Clinton campaign lawyer found not guilty on charge of lying to FBI in loss for Durham

It was the first in-court test of Durham's investigation of the Russia probe.

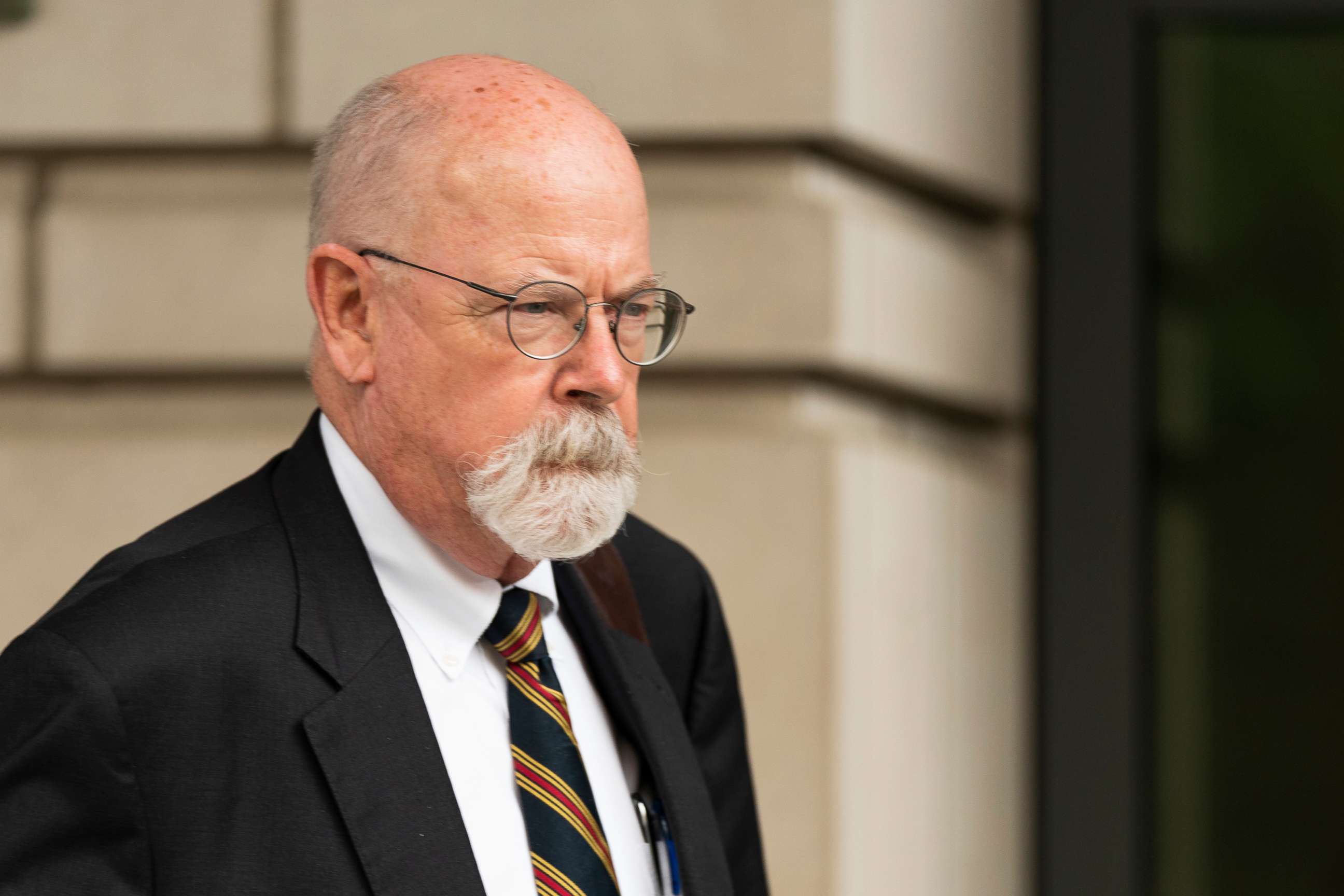

A Democrat-linked lawyer charged by Special Counsel John Durham with lying to the FBI in 2016 was found not guilty a federal jury in Washington on Tuesday following a nearly two-week trial that served as the first in-court test of Durham's more than three-year investigation into the Russia probe.

Michael Sussmann was charged by Durham last year for allegedly bringing forward a tip to a senior FBI official in September 2016 about a potential connection between computer servers for then-presidential candidate Donald Trump's company and Russia's Alfa bank -- and lying about who he was representing at the time.

"While we are disappointed in the outcome, we respect the jury's decision and thank them for their service. I also want to recognize and thank the investigators and the prosecution team for their dedicated efforts in seeking truth and justice in this case," Durham said in a statement.

"I told the truth to the FBI and the jury clearly recognized that with their unanimous verdict today," Sussmann said outside the courthouse following the verdict. "Despite being falsely accused, I'm relieved that justice ultimately prevailed in my case."

Through multiple days of witness testimony and evidence exhibits displayed in the D.C. district court, Durham's prosecutors sought to convince the jury that Sussmann brought the info to then-FBI general counsel James Baker as part of Sussmann's work for Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign and a technology company executive who had worked on assembling the data.

"He knew that if he told Mr. Baker that he was there on behalf of the Clinton campaign, the chances of the FBI investigating would be diminished," assistant special counsel Jon Algor said Friday in closing arguments.

They alleged that Sussmann set up the meeting with the hope of generating an "October surprise," to leak that the FBI was investigating a potentially suspicious tie between Trump's campaign and Russia at a time when Russia was carrying out its hack-and-dump campaign against the Democrats.

While Sussmann's attorneys acknowledged that he was at the time representing Clinton's campaign and a tech executive named Rodney Joffe in handling the allegations, they claimed Sussmann's intention in setting up the meeting with Baker was to alert the FBI to what he believed was concerning information and notify them that major news outlets were also pursuing it as a story.

In their closing argument Friday, Sussmann's attorney Sean Berkowitz accused Durham's team of pushing baseless "political conspiracy theories" through their prosecution of Sussmann, who he said brought forth the information to Baker in genuine good faith.

As a result of Sussmann's meeting with Baker, according to his attorneys, the FBI was able to convince the New York Times to hold off on reporting the Alfa Bank allegations while investigators evaluated the data -- which they quickly determined showed nothing nefarious. When the Times did eventually report on the Alfa Bank matter, it was part of a pre-election piece with the headline, 'Investigating Trump, FBI Sees No Clear Link To Russia.'

"The meeting ... is the exact opposite of what the Clinton campaign would have wanted," Sussmann's attorney Michael Bosworth said last week.

The two-week trial featured testimony from a host of current and former law enforcement officials as well as former key figures in Clinton's campaign.

While the charge leveled against Sussmann was narrow, in the months since his indictment Durham used the case to bring forward other evidence that prosecutors suggested showed a broader conspiracy, alleging Clinton's campaign and other political operatives sought to gin up and spread false accusations to smear Trump and use the nation's law enforcement agencies as political tools.

But Marc Elias, the Clinton campaign's former general counsel, and Robby Mook, the campaign's manager, testified there was no discussion in the highest levels of the campaign about ordering or authorizing anyone to bring the Alfa Bank allegations directly to the FBI.

While Mook acknowledged that Clinton herself at one point signed off on disseminating the unverified allegations to the press so journalists could "vet" and report them out, he sought to throw cold water on the that the campaign believed it would have benefited from getting the FBI involved.

"Going to the FBI does not seem like an effective way to get information out to the public," Mook said.

Mook said that after Clinton authorized sending the Alfa Bank data out to journalists, a press official -- not Sussmann -- was tasked with pushing it out to reporters. A report on the allegations was later published by Slate days before the election, though it made no mention of the FBI's investigation into the data.

Sussmann's attorneys also focused their strategy around undercutting testimony from the government's star witness, Baker, who said under questioning from the special counsel's office last week that he was "100% confident" that Sussmann told him in their Sep. 19 meeting he was not there on behalf of a particular client.

That testimony, Sussmann's attorneys noted, directly conflicted with past statements Baker had made in interviews under oath with congressional investigators and the DOJ's inspector general -- where he either said that he believed Sussmann was there on behalf of unnamed cybersecurity experts or didn't remember if Sussmann had mentioned representing clients one way or another.

But prosecutors also entered evidence this week showing that Sussmann had billed several flash drives he purchased days before the meeting to the Clinton campaign -- two of which Durham says Sussmann provided to Baker in their meeting that included the unverified data purporting to show a connection between Trump and Alfa bank.

Additionally, they flagged multiple hours of time entries Sussmann had billed to the Clinton Campaign and the tech executive Rodney Joffe leading up to and after the meeting with Baker, where he wrote he was working on 'confidential' issues that Durham says was in reference to the Trump-Alfa bank allegations.

"If an opponent had brought this information, [the FBI] would want to know more about it," Algor said. "They would question the credibility of the source and whether the FBI was being used -- being played by politics."

In the three years since Durham was initially assigned to look into the origins of the Russia investigation, he has secured one guilty plea of a former lawyer with the FBI who admitted to doctoring an email that was used to support a surveillance application that targeted a former Trump campaign aide.

The only other indictment brought by Durham outside of Sussmann was against Igor Danchenko, a lead analyst who contributed to the now-infamous Steele Dossier, who was charged last year with five counts of lying to the FBI about who his sources were for claims in the dossier. Danchenko has pleaded not guilty to all counts and his case is set for trial in Virginia in the fall.

The FBI's investigation into Russia's interference in the 2016 election was not launched as a result of the Alfa Bank allegations or the Steele Dossier, and neither eventually factored into findings released by special counsel Robert Mueller following his two-year investigation. While Mueller's probe found numerous instances of contacts between Trump campaign officials and individuals with ties to Russia's government, he determined evidence didn't support charging any individuals of engaging in a criminal conspiracy with Russia.