Empathy elusive, Trump chooses economic cheerleader role over 'comforter in chief'

Historians say he has eschewed a president's traditional role.

President Donald Trump has largely focused on the economic impact of the coronavirus crisis, even more so as of late, frequently meeting with and calling business executives, rather than victims, their relatives or health care workers fighting COVID-19 on the front lines.

His expressions of empathy have come few and far between, punctuating his passionate promises of economic redemption and attacks on his political opponents.

Even as the U.S. death toll last week surpassed that of the Vietnam War, Trump has continued to eschew the president's traditional role as "comforter in chief."

That's why it was so unusual this week when, after months of forgoing significant personal outreach to the tens of thousands of American families who have lost loved ones, he went beyond his typical scripted condolences.

"I love you," Trump said, when asked Tuesday by ABC News' "World News Tonight" anchor David Muir what he wanted to say to those families. "We're with you," he added. "We're working with you. We're supplying vast amounts of money, like never before."

He often turns to talking -- about himself.

"The word empathy is not in his vocabulary," presidential historian Ted Widmer, a professor at the City University of New York's Macaulay Honors College, told ABC News. "You can't be empathetic and always talk about yourself. The two things cancel each other out."

In times of crisis, American presidents have typically served as national patriarchs of sorts, holding emotional meetings with victims of disasters, terrorism and wars, and using soaring rhetoric to heal the country and propel Americans forward.

But Trump has yet to visit a hospital, and there have been few signs that he has interacted with people who have fallen ill. When he speaks about victims, he often quickly pivots to how he will help those hurting economically.

"To the people that have lost someone, there's nobody -- I don't sleep at night thinking about it," Trump told Muir Tuesday. "There's nobody that's taken it harder than me. But at the same time I have to get this enemy defeated. And that's what we're doing."

In mid-April, the president brought a group of Americans who had recovered from the virus to the White House, although he devoted a large portion of the gathering to promoting a drug treatment that has not actually been proven to help.

He hosted a group of nurses on Wednesday to mark National Nurses Day, signing a proclamation honoring them and saying they "answered the call of duty in America’s hour of need." But when one noted the supply of personal protective equipment had been "sporadic," he shot back, "Sporadic for you, but not sporadic for a lot of other people."

On Thursday, at a White House event marking the National Day of Prayer, in the White House Rose Garden, Trump said "we pray for every family stricken with grief and devastated with a tragic loss," as well as for health care workers, first responders, researchers and other front line workers.

Trump has spoken a few times about a friend in New York, real estate developer Stanley Chera, who died from COVID-19 last month, describing the harsh toll the virus had taken on him. He said Sunday he had "lost three friends," although he not give details of the others.

But in early April, he said Chera's diagnosis had not marked a turning point in his own thinking about the coronavirus.

'I have spoken to three, maybe I guess four families unrelated to me'

Asked by ABC News on April 28 whether he had spoken to the families of anyone who had lost a loved one to COVID-19, other than Chera, and if any of their stories had affected him, the president said he had talked with only a handful.

"I have many people. I know many stories," Trump said. "I have spoken to three, maybe I guess four families unrelated to me. I did. I lost a very good friend. I also lost three other friends, two of whom I didn't know as well, but they were friends and people I did business with."

Trump did not share details, describe any of their stories or say how the interactions had impacted him. Instead, he turned to discussing how he would like schools to reopen.

A White House spokesperson said that by "unrelated," the president meant "not his family but both people he has a connection to as well as some he didn’t know."

The official declined to share the names or details of those people or put ABC News in touch with them but cited an example of a man who knew Trump writing to him that his mother had fallen ill with COVID-19. Trump called the man, whose mother survived, in order "to express his concern and offer his personal encouragement and thoughts," the official said.

In late April, The Washington Post published an analysis of three weeks' worth of Trump's daily briefings on the coronavirus and found he had spent just 4 1/2 minutes -- out of more than 13 hours -- expressing condolences for victims. He devoted two hours to launching attacks and 45 minutes to praising himself and his administration, the Post found.

In the days that followed that report, Trump read from prepared remarks at the start of his public appearances about the toll the virus has taken on victims. "We grieve by their side as one family," he said on April 27.

Three days later, asked if he would lower the flag at the White House, Trump said, "I don't think anybody can feel any worse than I do about all of the death and destruction that is so needless."

'That's just not part of who he is'

While Trump has avoided much interaction with victims of the coronavirus, he has over the course of his time in office traveled to disaster zones and met with shooting survivors.

The president has also made several trips to Dover Air Force Base in Delaware to honor the returning remains of service members, describing it as the "most unpleasant thing I do."

He has spoken about how difficult it is to sign letters to the relatives of deceased service members. "It's the hardest thing I have to do in this job," he said in October. "I hate it."

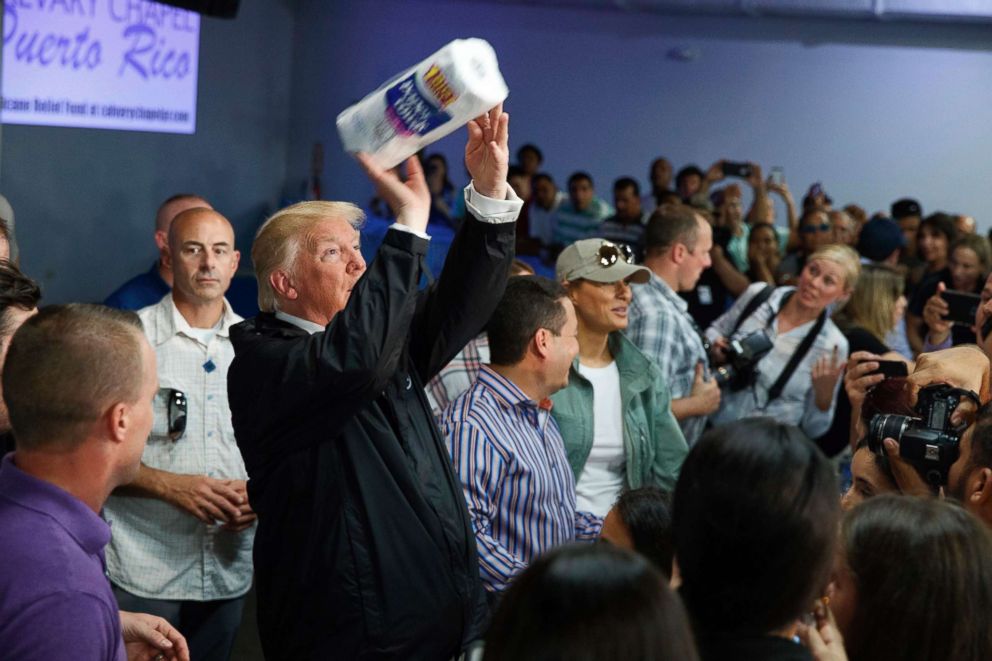

His visits to sites of tragedy have sometimes been clouded by controversy, such as when he smiled and flashed a thumbs up while posing with an orphaned baby after a shooting in El Paso, or when he enthusiastically tossed enthusiastically tossed rolls of paper towels into a crowd of Puerto Ricans after Hurricane Maria devastated their island.

"What it reminds me of is an awkward adolescent boy who's brought for the first time to a family funeral," presidential historian Barbara Perry told ABC News. "He doesn't know quite what to say, and the body language is odd."

Perry, a professor and director of presidential studies at the University of Virginia's Miller Center, said Trump seems to have "never learned how to be empathetic" and that his brash personality and style have failed to meet the needs of a crisis-stricken American public willing to give the president the benefit of the doubt.

"That's just not part of who he is," she said. "That's not how he got elected."

From Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address to Franklin D. Roosevelt's "fireside chats," presidents have long sought to bind the nation's wounds and give comfort, according to Perry.

That approach has accelerated in recent decades, with lofty speeches at times of national tragedy -- Ronald Reagan's remarks after the 1986 Space Shuttle Challenger disaster, or Bill Clinton's after the 1995 Oklahoma City Bombing -- and emotional encounters with victims.

"They're the symbolic representative of the entire American people," Widmer, a former adviser to Clinton, said. "They're the healer in chief, also, when something goes wrong."

Former President Barack Obama described meeting the parents of elementary school students gunned down in Newtown, Connecticut, in 2012, as the most difficult day of his presidency; he wiped away tears multiple times in the wake of that shooting. Several years later, Obama brought a community to its feet as he sang "Amazing Grace" during the eulogy for a pastor killed in a shooting at Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

Presidents other than Trump have taken flack for a perceived lack of sensitivity, too, such as when George W. Bush was roundly criticized in 2015 for flying over the Gulf Coast after Hurricane Katrina wreaked its havoc there.

Trump in recent months has missed an opportunity to unite Americans, perhaps with a visit to a hospital, or even his hometown of New York City, Widmer said.

"Americans want a healer, they really do," he said. "It's not partisan at that point. It's a people in pain. They want their president to, if not heal them, at least comfort them. And right now, we have a comfort deficit."