexpectedly dry season had ruined his harvest and left him in debt, barely able to feed himself and his family.

There were few jobs to be had in this part of Mexico. He knew that he could find work, perhaps picking strawberries, in Fresno, California, more than 2,000 miles away. He had made the journey several times before, but he was younger then. He was still “very strong,” at least according to his wife, Paula. Still, she was scared.

“I told him not to go,” Paula said. “I said to him, ‘Don’t go. Why are you leaving?’ … But he said he could not support his family here and that’s why he was leaving. … He said it was so we could give the kids a better life.”

As he left, she comforted herself with the knowledge that no matter how many years they spent apart, he always returned home.

This time, however, would be different.

On Feb. 4, 2016, Cruz was discovered by U.S. Border Patrol agents between Tijuana and San Diego in a group led by a coyote – a cartel member who runs undocumented immigrants across the border. He was taken to the nearby Otay Mesa Detention Center, a sprawling facility owned and operated by the Nashville-based CoreCivic, Inc., one of a number of companies contracted by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to run detention centers across the United States.

He appeared to be healthy upon his arrival, as noted in his intake medical screening, but he would fall seriously ill in the following days, which would force him into the immigration detention center healthcare system.

In audio recordings obtained by ABC News and nonprofit criminal justice watchdog The Marshall Project, which were broadcast for the first time Wednesday on Nightline, Cruz’s cellmate can be heard in phone calls describing an increasingly desperate situation as he sought a significant medical intervention on his behalf. But as Cruz’s cellmate would later say in a sworn deposition, Cruz allegedly did not receive appropriate care, even as his condition visibly worsened, until he was near death.

Cruz’s family has since filed a lawsuit against both CoreCivic and the U.S. government, which provides all medical care and staff at the detention centers through ICE Health Services. Both declined ABC News’ requests for an interview.

In a statement, CoreCivic stressed that ICE is “solely responsible” for medical services in detention centers, but said the company “cares deeply about every person entrusted to our care….Our immigration facilities are monitored closely by our government partners, and every one of them are required to undergo regular review and audit processes that include ensuring an appropriate standard of living for all detainees.”

ICE, however, declined to answer specific questions about the Cruz case, citing pending litigation, but issued a statement saying “ICE takes very seriously the health, safety and welfare of those in our care.”

Under President Donald Trump, the immigration detention system has undergone a rapid expansion, and CoreCivic has reaped some of the benefits. A quarter of CoreCivic’s revenue now comes from contracts with ICE, a figure more than double that of five years ago.

“Those who choose to break our laws and enter illegally will no longer be able to use meritless claims to gain automatic admission into our country,” Trump said in November 2018 speech at the White House. “We will hold them for a long time if necessary.”

But in interviews with ABC News, critics of the immigration detention system described an overstressed healthcare capacity that has failed to the meet the needs of a particularly vulnerable population.

“I have visited these facilities,” Sen. Richard Blumenthal, a Democrat from Connecticut, told ABC News. “I have seen how threadbare the medical care is and how dehumanizing the conditions are. This kind of report is a call to action and, even more, an alarm for the American people that our current policies are failing. They're failing the standards of basic humanity and decency.”

Alejandro Chavez hadn’t known Gerardo Cruz for long, but he would still try to save his life.

They were arrested together and held in the same cell block, and perhaps because they were both from Michoacán, they became friendly. Chavez remembers Cruz eating, playing dominoes and walking in the yard, passing the time until their release.

But a few days after his arrival, according to court records, Cruz visited the center’s health clinic and was examined by a nurse. He complained of flu-like symptoms – a cough, sore throat, headache. Two days later, Cruz returned, reporting that he was in excruciating pain, a 9 out of 10 on the pain scale.

The next day, with Cruz confined to the bed next to him, Chavez called the Mexican consulate to request help from outside the walls of the detention center.

“He’s very sick, but he hasn’t been getting good medical care,” Chavez told the consular official in a recording obtained by ABC News. “He hasn’t eaten for several days, and anything he eats, he throws up, but they won’t take him to the hospital.”

Chavez claimed he told a guard – one he later said he sought out specifically because he spoke Spanish – that Cruz needed medical attention but was met with indifference.

“He says that they take them to the hospital only when they’re dying,” Chavez said in the recording. “I’m just hoping they’re not gonna wait [until] he dies.”

Anyone detained by the U.S. government – even undocumented immigrants – becomes the responsibility of the U.S. government. That includes providing detainees with appropriate medical care.

According to Dr. Marc F. Stern, who served as a healthcare consultant for the Department of Homeland Security from 2009 to 2014, that responsibility is both a legal and an ethical obligation.

“Somebody who is on their own has potentially the ability of going to a hospital, going to a doctor, taking responsibility for their own care,” Stern told ABC News. “When you put them in detention, they lose that ability.”

In his role at DHS, Stern was once tasked with investigating any allegations of inadequate healthcare within the detention system – which required him to visit detention centers, review medical records and conduct interviews – but he is unable to discuss that experience publicly without risk of running afoul a non-disclosure agreement he says he was required to sign as a condition of his employment.

“I can discuss what my activities were generally,” Stern said. “But I cannot discuss anything that I discovered, any conclusion that I arrived at during the time that I worked with the Department of Homeland Security.”

Stern has since begun reviewing the medical records of those who have died in immigration detention for Human Rights Watch, the prominent international research and advocacy group, and he says those documents detail a “broken system” that has allowed detainees to continue “dying needlessly.”

Human Rights Watch reviewed the 52 publicly available death reports of the 81 detainees who have died in detention since 2010 and determined that almost half of those deaths were linked to substandard care.

The specific issues vary, Stern said, but boil down to two main problems – a lack of spending and a lack of oversight.

“You get what you pay for,” Stern said. “You get what you design.”

Chavez said he could do little more than watch as Cruz suffered.

With Cruz unable to leave his bed, Chavez began bringing food to Cruz, but in a Feb. 20 call to his wife, Maribel, Chavez reported that Cruz had lost his appetite.

“Gerardo hasn’t eaten for a week, you know,” Chavez said in the recording. “He doesn’t wanna eat. He can’t get up at all. … They are giving him some meds. He has pills and all that but I need to figure out how he can see the doctors so he gets fluids and all that. Like stronger medication. He can barely speak by now.”

Nurses who examined Cruz, ICE medical records show, had given him over-the-counter cold medications and pain relievers, but Cruz’s condition continued to deteriorate.

According to Chavez, he approached that same guard again to ask for help.

"And why do you want to help him out?” Chavez later said in a deposition the guard told him in reply. “Is he your wife or your girlfriend?”

A former CoreCivic training manager, who was promoted through various positions in 11 years within the company and was working at Otay Mesa until taking medical leave shortly before Cruz arrived, told ABC News – as he also said in a deposition – that he had become increasingly troubled by the pressure the company was putting on its employees at the facility.

At their old facility, he said, officers had previously supervised about 64 detainees at a time, but after Otay Mesa opened in 2015, officers began supervising about 120 detainees at one time.

The former manager said morale plummeted and turnover soared, which created a hazardous situation for the detainees.

“I believe they overworked the staff,” said the former manager, who is now a key witness in the Cruz family’s lawsuit but asked not ABC News not to publish his name. “Put them into position to where [it was] very difficult to almost near impossible to stay fully coherent based on hours.”

He tried to report his concerns to management, he said, but to no avail.

“When I spoke up for the staff, when I spoke up for what was right – spoke up for the facility, the detainees, the inmates,” he said, “I became Public Enemy No. 1.”

In a statement to ABC News, CoreCivic disputed criticism of staffing levels at Otay Mesa, saying “the staffing pattern at the facility was appropriate and within the standard of care for a detention facility.” The company also denied the allegations from their former manager.

“Every complaint brought by [the former manager] was carefully investigated, including his claims of retaliation, which are taken extremely seriously,” the company said. “After a comprehensive review, none of his claims of retaliation were found to be substantiated.”

But the former manager believed the situation made a “major incident” inevitable.

“One-hundred percent I knew bad things were gonna happen,” the former manager told ABC News. “There was no other way around it based on the situation it was.”

In a call to his wife on Feb. 26, Chavez painted a desperate picture.

He said he returned from lunch that day to find Cruz lying in blood-soaked sheets. He and another detainee pulled Cruz out of the bed, he said, and helped him sit at a nearby table.

Cruz was pale, he said. His body was swollen. And he began to cough up blood. But when the guard arrived, Chavez later said in a deposition, he yelled at Cruz for making a mess.

“He yelled at him in a really bad way,” Chavez said, “because he said, ‘That’s the table where you eat, and you’re getting it all full of blood.’”

But later that afternoon, according to his family’s lawsuit, Cruz’s condition would spur action. Cruz was taken to the medical clinic, where a doctor would summon paramedics to bring him to Scripps Mercy Hospital in Chula Vista.

Chavez sounded shaken by the incident. The previous day, he told his wife, he had urged Cruz to get better so they could drive back to Michoacán together after their release, but now he worried that Cruz might not make it. His wife tried to comfort him.

“Hey, he made it this far,” she told him in the recorded call. “If he didn’t die here, he’s not gonna die.”

She was wrong. The San Diego Medical Examiner’s investigative report notes that Cruz was intubated by paramedics, placed on mechanical ventilation in the emergency room and then admitted into intensive care.

Tests revealed a litany of serious conditions, including pneumonia, diabetes and hypokalemia, and he remained on a ventilator while he underwent dialysis. But three days later, he went into cardiac arrest, and efforts to revive him failed. Cruz was pronounced dead, 25 days after being detained, 18 days after arriving at Otay Mesa Detention Center, and 17 days after first seeking medical attention.

CoreCivic claims Cruz was seen by medical staff six times. But according to court documents, he was only seen by a doctor once. And according to his family, it was already too late.

Critics say Cruz’s death and the deaths of some other immigrants who have fallen ill in detention were preventable.

Both Dr. Stern and Clara Long, a senior researcher at Human Rights Watch who focuses on immigration and border policy, pointed to a host of potentially deadly problems within the immigration detention system - ranging from guards allegedly impeding detainees’ access to healthcare to medical professionals making questionable decisions in emergency situations – that the U.S. government needs to address.

“The federal government has promised an adequate standard of care,” Long told ABC News. “But it is not delivering on that promise.”

She called ICE’s oversight of the system “a sham,” in which inspections of facilities and investigations of suspicious deaths of detainees rarely, if ever, lead to improvements.

And those problems, she said, are only getting worse, as more and more people are placed into the system.

“The Trump administration wants to dramatically expand immigration detention … but without asking for resources to improve their oversight and monitoring systems,” Long said. “Which means more people exposed to dangerous conditions that we’re finding are linked to death again and again.”

CoreCivic, however, appears to see an opportunity in President Trump’s hardline policy on the detention of undocumented immigrants.

The company donated $250,000 through its subsidiaries to Trump’s inaugural fund, and when asked about the company’s prospects under Trump, CoreCivic President and CEO Damon Hininger signaled that he expected the new administration to be “friendlier” to private sector involvement in immigrant detention.

“I think there are several things that we can look forward to, as a company, in the next year. First of which is immigration,” Hininger told CNBC in December 2016. “If there is a need for more detention capacity on the border, we can provide that solution.”

Several weeks after Cruz’s widow Paula received a phone call from a U.S. immigration official notifying her of Cruz’s death, Paula said she heard there was a man looking for her in a nearby village.

It was Cruz’s cellmate Chavez. She met him there, she said, and heard his account of how her husband had suffered.

“Señora, this is what happened,” she said he hold her. “Your husband was sick … and they ignored him.”

This time, she comforted herself with the memory of their final words to each other, in which they reconciled nearly four decades of marriage with the fights they would sometimes have.

“He asked me to forgive him,” Paula said. “And we forgave each other.”

For Paula, his death was nothing short of a crime. And she wants someone to be held responsible.

“What else can you call that, other than they killed him?” Paula said. “They refused to help him. It they had helped him maybe he would still be alive. But they didn’t.”

In 2017, Paula filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the U.S. government, CoreCivic and the guard, alleging Cruz “would be alive today if the authorities had honored their legal and moral duty to care” for him.

The guard, who now works directly for ICE, declined to comment to ABC News, but in a deposition, the guard denied having any memory of Cruz or any memory of interactions with Chavez.

“In the eleven years that I've done corrections, military, and now that I'm with DHS, I've never shown that kind of character,” he said. “That’s not who I am.”

In a statement, the company said “there is nothing to suggest” the guard “impeded [Cruz’s] access to care or failed to summon medical care” for Cruz and denied that the guard made those callous statements, saying the “alleged conversation” with Chavez “could not have taken place” because the guard was not stationed in the same area at the time.

But in testimony obtained by ABC News, one of CoreCivic’s employees acknowledged that Otay Mesa is an “unrestricted, ‘open-movement’ facility” in which detainees can freely move from one area to another.

In the last few weeks, calls for greater oversight of the system have emerged from some of the country’s most powerful people.

On Nov. 15, nearly a dozen Democratic senators sent a letter to CoreCivic President and CEO Hininger expressing concern about the treatment of detainees in CoreCivic facilities and requesting information about the company’s operations.

One of the letter’s signees, Sen. Blumenthal, told ABC News that he plans to push for a review of the government’s policies early next year.

“Shining a light on these kinds of failings [of medical care in detention facilities], and they are failings of morality as well as law, ought to be one of our mandates in the earliest days of the next Congress,” Blumenthal said. “We need hearings, oversight, investigation, fact finding, evidence, because this administration must be held accountable.”

Angela Kim Zugman, the San Diego-based attorney representing Paula in the lawsuit, hopes that Cruz’s case could spark a change in the system, one that could improve the lives the of the thousands of immigrants who pass through it every year.

“Justice, for me, is to educate the American public … as to what’s actually happen in these facilities,” Zugman said. “How are these detainees actually bveing treated? And what can we do to change the system that they’re stuck in?”

But Paula fears those efforts might prove to be too late for her, too.

“If he had not gone, he would not have died. And he would be here to support me, to provide for me, to keep me company,” Paula said. “I am very sick. Who is going to feed me? Who is going to help me? Nobody.”

John Carlos Frey is a five-time Emmy Award-winning journalist who specializes in coverage of the U.S.-Mexico border for The Marshall Project.

ABC News’ Dylan Goetz, Jinsol Jung, Halley Freger and Emily Ruchalski contributed to this report.

This report was featured in the Thursday, Dec. 13, 2018, episode of ABC News' daily news podcast, "Start Here."

"Start Here" is the flagship daily news podcast from ABC News -- a straightforward look at the day's top stories in 20 minutes. Listen for free every weekday on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, iHeartRadio, Spotify, Stitcher, TuneIn, or the ABC News app. On Amazon Echo, ask Alexa to "Play 'Start Here'" or add the "Start Here" skill to your Flash Briefing. Follow @StartHereABC on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram for exclusive content, show updates and more.