My ancestors were owned by Georgetown University, I soon graduate from there: COLUMN

"I’m still processing exactly what that means."

I always thought my family was from Louisiana.

I never had any reason to believe otherwise, as our roots in the state-run so deep.

From my paternal great-great-great grandfather T.B. Stamps who was an African American state senator in 1872, to my grandmother's gumbo that simply cannot be replicated, our connection to Louisiana has, and always will, be strong.

Growing up, my siblings and I were always told the stories of our ancestors in Maringouin, La. A small rural town in our state that, until recently, we never visited.

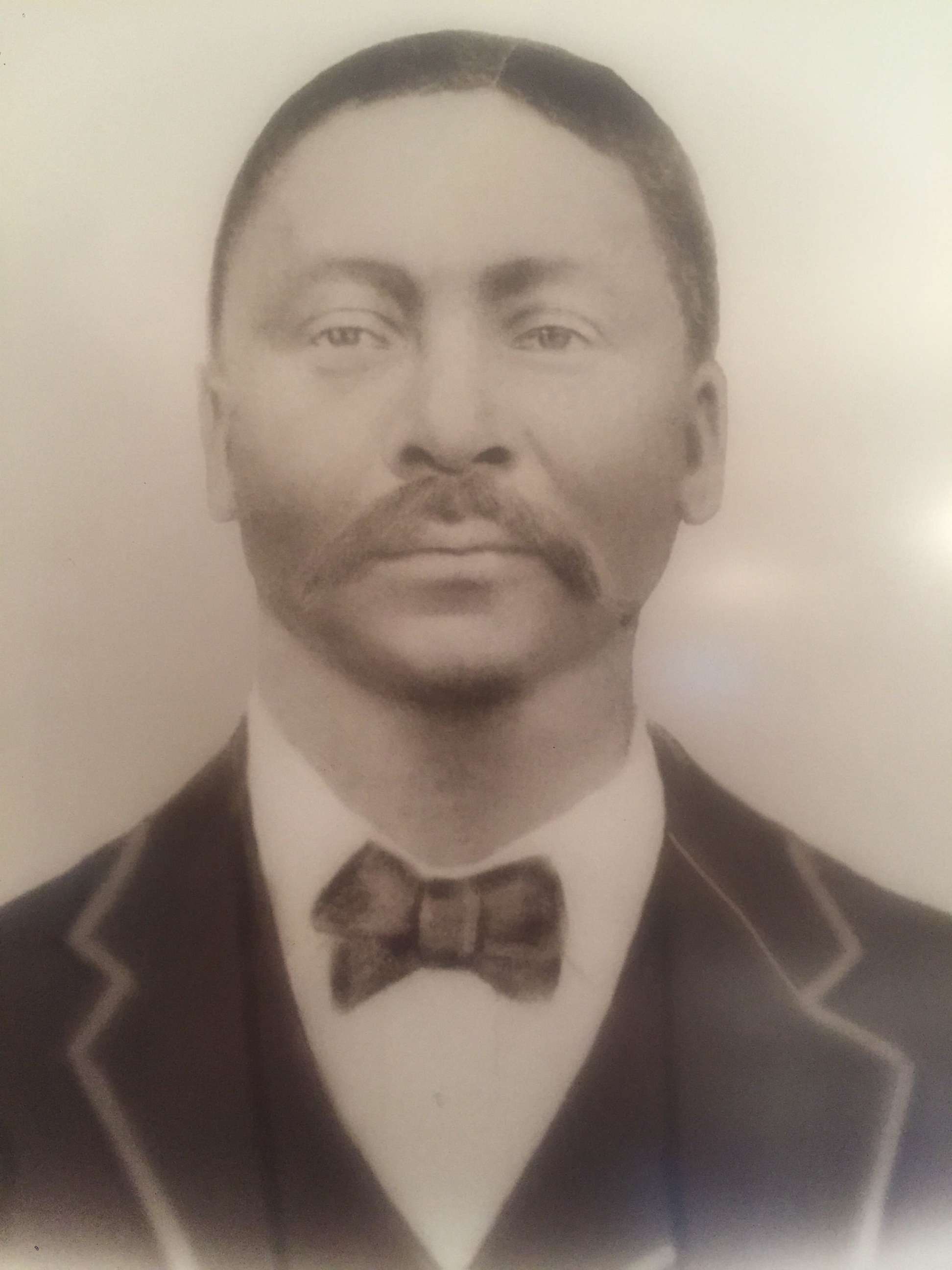

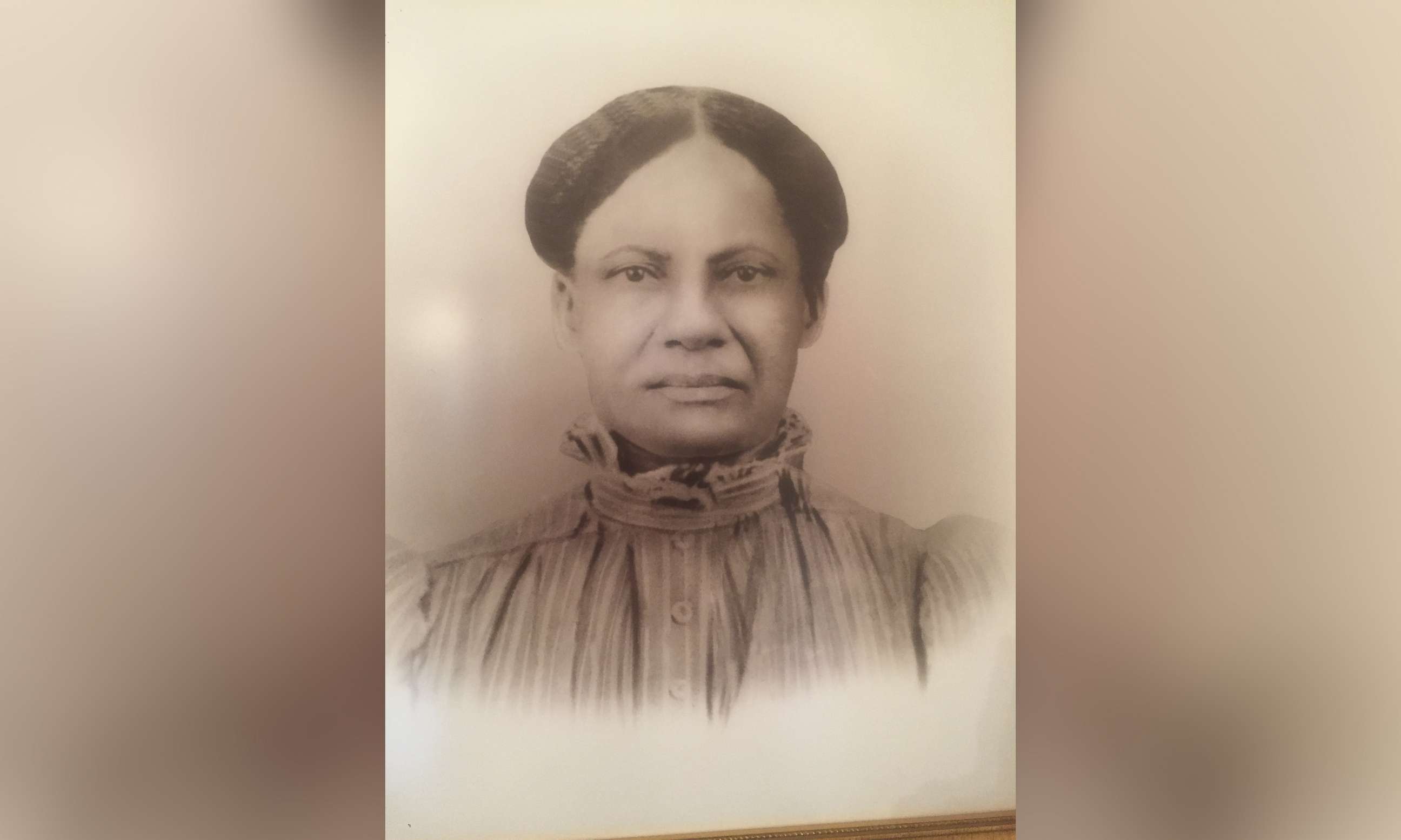

Our maternal grandfather, Shepard Green, grew up there and made sure to pass down our family history from generation to generation. I was told stories of William and Charity Harris, my great-great-grandparents, born into slavery on the West Oak plantation in Maringouin around the 1850s.

Shortly after the Civil War ended, William Harris worked for Emily Woolfolk, the owner of the West Oak plantation where he had been enslaved.

His family would pool their money and resources together and were able to purchase property. He also donated land that he acquired to the Catholic church to found St. Mary’s Chapel, and a school for "colored" children of the same name "for the purpose of assisting and advancing Christian education among the colored children," according to a manuscript maintained by the Iberville Parish Courthouse from 1897.

This is where I always thought my family’s history began in the United States, and I had great pride in this history. My paternal great-great-great grandfather Stamps was not only a state senator, but a civil rights activist who in 1875 ended Jim Crow seating in the historic St. Charles Theatre in New Orleans, La.

It wasn’t until April 16, 2016 that I began to learn the complex nature of my family history -- a truth that had been suppressed for years.

Almost three years to the day, I was home with my family as my mother, Sandra Thomas, was reading the New York Times and my siblings and I were in our rooms relaxing.

My mother saw on the cover of the New York Times a story with the headline, “272 Slaves Were Sold to Save Georgetown. What Does it Owe Their Descendants?” The story featured a photo of the Immaculate Heart of Mary cemetery where many of my ancestors have been laid to rest.

“I couldn’t imagine why it would be on the cover of the New York Times,” my mother would later tell me. “I thought, ‘What’s up with Maringouin?’”

From there, my mother read the story and decided to pull up the slave manifest published online by Georgetown University.

On that slave manifest she was shocked to find the names of my maternal great-great-great grandparents Sam and Betsy Harris, owned and sold in 1838 by Georgetown University and the Society of Jesus to prevent the school from bankruptcy. The survival of Georgetown University was, in part, a direct result of this sale of 272 human beings.

We knew of Sam and Betsy, as they were the parents of my great-great-grandfather who started the first school for African American students in Maringouin, William Harris. The family always believed though that our history began in Maringouin. We had no idea of any history outside of Louisiana, and definitely never considered a connection to such a world-renowned school such as Georgetown University.

When my mother shared this news with us via text message I went through a series of emotions.

The first to surface was pain.

As an African American, I always knew that I descended from enslaved people. But I began to imagine the horrific lives they must have been forced to live and the impact their enslavement had on their descendants for generations to come.

The pain they endured during enslavement is seared into my soul and the souls of all descendants of enslaved people in this country.

To know that my ancestors were enslaved by Catholic religious leaders, people who came to the United States to spread the word of Jesus, was especially hurtful.

I also felt a sense of understanding about certain aspects of my life and family.

This discovery that my ancestors were enslaved by the Society of Jesus and Georgetown University provided a much darker realization as to where my family’s connection to the Catholicism may have begun.

On my mother’s side of the family we were raised devout Catholic -- part of the reason we believed we were from Louisiana due to the century’s long history of black Catholics in the state.

I graduated high school from Ursuline Academy of New Orleans, both the oldest continuously-operating school for girls and the oldest Catholic school in the United States. For four years I studied the "history" of the Catholic church and knew about the role the Catholic church played in conquering the Americas and the treatment of indigenous people.

However, not once do I recall learning about the slave-owning connection to Georgetown University.

When I was a young child my father, Joseph Thomas, had a law practice in Washington, D.C. and we had a second family home in Georgetown. My mother used to push me and my brother in strollers around the Georgetown campus, completely unaware of our tie to the university.

“I always felt a deep connection to the area that I didn’t quite understand,” my mother said once we discovered our family's history with Georgetown.

I also felt a pervading sense of disappointment.

Unfortunately, my family's tie to the church is not uncommon.

Georgetown University and the Jesuits have, for decades, had the slave manifest in their archive --- the key to the history of thousands of descendants from this sale all across the world.

I often wonder if the story had never published if my family and others would ever know our true history in the United States.

Lastly, I felt extremely grateful.

Even though the way my family found out this history was not ideal, we are still extremely grateful to have the information. Many African American families in this country will never be able to trace their history back this far, thus never truly knowing where their story began in the country we call home.

One unexpected result of this discovery was that it ignited a passion for journalism and storytelling. This story, my story, sparked a new passion for journalism inside of me.

I wanted to tell stories that changed people’s lives -- stories that bring truths to the surface that have been purposely buried or silenced.

I received my undergraduate degree from Louisiana State University and had a great job in my home town of New Orleans, La. when this story broke.

And when Georgetown University announced that they would be offering preferential admittance status, otherwise known as “legacy status,” to the descendants of the 272 enslaved people they owned and sold, I wasn’t immediately sure what that would mean for me.

Essentially, preferential admittance status gives an application for admittance a boost when applying. This preferential admission status provides the same attention given to legacy applicants who are descendants of faculty, staff or alumn.

I never considered going back to school until this opportunity arose.

But, after much reflection, I decided to apply and was accepted into Georgetown University’s School of Continuing Studies to pursue a masters of professional studies in journalism.

When I enter through the big iron gates and see the undergraduate students laughing and relaxing under the cherry blossoms, the images are juxtaposed with thoughts of what the 272 enslaved people had to endure so students could enjoy that luxury.

It sometimes frustrates me.

Last July, I took a trip to the Georgetown University campus with Melisande Short-Colomb, one of the other descendants.

The two of us had just finished talking about what both of our experiences have been like since we decided to enroll as students at the university when a sudden light bulb went off in my head to go on a quick adventure to the Jesuit Community Cemetery to find a deceased priest.

One of the primary attractions on the school's campus is the Jesuit Community Cemetery, first established in 1808 as the final resting place for Jesuits affiliated with the university.

So we trekked in the blazing summer heat to the middle of campus to search the graveyard of over 300 priests.

We examined every tombstone, row after row, hoping to find one particular priest out of the bunch. After 10 minutes of searching and what felt like a dozen mosquito bites later, I was feeling hopeless.

But then I heard a scream from Short-Colomb, "Ah, I found him! There he is."

I ran over, and to my surprise, we did in fact find the priest we were looking for. The tombstone before us read Rev. Thomas F. Mulledy, the priest who helped orchestrate the sale of my ancestors and others to Maringouin.

We stood in silence for a few minutes, in awe that we were standing above the man who never envisioned, or probably wanted, us to be where we are today. A man of God, who deemed it necessary to enslave and sell one community so that another can benefit.

Surprisingly there were no tears shed there. In fact, after our silence we started laughing.

"Whelp Mulledy, look at us now," I said with almost uncontrollable laughter at this unbelievable circle of life moment.

"He's probably rolling in his grave right now," she said through her spurts of laughter.

Since 2016, Georgetown has taken some actions toward atonement.

First came the preferential status granted to descendants if they chose to apply to the university. Then there was a liturgy service with descendants, where members of the university and the Jesuits asked for forgiveness for their sins.

The university also renamed a building on campus, once named after a school president who oversaw the 1838 sale, to instead honor Isaac Hawkins, who was one of the 272 enslaved and whose name appeared at the head of the bill of sale.

Meanwhile, a group of students who call themselves "Students for GU272," drafted a referendum that which would increase tuition by $27.20 per semester to create a fund benefiting descendants of the 272 enslaved people.

By almost a 2-to-1 margin, students approved the measure, which still must be approved by the university to go into effect.

Todd Olson, vice president for student affairs at Georgetown University, in a statement issued after the vote, lauded the students' efforts saying " university values the engagement of our students and appreciates that 3,845 students made their voices heard in yesterday’s election. Our students are contributing to an important national conversation and we share their commitment to addressing Georgetown’s history with slavery."

The university has vowed to "carefully review the results of the referendum, and regardless of the outcome, will remain committed to engaging with students, Descendants, and the broader Georgetown community and addressing its historical relationship to slavery," Matt Hill, the university's media relations manager, told ABC News in a statement.

Today, I am currently one month away from graduating from the school that enslaved my ancestors.

I’m still processing exactly what that means.

My brother, Shepard Thomas, is currently a junior studying math and psychology at Georgetown.

I would definitely say that deciding the join the Hoya family as a student definitely was worthwhile.

I've had some amazing professors who have pushed my journalistic abilities and have motivated me to become a stronger story-teller. I've also made some fantastic friends from extremely diverse backgrounds that have helped provide me a more holistic view of the world that helps inform my writing.

I can say without a doubt that these experiences and opportunities have benefited me and are a direct result of my attendance at Georgetown.

The year and a half I spent at Georgetown University was a period of intense growth. It's wasn't easy to become part of a community that enslaved my ancestors, thus changing the complete trajectory of my family's history.

And I know for certain that Sam and Betsy Harris never imagined during their time of brutal enslavement in the 1800s that their descendants would receive degrees from the same institution that kept them in chains.

Editors Note: Elizabeth Thomas is a desk assistant in the Washington D.C. bureau of ABC News.