2020 Democrats jockey for the progressive mantle in the era of Trump

What does it mean to be a progressive in today’s Democratic Party?

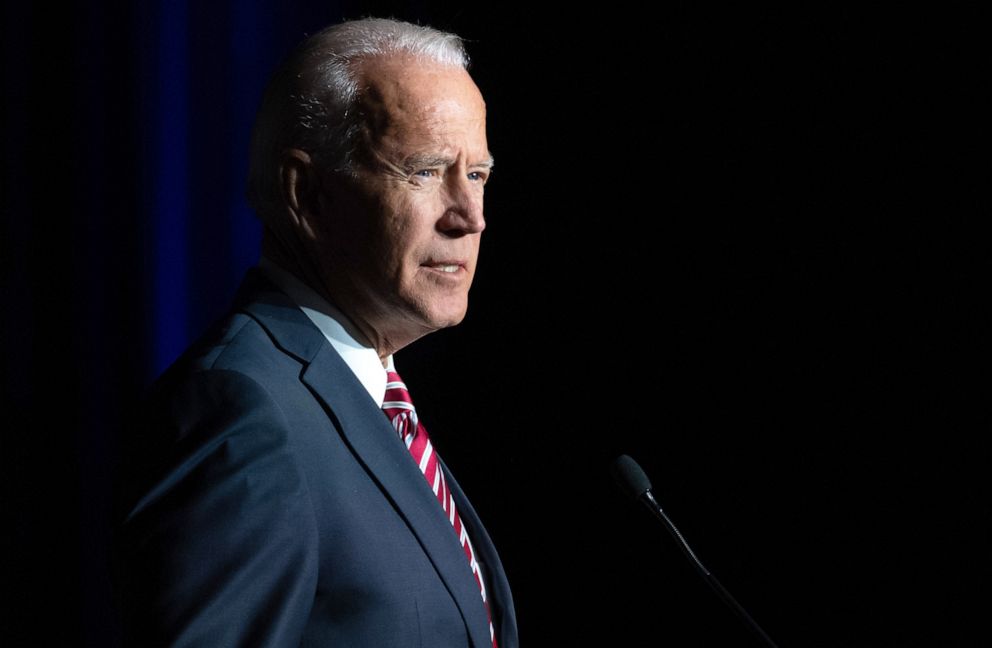

At the end of what appeared to be an introspective survey of the progressive and moderate divide splintering the Democratic Party, former Vice President Joe Biden declared before a crowd of reporters swarming him on a Washington city block, "I'm an Obama-Biden Democrat, and I am proud of it."

"The definition of progressive now seems to be changing," Biden said Friday when pressed by a reporter in the impromptu gaggle about a previous comment he made on having the most progressive record among the field of 2020 presidential candidates. "It's, are you a socialist? That's a real progressive ... I'll stack my position against anybody who has ever run or is running now or who will run."

As he sized up the current state of Democratic politics and gave a nod to the pre-Trump era, Biden also attempted to define the Democratic Party as the party tries to define itself amid a teeming presidential primary.

Even as Biden struggles to respond to a flurry of accusations of inappropriate touching from multiple women before officially announcing his widely expected campaign, he speaks to a debate brewing within Democratic circles for decades: what defines a "progressive."

This unfolding central theme this cycle was given new life during Sen. Bernie Sanders' unexpectedly competitive challenge to Hillary Clinton in the 2016 primary.

President Donald Trump's polarizing positions on immigration, climate, health care and the economy often enrage the progressive base on a daily basis. As such as universally effective primary foil, some Democrats seeking to claim the "progressive" mantle do not have to shy away from the label in the same way that candidates like Clinton and others have in the past.

"[Sanders] actually helped move the party and the party has changed since then, and the context of Trump gives Democrats a little more freedom to go into new places," Julian Zelizer, a professor of history and public affairs at Princeton University, told ABC News.

While the former Delaware senator holds onto his moderate label, saying Friday the vast majority of the party is "still basically liberal to moderate Democrats in the traditional sense," progressive groups reject Biden's thinking in favor of candidates who embrace this newfound freedom to pitch policy ideas once rejected by a wide swath of the party.

"Joe Biden doesn't want to acknowledge that the winds have shifted in the Democratic Party away from compromising with Republicans and corporate donors and toward the grassroots progressive movement," said Waleed Shahid, communications director for Justice Democrats, the progressive group that backed Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ayanna Pressley in their bids to unseat longstanding Democratic incumbents. "It's because so-called centrists like him are the last to shift with the winds of change."

"The center of the party and the center of the general American electorate has moved massively in an economic populist direction, where big ideas that were never even contemplated by the Obama-Biden administration are now squarely in the mainstream of public debate and supported by most voters," said Adam Green, the co-founder of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, who is backing Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., in the 2020 primary. "The center of gravity has shifted."

Bernie tries to set the early tone

For his part, Sanders' 2020 policy platform is nearly identical to his 2016 agenda, emphasizing universal healthcare and tuition-free public universities as the cornerstones of his campaign.

But new this cycle is the idea of using the campaign itself as a way to distinguish yourself from the field.

Earlier this month, Sanders' campaign became the first in history to unionize and has recently committed to offset the greenhouse gas emissions generated by his cross-country travel by supporting renewable-energy and carbon-reduction projects.

In the early stages of the primary, the Democratic candidates have yet to face each other on a debate stage, but already the tone, tenor and substance around how tightly the party should embrace the term progressive is shifting, thanks in at least some part to Trump.

"In some ways the unconventional, unpredictable and -- some would say -- radical aspects of the Trump presidency, have made some Democrats more willing to say why do we have to play it safe all the time? Why not be bold?" Zelizer said.

The 2020 definition of progressive

The 2020 contest has already ushered in an unprecedented number of Democratic candidates: 17 and counting. In one of the most diverse fields competing for the nomination, and the chance to unseat Trump, standing out on mainstream issues, such as, taxes, the economy or health care is shaping up to be an arduous task.

Although the Democratic hopefuls represent a breadth of ideologies and range on the political spectrum from socialist to moderate, many of the candidates are casting themselves as progressive or threading progressive themes into their platforms.

"I'm in the getting-things-done wing," Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., told NBC News. "And I am a progressive."

"I cannot only inspire the base on progressive issues that I'm running on like actually passing a 'Green New Deal,' 'Medicare for all' -- health care is a right, not a privilege -- but also being able to reach out to those red and purple voters to be heard and to have them come to the table and be represented," Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, D-N.Y., said in an interview with CBS News.

"I view myself as a progressive, but these labels are becoming less and less useful," said South Bend, Indiana Mayor Pete Buttigieg, a more moderate voice in the field, on Fox News Sunday.

At campaign stops, town halls and interviews, the candidates have been questioned early about their claims to progressivism, and some are responding by turning to more audacious policy proposals to set their agendas apart from the pack.

Over three months into the election season, the conversation about what being a "progressive” means is shifting away from the traditional set of policy prescriptions and towards a debate over a series of structural reforms that once occupied the periphery and challenge Constitutional norms. Seeking to find a broad and appealing message to court voters, the party is debating, and some are even embracing, a slate of issues like changing campaign finance rules, reforming the Senate filibuster, eliminating the Electoral College, expanding the Supreme Court bench, and paying reparations for African Americans.

At the recent "We the People" summit, top Democratic presidential candidates made their pitches for bold, structural change to an eager audience of progressive activists gathered in Washington.

"Let's abolish the Electoral College," former Texas Rep. Beto O'Rourke said. "If we got rid of the electoral college, we'd get a little bit closer to one person, one vote in the United States of America."

"Everything starts with big, systemic change. How do we reduce the influence of money and power in Washington? We start with an anti-corruption bill, there's part one," Warren, one of the most ardent progressive allies, told the audience.

"Some people say, 'Let's get rid of the filibuster,' and I feel that sense of urgency," New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker said. "But let me tell you what I worry about. In my community, if Mitch McConnell, Paul Ryan and Donald Trump had two years like they just had without me in the Senate and other noble progressives who fought them with you to prevent the taking away of health care, we would have lost that battle -- Obamacare would have been gone.”

While several of the 2020 hopefuls, including Gillibrand, Warren, Buttigieg, California Sen. Kamala Harris and former Texas Rep. Beto O'Rourke, have signaled a willingness to consider packing the court with more justices, on reparations, a far more nuanced debate around how to right the wrongs of hundreds of years of slavery -- appears to be splitting the party, which will, in part, rely on a coalition of African American voters to win back the White House.

"I think a lot of Democrats understand that they can't simply push aside some of the issues that have been raised and I think some of them are genuinely open to listening and being responsive and say maybe these are the ideas we need to be fighting for," Zelizer said. "I think that progressive and the Democrats are sympathetic to these ideas ... they're open to now thinking out of the box, politically, and I think that's why some of the issues are emerging as well."

These issues that have recently entered the mainstream fold, for progressive groups, reinforce the notion that the party as a whole is moving in a leftward direction.

"The debate in the Democratic primary will not be conservative democrats versus progressive democrats. It will be fine status-quo democrats versus bold transformational potential presidents," Green said.

"What voters are hungry for now as they were in 2016 is someone who will shake up the current political and economic system," he added. "They want big structural change...times are changing, and people are more willing to challenge corporate power and challenge systemic racism and just fundamentally talk about shaking up the current system, not just small-bore tweaks within the current system."

But as questions arise about if the party is moving too far to the left for the eventual general election against Trump, Biden, who is the polling front-runner despite not yet entering the race, welcomes that debate.

"The progressive left, it should be welcome," he said Friday. "We should have a debate about these things. That's not a bad thing."