How the justices weighed Trump's rhetoric on Muslims in travel ban decision

A question for the court was what role, if any, Trump's language should play.

As part of the Supreme Court's decision to uphold President Donald Trump's travel ban, the justices had to decide how to consider Trump's previous harsh rhetoric about Muslims and whether that could mean the ban unfairly blocked Muslims from entering the U.S. because they were traveling from countries with Muslim-majority populations.

Hawaii and the other plaintiffs argued that the proclamation was based on hostility to Muslims and their religion, citing some of Trump's statements about Muslims and Islam as a presidential candidate including calling the policy a "Muslim ban."

The court ultimately sided with the administration's argument that the travel ban was a national security issue based on countries with a flawed vetting process, not based on the religion of the population in those countries.

The 5-4 majority said they did not consider Trump's public statements enough evidence to make that connection because the proclamation did not specifically mention religion and it did not ban Muslims from all countries from entering the U.S.

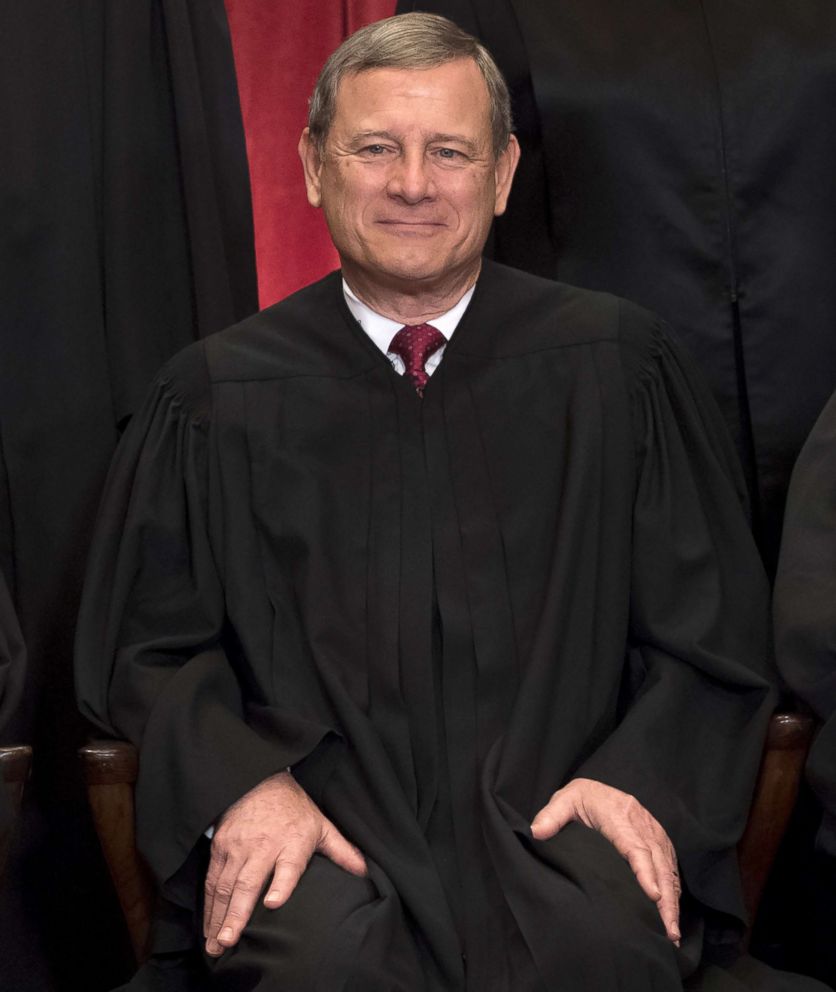

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the court's decision that the case had to look at the authority of the presidency to make an order like the travel ban, not Trump's specific statements.

"The issue, however, is not whether to denounce the President's statements, but the significance of those statements in reviewing a Presidential directive, neutral on its face, addressing a matter within the core of executive responsibility," Chief Justice John Roberts said in the decision. "In doing so, the Court must consider not only the statements of a particular President, but also the authority of the Presidency itself."

But the minority, especially Justice Sonia Sotomayor, said that after seeing Trump's comments a reasonable observer "would conclude that the primary purpose of the Proclamation is to disfavor Islam and its adherents by excluding them from the country."

Sotomayor described several of Trump's previous comments in her dissent and even a poem that he often read at campaign rallies called "The Snake," intended as a warning about Syrian refugees entering the U.S., and anti-Muslim videos retweeted from the president's account.

Sotomayor also pointed out that Trump has never "disavowed" any of his comments about Islam and that even though the majority did not consider his statements Trump and his advisors have acknowledged that all three travel bans addressed issues Trump previously discussed on the campaign.

"The President's statements, which the majority utterly fails to address in its legal analysis, strongly support the conclusion that the Proclamation was issued to express hostility toward Muslims and exclude them from the country," Sotomayor said. "Given the overwhelming record evidence of anti-Muslim animus, it simply cannot be said that the Proclamation has a legitimate basis."

Roberts specifically pushed back on the idea that the travel ban targeted Muslims because several of the specific countries included had a Muslim majority, saying the policy doesn't cover the entire Muslim population and that the countries were previously designated national security risks by Congress or other administrations.

"The text says nothing about religion. Plaintiffs and the dissent nonetheless emphasize that five of the seven nations currently included in the Proclamation have Muslim-majority populations. Yet that fact alone does not support an inference of religious hostility," Roberts said, adding that the policy doesn't cover the entire Muslim population and that the countries were previously designated national security risks by Congress or other administrations.

Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote a separate opinion joining with the majority. He said it is important to note that even if officials' comments are outside the Court's jurisdiction or can't be evaluated as part of a case, "that does not mean those officials are free to disregard the Constitution and the rights it proclaims and protects."

"From these safeguards, and from the guarantee of freedom of speech, it follows there is freedom of belief and expression," he said. "It is an urgent necessity that officials adhere to these constitutional guarantees and mandates in all their actions, even in the sphere of foreign affairs. An anxious world must know that our Government remains committed always to the liberties the Constitution seeks to preserve and protect, so that freedom extends outward, and lasts."

Justice Stephen Breyer said the president's statements were evidence of bias against Islam as a religion, saying in his dissent "I would, on balance, find the evidence of antireligious bias, including statements on a website taken down only after the President issued the two executive orders preceding the Proclamation... a sufficient basis to set the Proclamation aside."

Sotomayor's dissent also compared the travel ban decision to another case issued this year where the Court ruled in favor of a Colorado baker who declined to bake a wedding cake for a gay couple. In that case, the court ruled in favor of the baker in part because of comments made by members of the Colorado Civil Rights Commission that the Court said showed a negative bias toward religion.

Sotomayor argued the same principle from that case should have applied when the Court considered the travel ban.

"In both instances, the question is whether a government actor exhibited tolerance and neutrality in reaching a decision that affects individuals' fundamental religious freedom. But unlike in Masterpiece, where a state civil rights commission was found to have acted without "the neutrality that the Free Exercise Clause requires,"...the government actors in this case will not be held accountable for breaching the First Amendment's guarantee of religious neutrality and tolerance," she said.