Budget reconciliation: How COVID relief could pass without GOP support

The obscure, but powerful, tool was last used by Republicans in 2017.

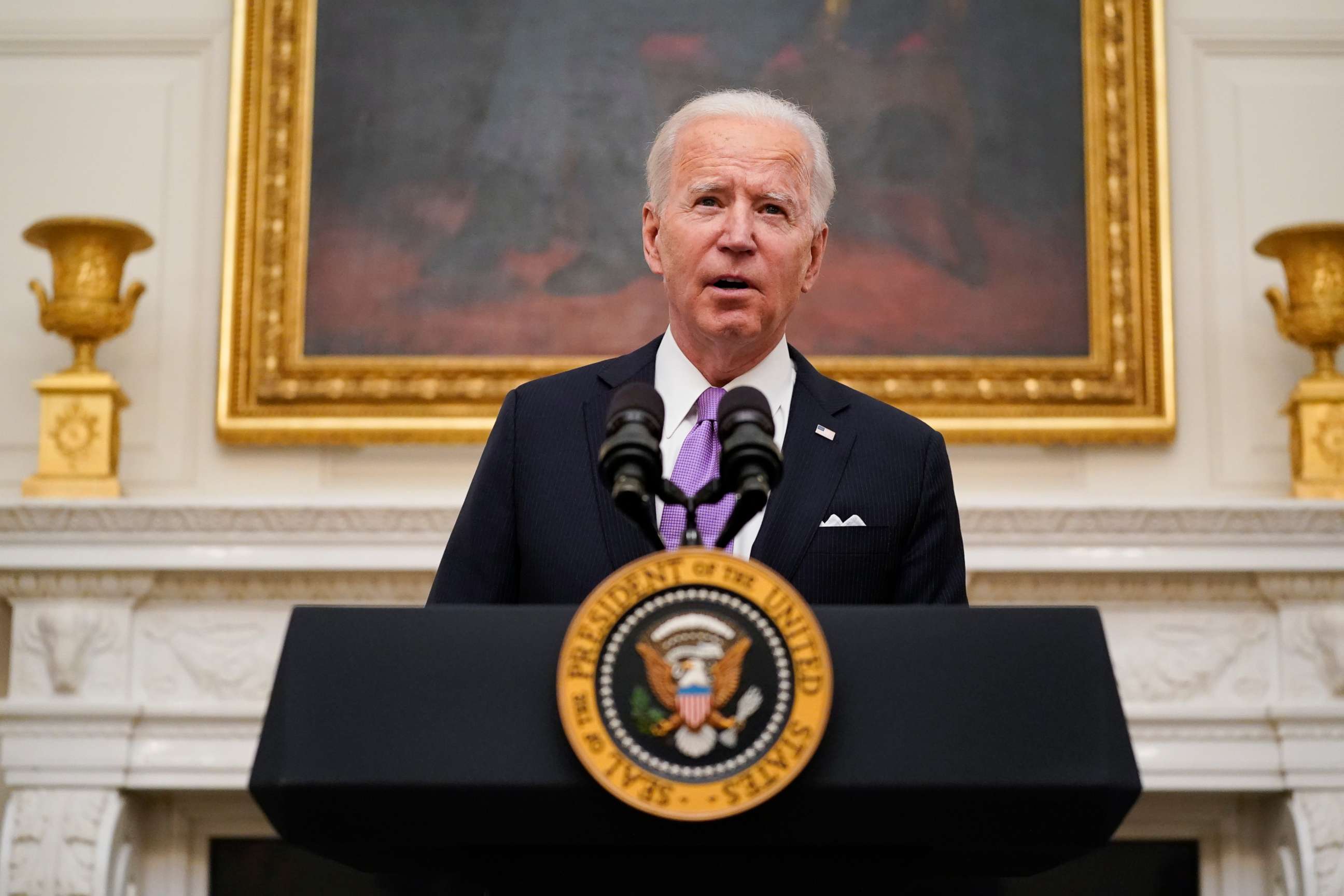

As President Joe Biden attempts to pass his $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief proposal with Republican support, Senate Democrats are working to move ahead without the GOP using an obscure, but powerful, procedural tool known as reconciliation.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi announced Monday that they have filed a joint budget resolution -- the first step to potentially enacting a budget reconciliation bill.

"It makes no sense to pinch pennies when so many Americans are suffering," Schumer said in floor remarks Monday. "The risk of doing too little is far greater than the risk of doing too much."

Reconciliation is notable because it allows any legislation crafted within its strict parameters to pass in the Senate with a simple majority of 51 votes, as opposed to 60, which is needed to overcome a filibuster. But it is a complicated process beholden to a strict set of rules.

Reconciliation was established by the Congressional Budget Act of 1974 to fast-track Congress' ability to change laws in three areas of the budget: revenue or taxes, direct spending -- such as Medicare and Medicaid -- and debt limits.

Since 1980, 21 budget reconciliation measures have been enacted into law, according to the Congressional Research Service. Most recently, it was used by Republicans in 2017 while passing the 2018 fiscal budget to overhaul the tax code -- including permanently repealing penalties associated with the Affordable Care Act's individual mandate -- and allow oil and gas drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. One of Biden's first actions as president was to place a temporary moratorium on that activity.

As the Biden administration works to move its COVID-19 rescue plan, Schumer appeared to lay out a timetable for Republicans to get on board before Democrats move ahead with reconciliation.

"We hope they join us this week. If they don't, we're moving forward on our own," Schumer said Saturday on MSNBC's "Politics Nation."

Schumer's remarks echo ones Biden made the day before. When asked by reporters as he left the White House Friday if he supported passing coronavirus relief through reconciliation, the president said, "I support passing COVID relief with support from Republicans if we can get it. But COVID relief has to pass. There's no ifs, ands or buts."

In a Senate now split 50-50, reconciliation could allow Democrats to pass legislation without a single Republican in favor, with Vice President Kamala Harris able to cast a tie-breaking vote. That presumes all 50 Democrats are on board this time, but Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., has expressed the importance of acting in a bipartisan way, so leadership is keeping an eye on him. The moderate Democrat was none too pleased when Harris recently traveled -- unannounced -- to his state to push the administration's sweeping pandemic relief measure.

"I saw (the interview). I couldn't believe it. No one called me. We're going to try to find a bipartisan pathway forward. I think we need to," Manchin told WSAZ.

Should Congressional Democrats invoke reconciliation, here's what the procedure would look like, from "vote-a-rama" to the "Byrd rule."

Step 1: Budget committees draft budget resolutions

House and Senate budget committees each write a budget resolution outlining the policies that the majority intends to implement in the coming fiscal year. These are identical measures this time around.

The budget committees must include what are known as "reconciliation instructions" inside their respective resolutions. These instructions tell specific committees to write reconciliation legislation by a certain date and to achieve a specific dollar amount of budgetary change in direct spending, revenue and/or deficit related to the policy at hand.

In the case of Biden's COVID-19 relief package, Democrats could use reconciliation for $1,400 stimulus checks, a $400 unemployment insurance boost, $170 billion to aid the reopening of schools and a $15 per hour minimum wage, among other measures.

Per the Congressional Budget Act, no more than three measures can qualify for expedited reconciliation procedures in the Senate -- one each for direct spending, revenue and the debt limit.

Key players in this step would be Senate Budget Committee Chairman Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., and House Budget Committee Chairman John Yarmuth, D-Ky.

On ABC's "This Week," Sanders told Co-anchor Martha Raddatz, "We all look forward to working with Republicans. But right now, this country faces an unprecedented set of crises."

"We have got to act and we have to act now," Sanders added on Sunday.

Step 2: Committees get to work on reconciliation instructions

Committees begin work on their reconciliation instructions. None are required to adhere to the policy recommendations from the budget committees. They are given wide discretion.

If the reconciliation instructions are to more than one committee, then the committees send their bills back to the budget committee, where that panel compiles everything into one omnibus piece of legislation.

Step 3: Floor consideration

Once a reconciliation measure has been reported out of the Budget Committee it is ready for consideration by the full chamber. It is also possible that Schumer calls up the bill directly on the floor, bypassing the committee process.

There is no filibustering of a reconciliation bill in the Senate. Debate is limited to 20 hours, with debate on any one specific amendment limited to two hours. Though, once the debate time expires, senators can still offer amendments during a period known as "vote-a-rama" -- which includes a short debate with 10-minute voting blocks. Technically, the rules allow for endless amendments, but in practice, there is usually a limit. Aides are indicating that perhaps a couple dozen could be voted on this time around.

Amendments must be relevant to the matter at hand -- in this case, coronavirus relief -- under what's known as the "Byrd rule."

Any senator may raise a point of order during consideration of a reconciliation bill against measures that are considered extraneous. If the point of order is sustained by the presiding officer, then the offending provision or amendment is stricken unless its proponent can muster a three-fifths (60) Senate majority vote to waive the rule.

In the House, the duration of debate has historically been one to three hours. The number of amendments has always been strictly limited, according to the Congressional Research Service.

The bills that pass out of each chamber must be identical and any differences must be resolved before moving on.

Step 4: Presidential action

The bill is then sent to the president, who can sign or veto it. Congress can override the veto if both chambers vote by a two-thirds supermajority.

Since its first use in 1980, reconciliation legislation has been vetoed just four times -- three times by former President Bill Clinton and once by former President Barack Obama. Those vetoes were not overridden.

ABC News' Molly Nagle and Allison Pecorin contributed to this report.