Inside the allegation that Bloomberg told a pregnant employee to ‘kill it’

“Kill it,” Bloomberg said, Sakai alleged in the complaint.

Mike Bloomberg had just finished taking a group photograph with a delegation of New York University students at Bloomberg LP headquarters when he struck up a conversation with Sekiko Sakai, one of the top-performing saleswomen of his namesake product, the Bloomberg Terminal.

"How's married life? Still married?" Bloomberg asked as the two walked to the cafeteria’s coffee station and filled their cups. Sakai said it was great and that she was pregnant, according to notes gathered by Sakai's lawyer as part of a 1995 complaint she later filed with state regulators against Bloomberg and his company.

"Kill it," Bloomberg said in a "serious monotone voice," Sakai alleged in the complaint.

"What? What did you just say?" Sakai said she asked. Bloomberg maintained eye contact and "repeated in a deliberate manner, 'kill it,'" she alleged. In the intervening years, Bloomberg has repeatedly denied saying it.

Sakai said that Bloomberg finished filling his coffee. As he put the lid on his cup, he mumbled to himself, "great, number 16." Sakai said she interpreted that to mean she was the 16th woman in the office to get pregnant. He walked away, she said in her complaint.

The alleged incident would have a resounding and residual effect on both parties in very different ways.

In the short term, Sakai said it damaged her. She claimed in her lawsuit that it was part of why she left the company -- sacrificing a lucrative paycheck and a job she said she loved -- and suffered serious psychological and physical health setbacks.

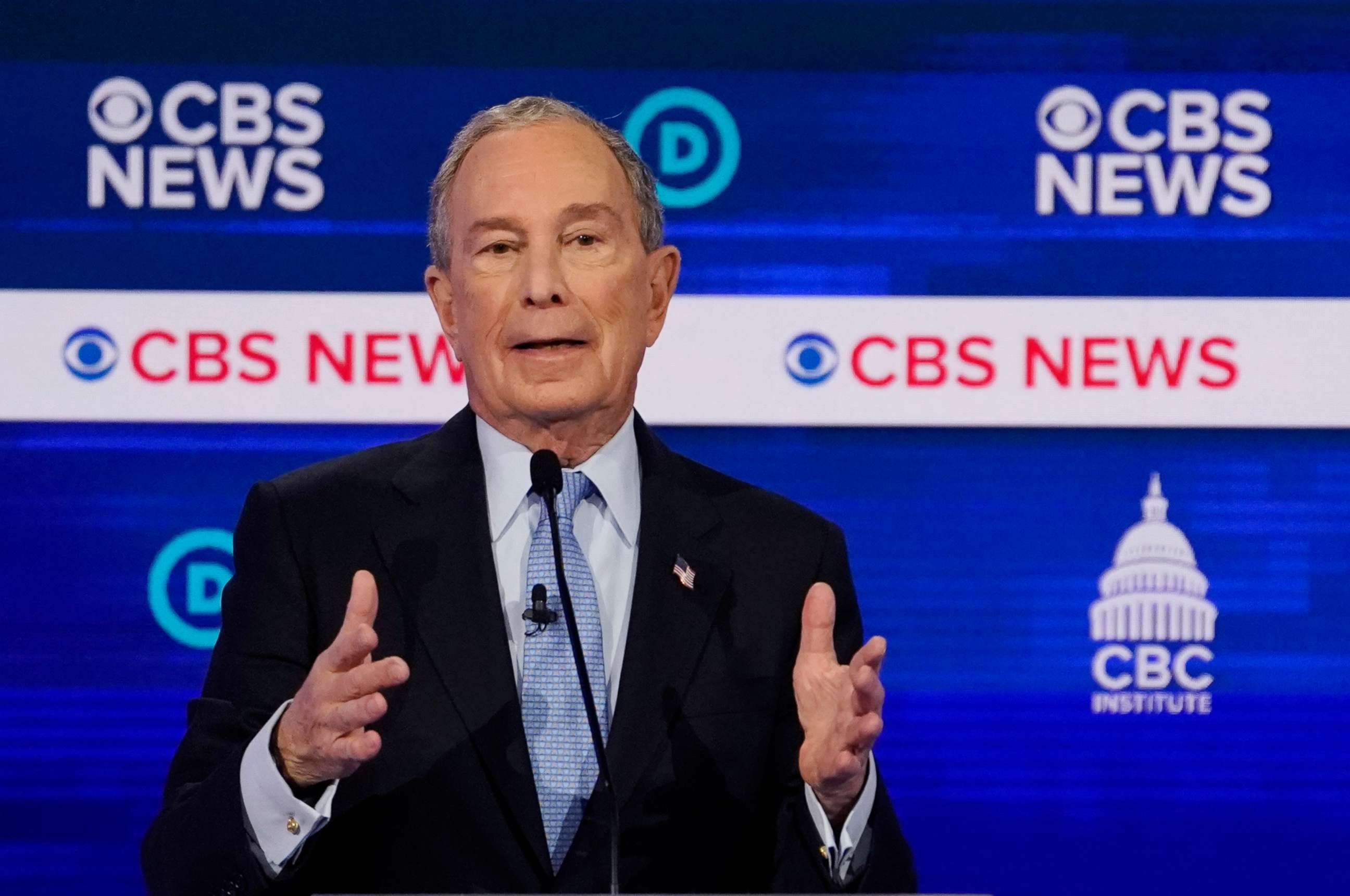

Now nearly 25 years on, it is Bloomberg who is feeling the impact of the alleged remark as he makes a run for the White House.

While his unusual campaign style – skipping early voting states and focusing his strategy on Super Tuesday -- has commandeered attention in the race for the Democratic nomination, so too have anecdotes about his past comments to and treatment of some women who worked for him. Allegations of inappropriate workplace comments and claims that the former New York City mayor's company became a hostile place for pregnant women, have both dogged the candidate on the campaign trail and onto the debate stage.

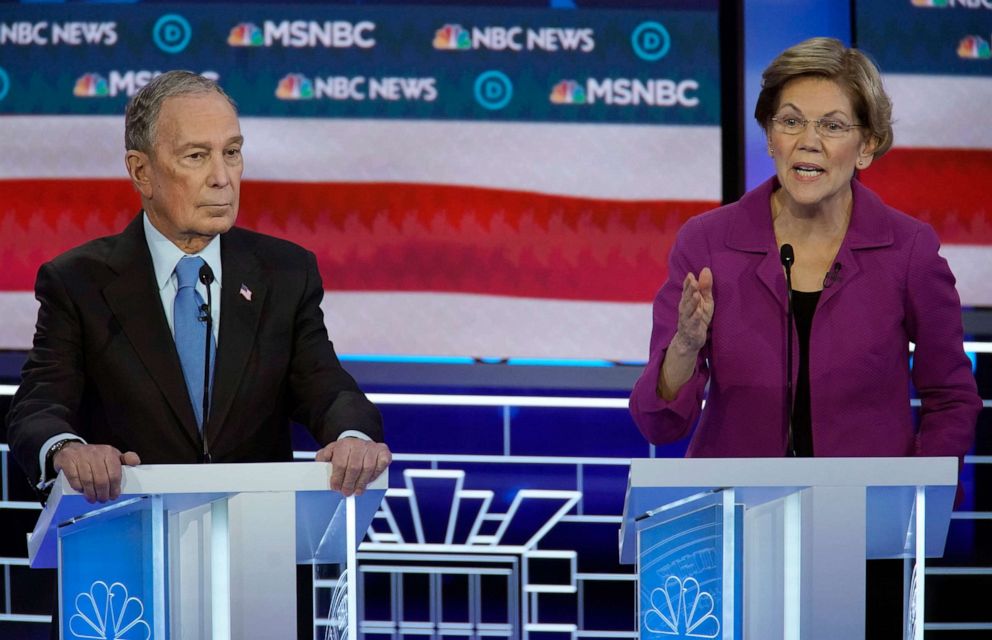

This week, rival Democratic candidate Sen. Elizabeth Warren – his fiercest critic among the field of candidates – confronted him over the alleged "kill it" comment.

"At least I didn't have a boss who said to me, 'kill it,' the way Mayor Bloomberg is alleged to have said to one of his pregnant employees," Warren said at Tuesday's debate in South Carolina.

Bloomberg's response has been firm and unbending – he has denied ever saying "kill it."

"I never said it. Period, end of story. Categorically, never said it," Bloomberg said Tuesday. "When I was accused of doing it we couldn't figure out what she was talking about."

His denials could face a new test in the coming weeks.

Sources have confirmed to ABC News that Sakai is one of three former employees whom Bloomberg's company has identified as having been restricted by a non-disclosure agreement from speaking about her claims of inappropriate comments by Bloomberg. But Bloomberg agreed to lift those restrictions in a recent turnabout.

Whether or not she speaks, transcripts of phone calls with co-workers made by Sakai and other materials used to craft her complaint with the New York State Division of Human Rights cast doubt on Bloomberg's denials. The documents, obtained by ABC News, indicate that Sakai tried desperately in the weeks that followed to sound the alarm on what her boss allegedly said.

Sakai said she alerted "ten people within the firm, five of whom were managers," according to the complaint filed with the New York Division of Human Rights, which she filed before her lawsuit. She told friends about the alleged interaction and described her mental and physical deterioration as a result of stress.

"I haven't slept at all, I got two hours of sleep and I'm not able to go to work. … I've lost ten pounds," Sakai told a friend two weeks after the incident, according to Sakai's transcript from the call.

In that complaint, Sakai said, as she was still pregnant, her doctor told her, "even if you are losing weight, if you are eating – which I am – as far as the baby is concerned, it should be getting nutrients it needs … she said it is not good because it is from a lot of stress."

Sakai hired a lawyer shortly thereafter and filed the complaint with the New York State Division of Human Rights in August of 1995. She later filed a lawsuit against Bloomberg and his company – which settled out of court – and even wrote to a U.S. Congresswoman, according to the documents obtained by ABC News.

"The words which were spoken to me by the CEO of my company on April 11, 1995 should never be heard by an expectant mother awaiting the birth of her first child," Sakai wrote in an undated letter addressed to Rep. Sue Kelly, R-N.Y. "I understand you are a strong advocate of women's issues and worker rights. I ask for your assistance to monitor my dispute in a timely and constructive manner."

The materials gathered by Sakai's attorney as part of their administrative complaint indicate Bloomberg dispatched senior aides at the company to call Sakai and feel her out. When all else failed, Bloomberg called her directly, she alleged. In notes that Sakai's lawyer said Sakai took from a voicemail he left, Bloomberg allegedly said, "I apologize if there was something you heard but I didn't say it, didn't mean it, didn't say it ... and whatever."

Regardless of whether Bloomberg told Sakai to "kill it," the comment is in line with other remarks attributed to Bloomberg from the time, according to transcripts of phone calls gathered by Sakai in which some Bloomberg LP colleagues allegedly recounted their own stories about the man at the top.

"Well, I started crying when (Bloomberg) said 'all it (a baby) does is eats and sh**s,'" a friend told her in late April 1995 of her own experience of telling Bloomberg she was pregnant.

Sakai replied, "That's how I feel … (Bloomberg) said some really demeaning humiliating things to me, but that was me, not my unborn child."

In many of those calls, according to the transcripts, Sakai encouraged others to come forward with their stories, but was repeatedly told the risks were too high.

"It's just a lot more complicated than just right vs. wrong for me," one colleague told her, according to the transcripts.

"I understand that it's a big decision," Sakai replied. "But ultimately he (Bloomberg) gets off scott free (sic) if people like you with important information don't step forward."

"I can't commit to anything. I won't commit to anything," the person told her.

By coming forward with her complaint, Sakai said she sacrificed her career at Bloomberg LP. Prior to her departure from the firm, she said she was "a top performer in New York sales, and I was making a good six figure salary," according to notes compiled as part of her complaint to the New York State Division of Human Rights.

In the transcribed notes from phone calls with friends and colleagues after Sakai claimed Bloomberg made the "kill it" remark, Sakai described her conflicted feelings about leaving the company.

"That's what really infuriates me. You knew how I worked … I was totally devoted to that company," Sakai told a senior manager at Bloomberg LP a year after the alleged "kill it" comment. "I enjoyed my job. I was good at it. I was getting great pay."

Sakai eventually settled her 1997 lawsuit against Bloomberg and his company out of court and moved West. She was paid an undisclosed amount of money and signed a nondisclosure agreement.

Last week, the Bloomberg campaign announced it would release three women it identified as having complaints tied directly to comments Bloomberg himself allegedly made from their nondisclosure agreements. A senior campaign official confirmed to ABC News that Sakai is one of the three women.

As of Monday, according to Bloomberg's campaign, Sakai had not reached out the company about dissolving her nondisclosure agreement.