'A Cloak for Discrimination': Trump order reminds Asian-Americans of laws against them

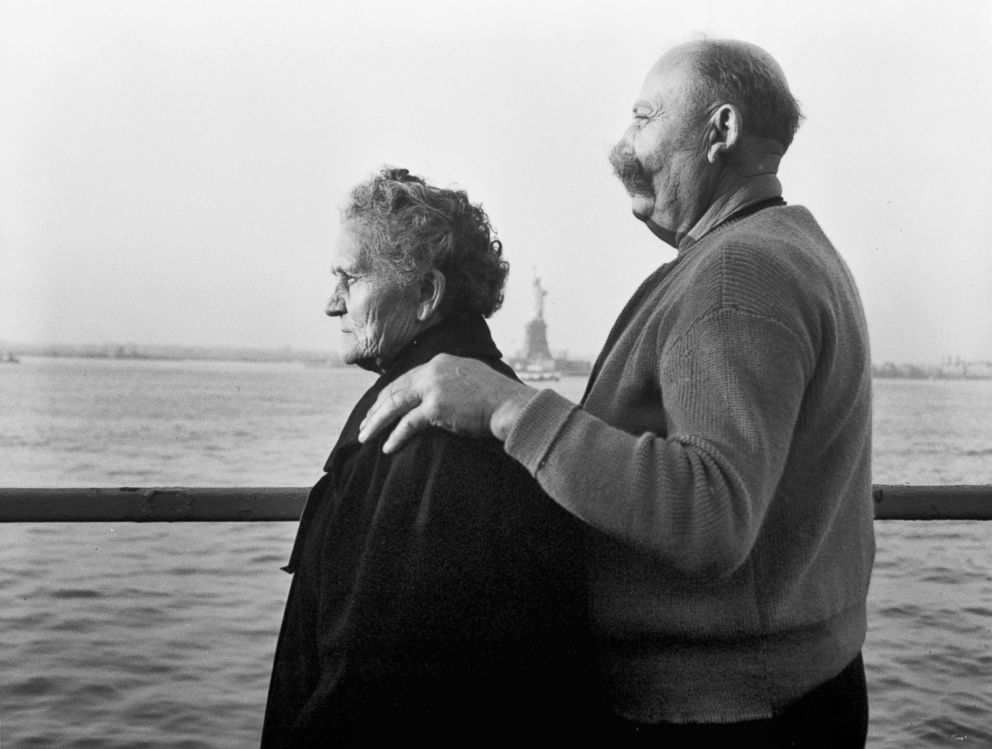

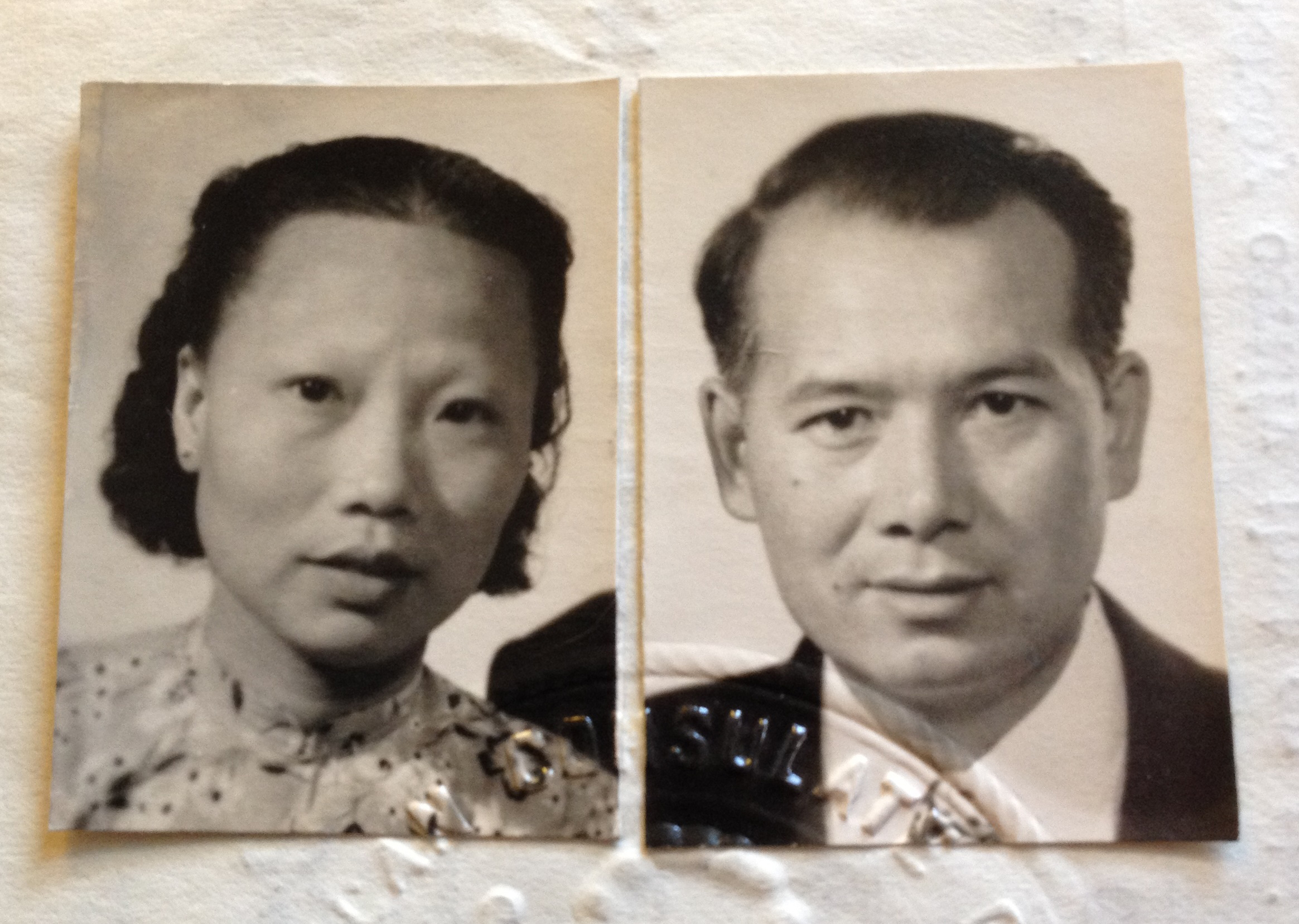

Nick Lee's grandfather was separated from his wife for 16 years.

— -- President Trump’s controversial immigration order has played out on the national stage with protests, court rulings and now a promise by the president to replace the travel ban. But for Nick Lee, it's personal -- a painful reminder of his family's history.

Lee's grandfather was separated for 16 years from his wife and never got to see his first child before she died -- all because of the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first major U.S. law restricting who could come into the country.

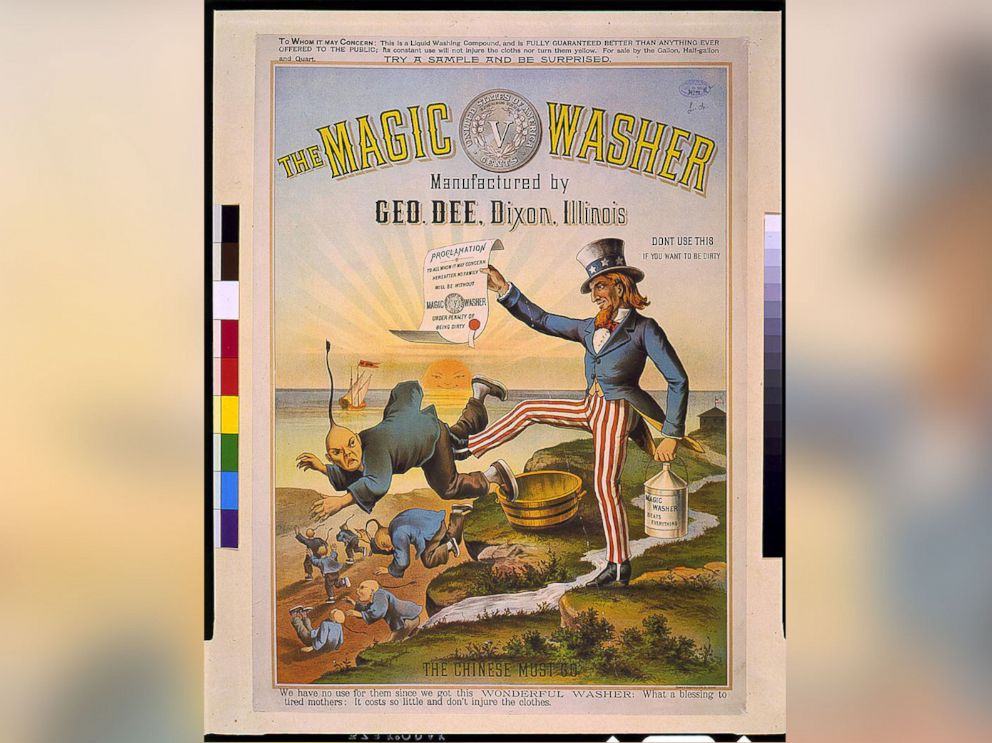

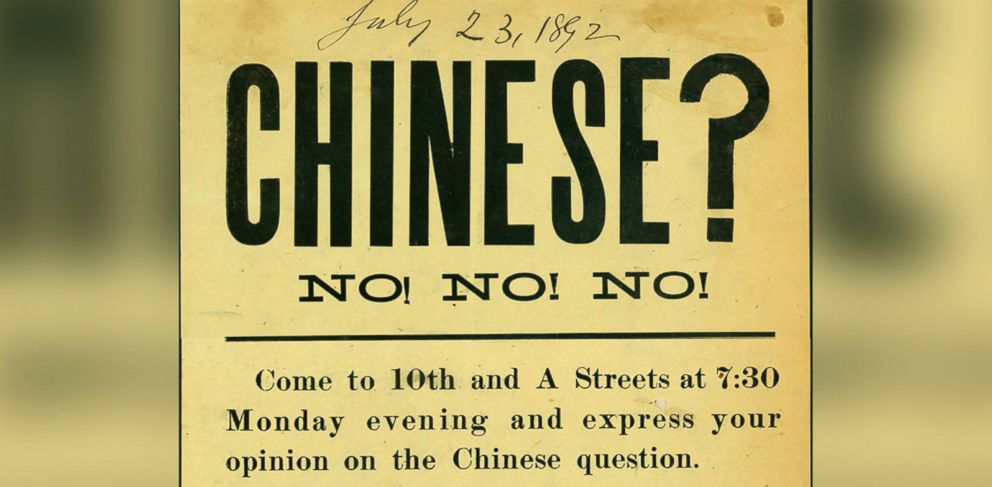

The 1882 law -- followed by other exclusion acts that stayed in force for six decades -- was born amid a wave of fear that Chinese workers who had come during the Gold Rush and helped build the United States’ railroads were competing with other Americans for jobs and lowering wages.

"They used to say that the Chinese are outsiders, and they couldn’t mix with our society, just like what they’re saying about Muslims now,” said Lee, who works for OCA-Asian Pacific American Advocates, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy organization.

Lee said he fears that Trump's executive actions will separate families in the same way as his.

"It's horrifying," he said. "There's no other word for it."

Trump's travel ban

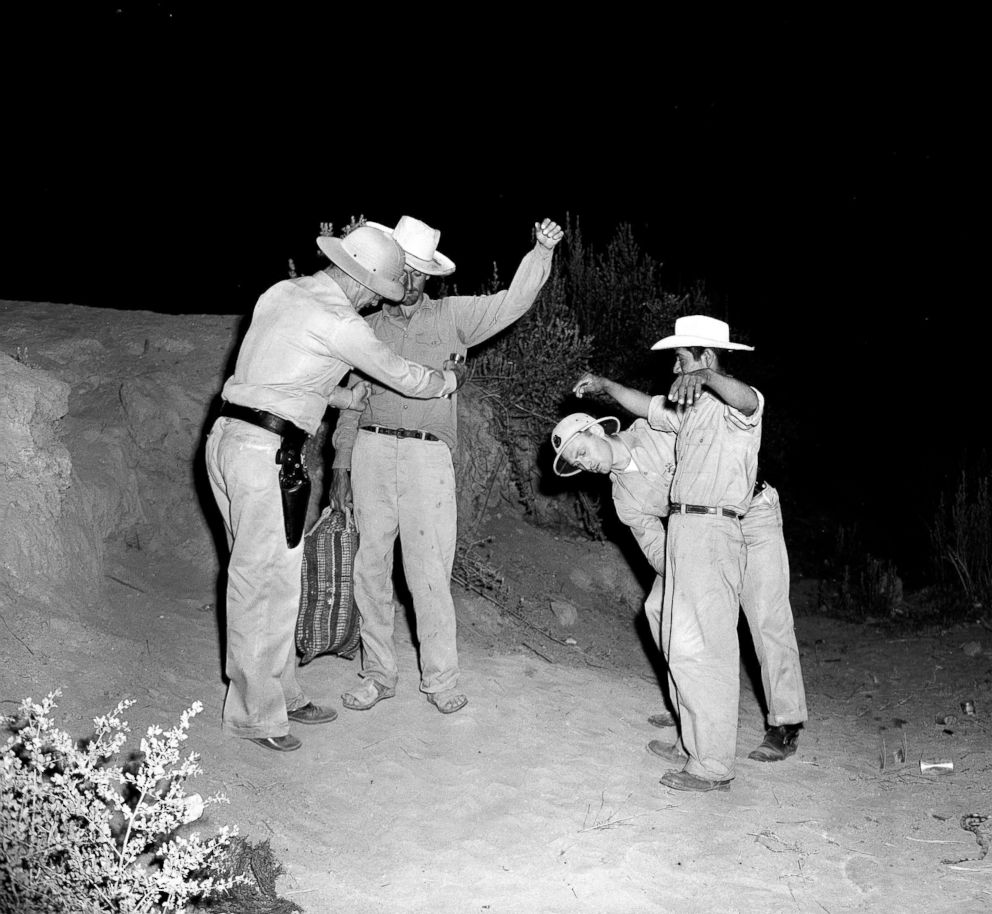

The president said Thursday that he will issue a new executive action soon following a federal court's putting a hold on the order signed Jan. 25. That order bans entry into the U.S. of people from seven Muslim-majority countries for 90 days, suspends refugee admissions from any country for 120 days and indefinitely bans the entry of Syrian refugees.

The president said executive action is necesssary to bolster national security and that the seven countries -- Iraq, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and terrorism.htm" id="ramplink_Yemen_" target="_blank">Yemen -- were identified by the Obama administration as a concern because of their history of links to terrorism. Critics said the order is a de facto Muslim ban.

Within hours after it was signed, scores of people coming to the U.S. were detained at airports around the country. Families were separated as members trying to join loved ones in the U.S. were stopped. And 60,000 visas were cancelled in one week before a federal judge stayed the order on Feb. 3.

'I wanted to live, so I had to come to America’

The president's immigration order also brought up painful reminders for Erika Lee.

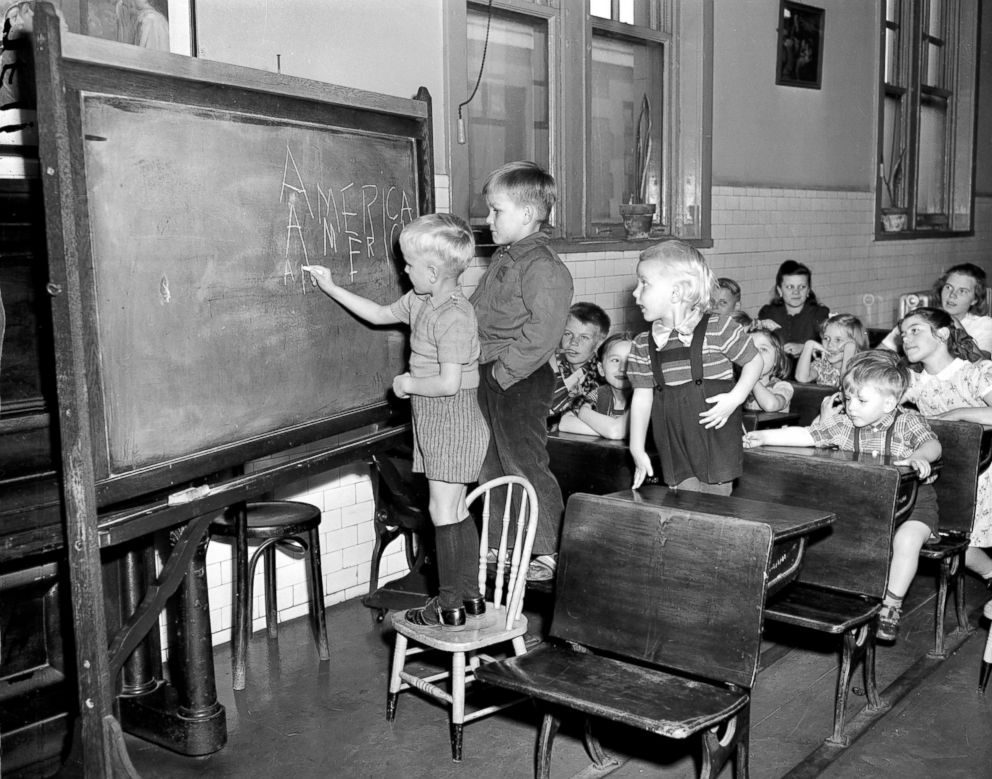

Her grandfather came to the U.S. in 1918 as an orphan under a fake identity, what was called "a paper son," with documents falsely stating he was related to American citizens.

“He had to give up his name and become someone else.” said Erika Lee, a history professor at the University of Minnesota and the author of books on immigration including, "At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration During the Exclusion Era, 1882-1943," and who is not related to Nick Lee.

She said her grandfather felt he had no choice.

“I remember my grandfather saying ‘I wanted to live, so I had to come to America,’" she said. In China, "if you wanted to live during that time you went abroad.”

Political and economic instability in China from around the 1850s on led thousands to immigrate to the U.S. in search of opportunity and a better life, according to the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute in Washington, D.C.

America's complicated history with immigration

Erika Lee said the president's travel ban reminds her of old U.S. laws restricted Chinese immigration -- presented as for the "public good" and "national security" when really such laws are "a cloak for discrimination,” she said.

“It pains me and frustrates me to no end to realize we are repeating the mistakes of the past,” Erika Lee said of the president's executive order, “repeating laws that our presidents and government have regretted and regarded as a historic mistake.”

American Citizens Put in Camps

Chinese Americans weren’t the only groups targeted by past immigration laws. The Johnson-Reed Act signed in 1924 set immigration quotas based on national origin and completely barred all Asians.

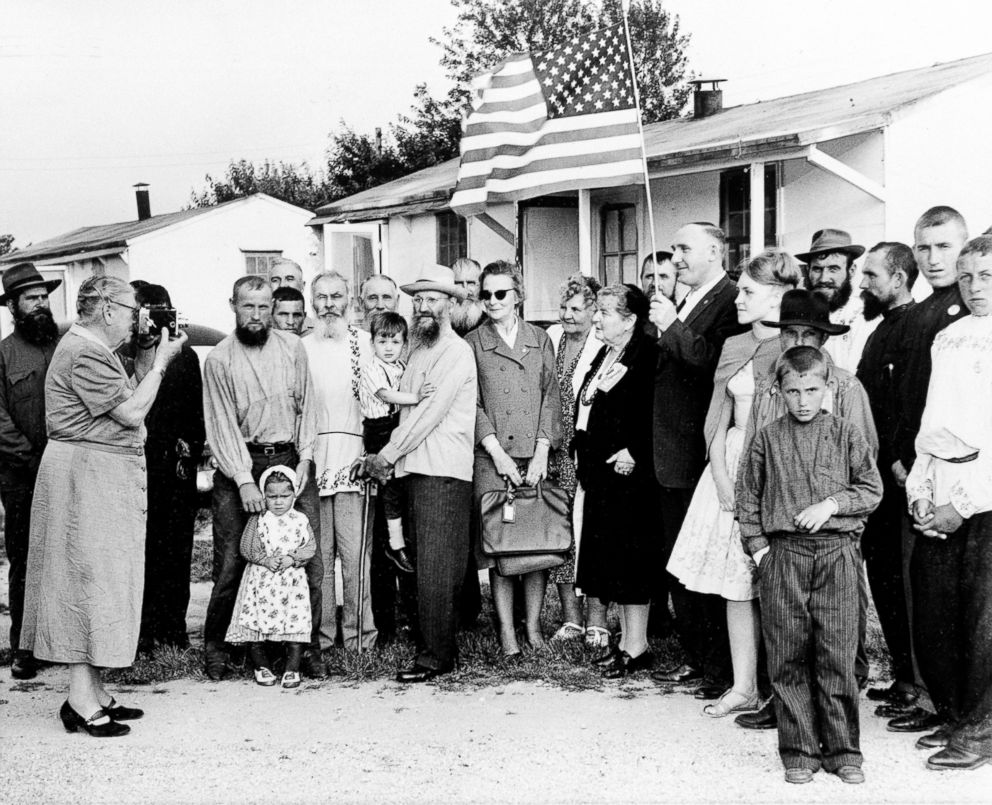

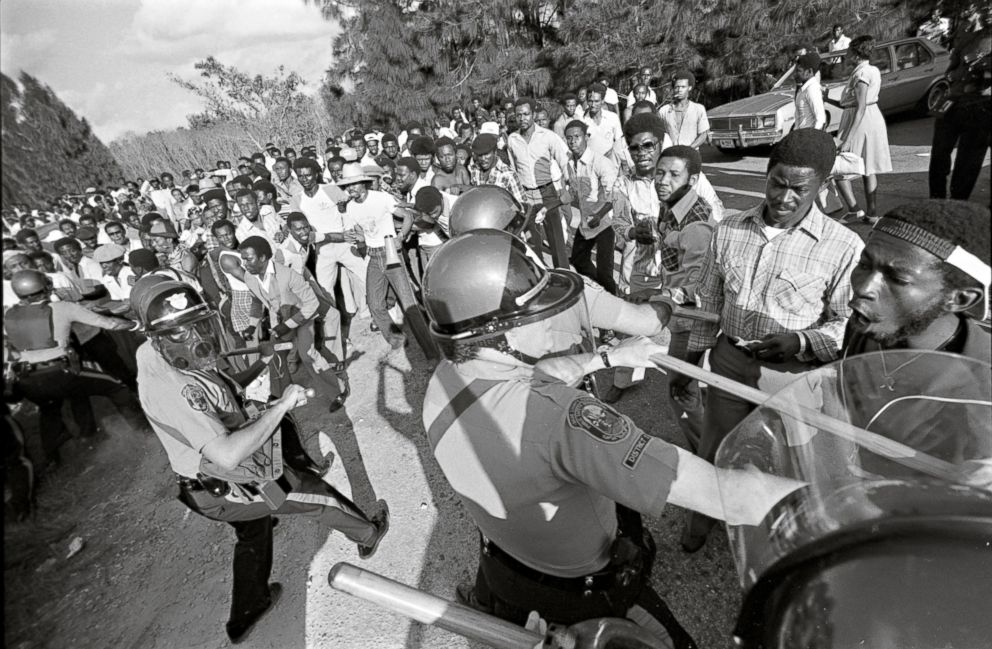

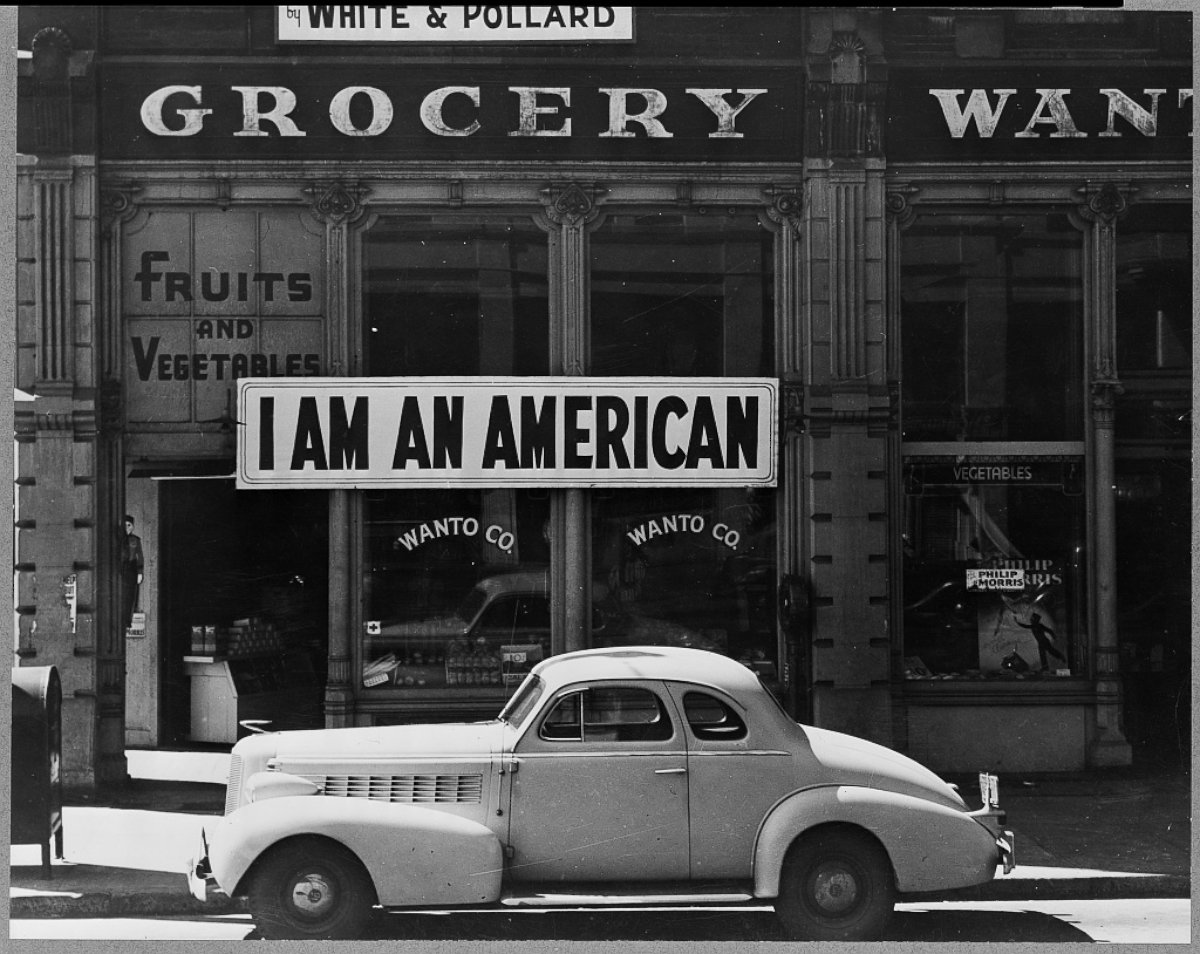

Then in 1942, after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor the previous December, President Roosevelt signed an executive order that led to 120,000 Japanese-Americans, many of them American citizens, being forced into internment camps for the duration of World War II. President Reagan formally apologized for the policy in 1988.

Satsuki Ina was born behind barbed wire 73 years ago in the Tule Lake internment camp in California.

Ina, a psychotherapist who has produced documentaries on the internment camps, said her parents were born in America but because they were educated in Japan, they were deemed high-risk. They were forced to renounce their American citizenship and separated into different camps, she said. Her father was sent to a camp in North Dakota.

After her parents was released, she said: "They didn’t talk about it at all.”

Then while she was in college amid the U.S. Civil Rights movement, she said realized what her parents went through.

“I went home to find out why they were anxious about these protests," Ina said. "That’s when they told me about their renunciation of their citizenship.”

"I was shocked, but proud. When I asked why they never told us, they said they were afraid I’d be ashamed of them,” she said. “My parents were innocent, just like the other 120,000 Japanese Americans. It was an act of racism that put them in the camps. They felt vulnerable for the rest of their lives, scared their freedom would be stripped away once more."

Now with the president's immigration order, Ina said: “We see the same sentiment and language about risks to national security, about blanket actions taken based on fear.”

A Father's Sacrifice, a Son's Success

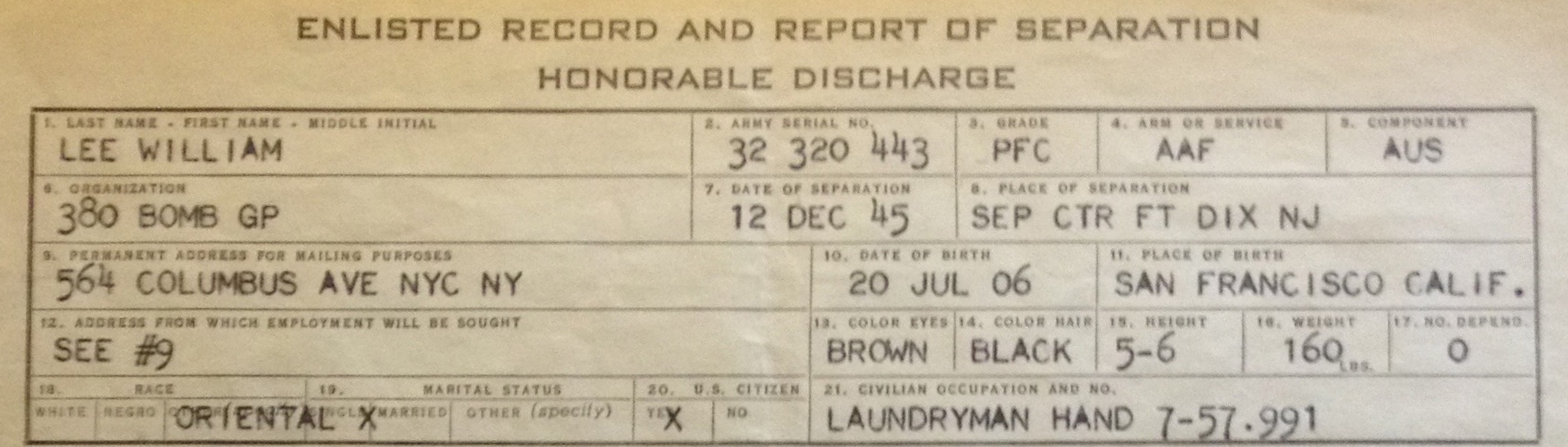

Nick Lee, the Asian-American advocate whose grandfather, William, was long separated from his wife, came into the U.S. illegally through Canada around 1930.

He was 24 and penniless but wound up working in the laundry business in New York.

Finally, after he served in the U.S. Army in World War II, William Lee's wife was able to join him in his new country.

They had two sons in the U.S. One, Nick's father, Bill Lann Lee, rose to become assistant U.S. Attorney General for Civil Rights under President Bill Clinton.

To Nick Lee, that progression is America's strength.

“In one generation, you have my grandfather who came as an undocumented immigrant to my father, one of the highest-ranking Asian-Americans in government at his time."

Ina, like Nick Lee, said she will fight against any new immigration laws that she sees as discriminatory.Americans can't take civil liberties for granted, Ina said.

“The Constitution is a piece of paper,” Ina said. “It’s the people that bring it to life.”