Conflicts between Sondland, other witnesses in impeachment probe raise questions

Gordon Sondland is the U.S. Ambassador to the EU and a Trump megadonor.

New accounts from key witnesses in the impeachment investigation on Capitol Hill have raised questions about the testimony of Gordon Sondland, the U.S. ambassador to the European Union and a Trump megadonor.

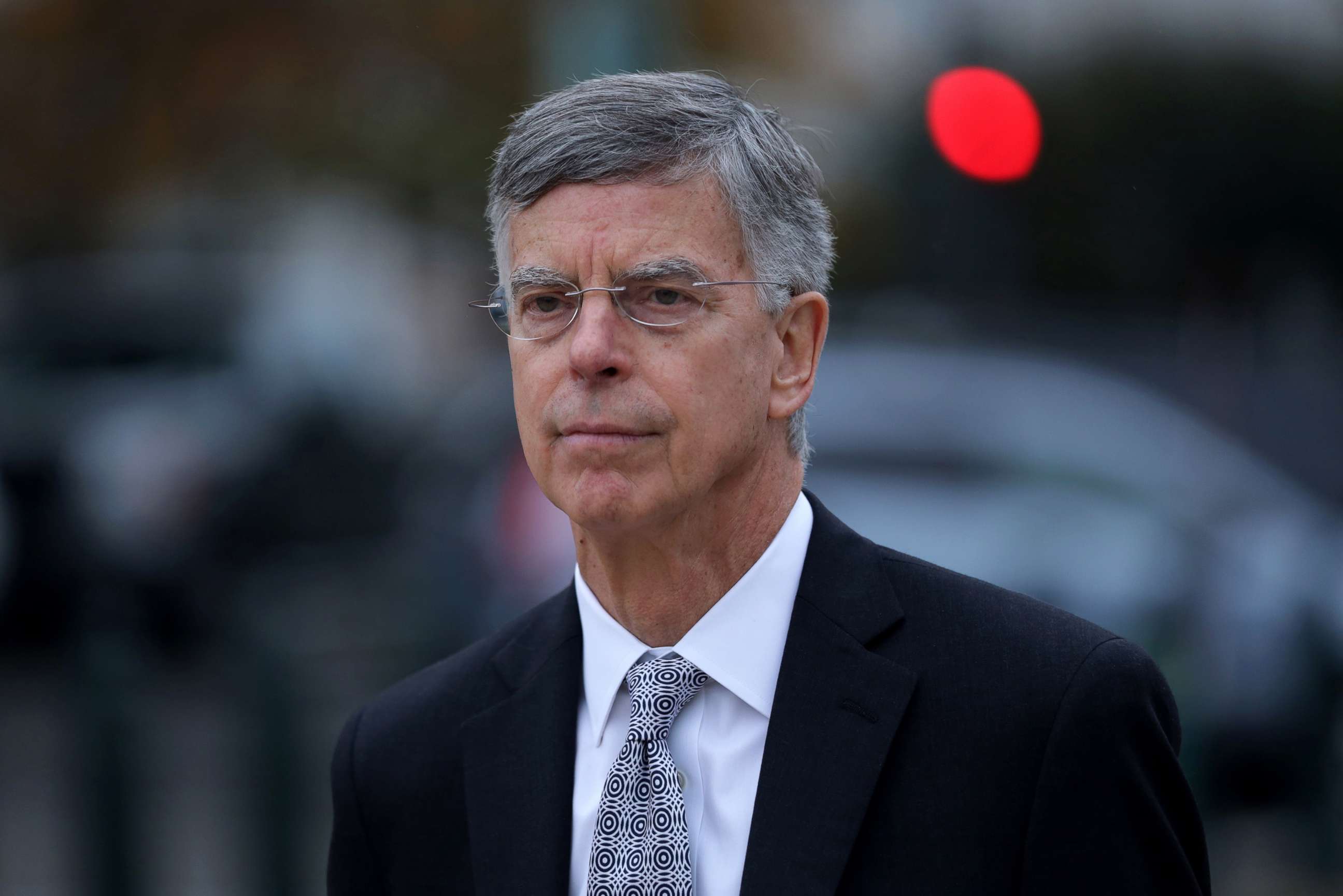

Specifically, Democratic lawmakers are comparing Sondland's account of events at the center of the Ukraine impeachment inquiry with those of William Taylor, the top U.S. diplomat in Ukraine, and Army Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman, the National Security Council's Ukraine expert.

"We have a number of witnesses who have told one version of events," Rep. Eric Swalwell, D-Calif., said of the testimonies.

"That's in contrast with what Ambassador Sondland said," Swalwell recounted recently, adding that he would reserve judgment about the truthfulness of the witnesses until the investigation is complete.

While the hearings took place behind closed doors, making it impossible to know what exactly was said, an ABC News examination of opening statements made public found key differences between Sondland's prepared testimony and that of Taylor and Vindman:

The July 10 meeting

Both Vindman and Sondland attended the same July 10 meeting in Washington but told Congress conflicting stories about what occurred during and after.

According to Vindman's opening statement to lawmakers Tuesday, obtained by ABC News, he testified that during a July meeting with a Ukrainian official that he and Sondland both attended, Sondland "started to speak about [Ukraine] delivering certain investigations in order to secure a meeting with the president." During a scheduled debriefing following that meeting, Vindman said Sondland went on to emphasize "the importance that Ukraine deliver the investigations into the 2016 election, the Bidens, and Burisma"—a Ukrainian energy company on whose board former Vice President Joe Biden's son, Hunter Biden, served at the time.

Vindman said he told Sondland his comments "were inappropriate" and reported the incident to the NSC's lead lawyer.

Sondland, who testified on Capitol Hill earlier this month, told lawmakers that while President Donald Trump directed him to work with his personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani to push Ukraine to announce investigations, he "did not understand, until much later, that Mr. Giuliani's agenda might have also included an effort to prompt the Ukrainians to investigate Vice President Biden or his son or to involve Ukrainians, directly or indirectly, in the President's 2020 reelection campaign," according to his opening statement obtained by ABC News.

Following that July meeting, Sondland said no one on the National Security Council staff "ever expressed any concerns to me about our efforts" or "any concerns that we were acting improperly."

Links between the Bidens and Bursima, foreign aid and investigations

Taylor's opening statement asserted Sondland knew more about the political motivations tied to the withholding of military aid to Ukraine than he told Congress. But Sondland also testified that he was unaware or any quid pro quo at play. He also claimed not to be aware of any connection between Hunter Biden and Burisma until recently.

"Although Mr. Giuliani did mention the name "Burisma" in August 2019, I understood that Burisma was one of many examples of Ukrainian companies run by oligarchs and lacking the type of corporate governance structures found in Western companies," Sondland claimed. "I did not know until more recent press reports that Hunter Biden was on the board of Burisma."

Taylor, in his opening statement to House impeachment investigators, said in September a National Security Council official informed him about a phone call between Sondland and an assistant to Ukraine's president, during which Sondland allegedly said "security assistance money would not come until President Zelenskiy committed to pursue the Burisma investigation."

Taylor said that when he confronted Sondland about the conversation, Sondland said the release of the aid was dependent on Zelenskiy making such an announcement, and that "President Trump wanted President Zelenskiy "in a public box" by making a public statement about ordering such investigations."

But Sondland claims he took Taylor's concerns about a perceived link between the aid and the investigations back to the president, and that after they spoke he called Trump, who told him there was "no quid pro quo" with Ukraine multiple times.

"Let me state clearly," Sondland's statement reads. "Inviting a foreign government to undertake investigations for the purpose of influencing an upcoming U.S. election would be wrong. Withholding foreign aid in order to pressure a foreign government to take such steps would be wrong. I did not and would not ever participate in such undertakings."

An invitation to the Oval Office

Both Taylor and Vindman asserted that Sondland took part in efforts to leverage a White House visit with President Trump in exchange for Ukraine committing to specific investigations into the president's political rivals. However, Sondland said he wanted the two leaders to meet in Washington, regardless of Ukraine's commitment to pursuing any investigations.

Sondland told Congress he believed "a White House meeting between Presidents Trump and Zelenskiy was important" and "should be scheduled promptly and without any pre-conditions."

An attorney for Sondland declined to comment for this story.

Sondland appeared on Capitol Hill again Monday to review his testimony, according to two sources familiar with the matter, a courtesy usually granted to all witnesses.

What lawmakers will do with testimony they believe conflicts with other accounts remains to be seen. House Democrats could pursue perjury charges against Sondland or simply call for further investigation into the matter, including requesting that Sondland return for additional questioning.

Two key federal statutes prohibit lying to Congress--U.S. Code Section 1621 says anyone who "willfully and contrary to such oath states or subscribes any material matter which he does not believe to be true" is guilty of committing perjury, while Section 1001 similarly outlines what constitutes perjury, but also applies to those who are not under oath. But perjury is a rarely prosecuted crime with a high legal bar difficult to meet especially when dealing with conflicting recollections of events without a written record or other factual evidence. The law stipulates that a prosecutor must show that the person charged with the crime knew they were making a false statement during their testimony.

But Congress has made criminal referrals to the Justice Department for perjury. In April, House Intelligence Chairman Adam Schiff issued one for Blackwater founder Erik Prince, alleging that Prince "willing misled the committee" during his 2017 testimony in connection with Congress's investigation into Russian interference in the U.S. political process, listing six discrepancies between the Mueller report's findings and Prince's account. As of now, that referral has not resulted in any charges against Prince.

Special counsel Robert Mueller did charge two individuals with perjury: longtime Trump associate Roger Stone, whose indictment includes five counts of making false statements to Congress, and Trump's former personal lawyer Michael Cohen, who pleaded guilty to lying to Congress. Stone has pleaded not guilty and is awaiting trial, and Cohen is currently serving a three-year prison term for perjury as well as financial crimes he admitted to in federal court.