6 questions about Trump's 2nd impeachment trial answered, much still unknown

Much has changed since Trump's first impeachment trial.

For the second time in 13 months and for the fourth time in American history, the Senate will again embark on yet another impeachment trial, the second for President Donald Trump.

But much has changed since the House first passed articles of impeachment against Trump: The president's term expires next week; there is a new administration coming in with new legislative priorities; and the COVID-19 pandemic continues to rage.

As a result, much remains unknown about how the trial will play out this time.

When will the trial begin?

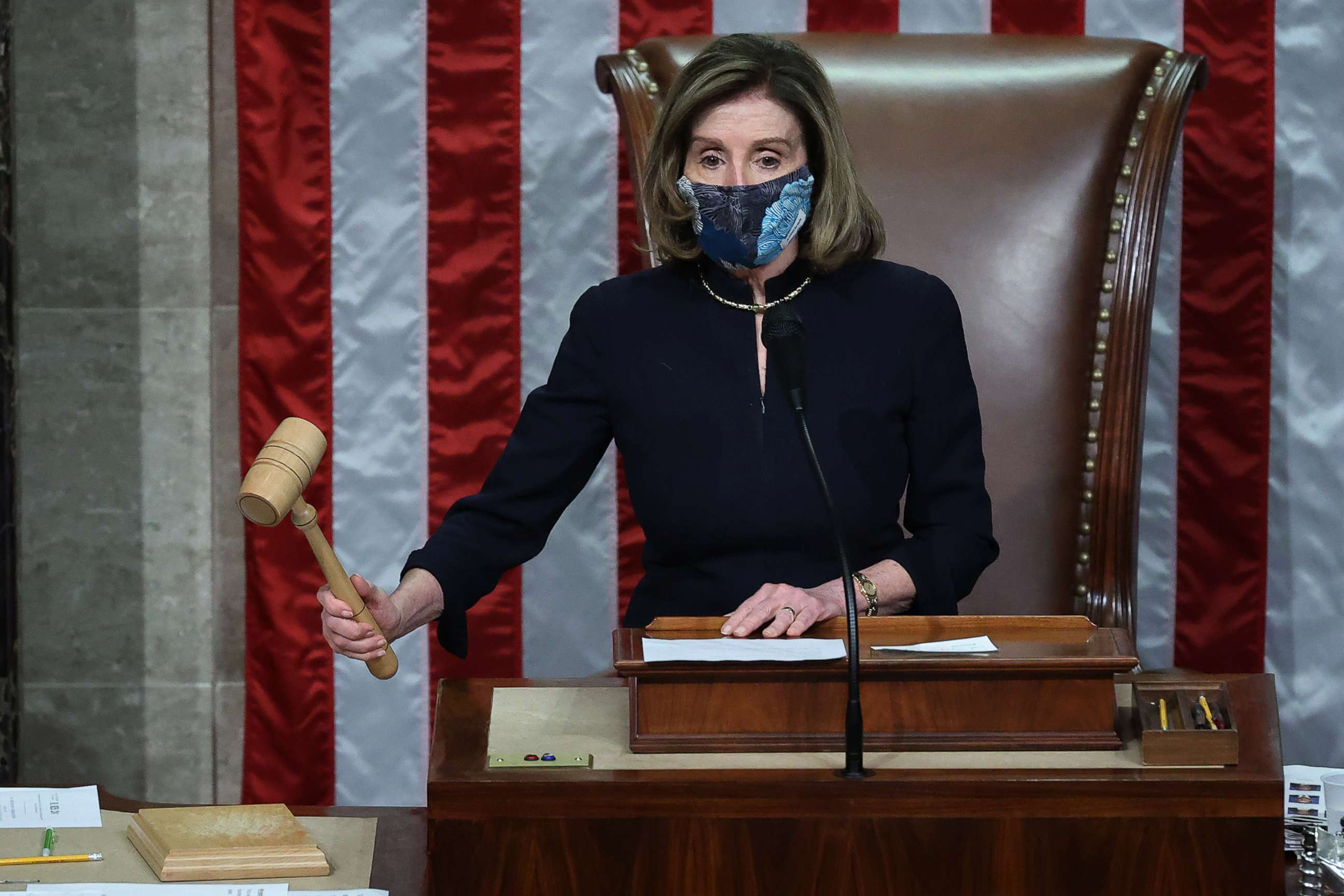

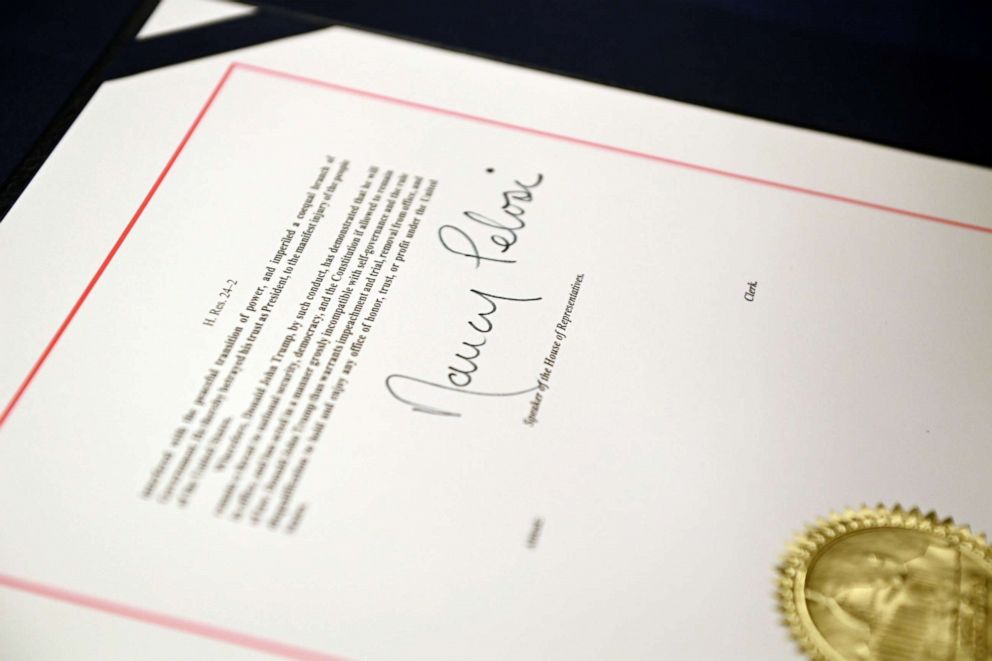

Now that the House has approved an article of impeachment accusing Trump of inciting violence against the U.S. government, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi essentially determines when the trial starts. Proceedings are triggered when Pelosi authorizes the House impeachment managers, who she formally appointed Wednesday, to formally deliver the article to the Senate chamber.

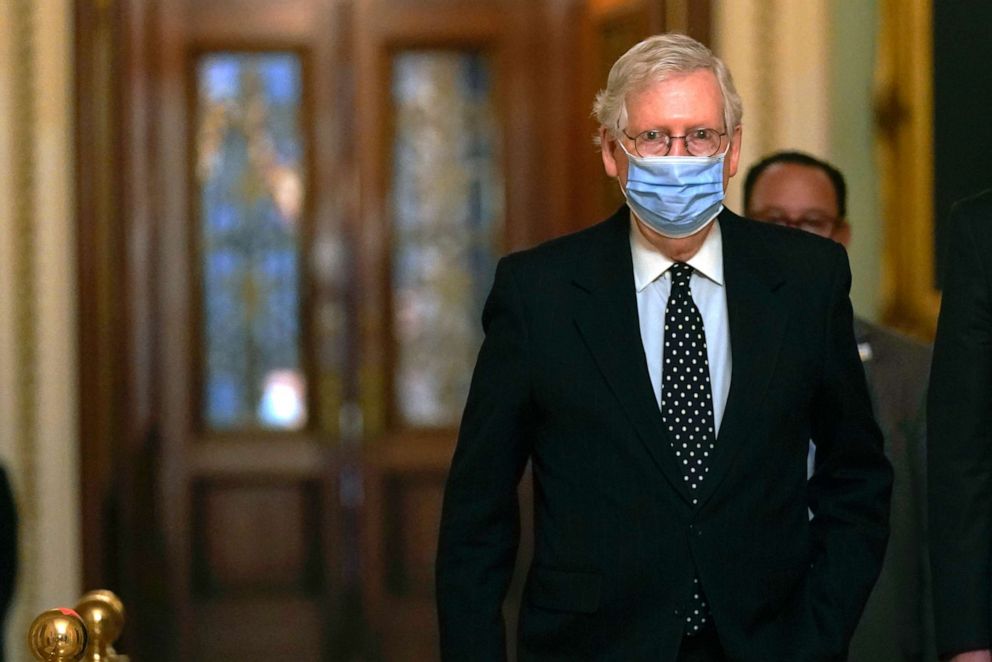

But the Senate needs to be in session to confirm receipt and they're not expected to reconvene until Jan. 19. Minority Leader Chuck Schumer has urged Majority Leader Mitch McConnell to reconvene the Senate for an emergency session so that the trial can begin hastily, but McConnell's office confirmed to ABC News Wednesday that McConnell told Schumer he had no intention of calling members back to town early.

That means the earliest any action could take place related to the trial would be Tuesday, Jan. 19. If Pelosi decides to send the article to the Senate chamber that day, the first day of the trial, which is largely ceremonial and will include exhibition of the article and the swearing in of the chief justice to preside and the senators as jurors, would occur on Jan. 20, Inauguration Day.

Pelosi has remained mum on her plans, but in a statement Wednesday evening, McConnell appeared to be urging the speaker to hold off on transmitting the article until President-elect Joe Biden is sworn in.

"Even if the Senate process were to begin this week and move promptly, no final verdict would be reached until after President Trump had left office. This is not a decision I am making; it is a fact. The President-elect himself stated last week that his inauguration on January 20 is the 'quickest' path for any change in the occupant of the presidency," McConnell said. "In light of this reality, I believe it will best serve our nation if Congress and the executive branch spend the next seven days completely focused on facilitating a safe inauguration and an orderly transfer of power to the incoming Biden Administration."

Given that a trial is all but certain to take place after Trump leaves White House, there are new questions about the constitutionality of it taking place at all.

Will Trump mount a defense?

With the trial starting as soon as next week, the president has yet to organize a defense team and many of the lawyers involved last time do not plan to return for round two.

During the impeachment trial last winter, Trump's legal team and the House managers were each allotted up to 24 hours to present their arguments. Trump's team used about half of that time to mount their defense. Senate Republicans blocked witnesses from being called for the trial, so Trump's legal team did not depose them.

But the president currently lacks a comprehensive legal strategy, according to sources close to him who said his top lawyers have refused to represent him.

Trump has asked his top aides how a Senate trial could look this time around and even raised the idea of testifying himself, which his advisers dissuaded him from pursuing.

At this point, however, it remains unclear whether the core defense of the Trump team would focus on the events of Jan. 6 or whether his lawyers would attempt to challenge whether a trial can even occur once Trump becomes a former president.

Is it even constitutional to hold this trial?

Trump's second impeachment trial will be the first to occur after the president facing impeachment has left office and some lawmakers and constitutional scholars question whether putting a former president on trial is constitutional.

In a statement released late Wednesday evening, Sen. Tom Cotton, R-Ark., argued that the Senate doesn't have the authority to hold a trial once Trump has left office.

"The Founders designed the impeachment process as a way to remove officeholders from public office -- not an inquest against private citizens," Cotton said in a statement. "The Constitution presupposes an office from which an impeached office holder can be removed.

Cotton's opinion is shared by some other lawmakers, former judges and scholars.

Michael Luttig, a former federal appeals court judge, argued similarly in a Washington Post op-ed, said that "The very concept of constitutional impeachment presupposes the impeachment, conviction and removal of a president who is, at the time of his impeachment, an incumbent in the office from which he is removed."

Philip Bobbitt, a constitutional law scholar at Columbia Law who has written a book on impeachment, told ABC News that he agrees with Cotton and Luttig's analysis.

"I think that people are so enraged by the prospect of Trump getting away with this that their justifiable outrage carries away their legal judgment," Bobbitt said.

But not all scholars are in agreement. Some have argued that Congress has full authority to pursue impeachment for actions taken at the back end of a president's term, in an effort to disqualify a president from holding future office.

Lawrence Tribe, a Harvard law professor and constitutional scholar who has written about impeachment, wrote in a Washington Post op-ed that an officer no longer serving in their post has "no bearing" on whether that person can be "barred permanently from office upon being convicted."

"Concluding otherwise would all but erase the disqualification power from the Constitution's text: If an impeachable officer became immune from trial and conviction upon leaving office, any official seeing conviction as imminent could easily remove the prospect of disqualification simply by resigning moments before the Senate's anticipated verdict."

There are a few historical examples of officials being impeached post-departure from office, including a judge, a former senator and a secretary, but a president has never faced a post-presidency impeachment.

ABC News Legal Analyst Kate Shaw said Wednesday on "Good Morning America" that arguing that post-departure impeachments are never permissible could be "constitutionally deeply problematic."

"To hold that post-departure impeachment proceedings are never permissible would essentially insulate conduct committed in the last stretch of a presidency," Shaw told ABC News Chief Anchor George Stephanopoulos. "It would basically say a president can’t be held accountable for the things that he does in the final weeks or months in office."

While Republican leadership hasn't publicly stated any plans to mount challenges surrounding the constitutionality, Sen. Pat Toomey, who earlier this month said he believes Trump has committed impeachable offenses, called the Senate's authority to hold a trial "debatable." Toomey did, however, commit to serving as an impartial juror if such a trial were to commence.

A big open question remains just how many Republican senators will vote to convict Trump and many of them have issued statements stating their intention to listen to arguments as impartial jurors in a trial.

McConnell, who in a statement Wednesday did rule out voting to convict Trump at the conclusion of a trial, said that the "Senate process will now begin at our first regular meeting following receipt of the article."

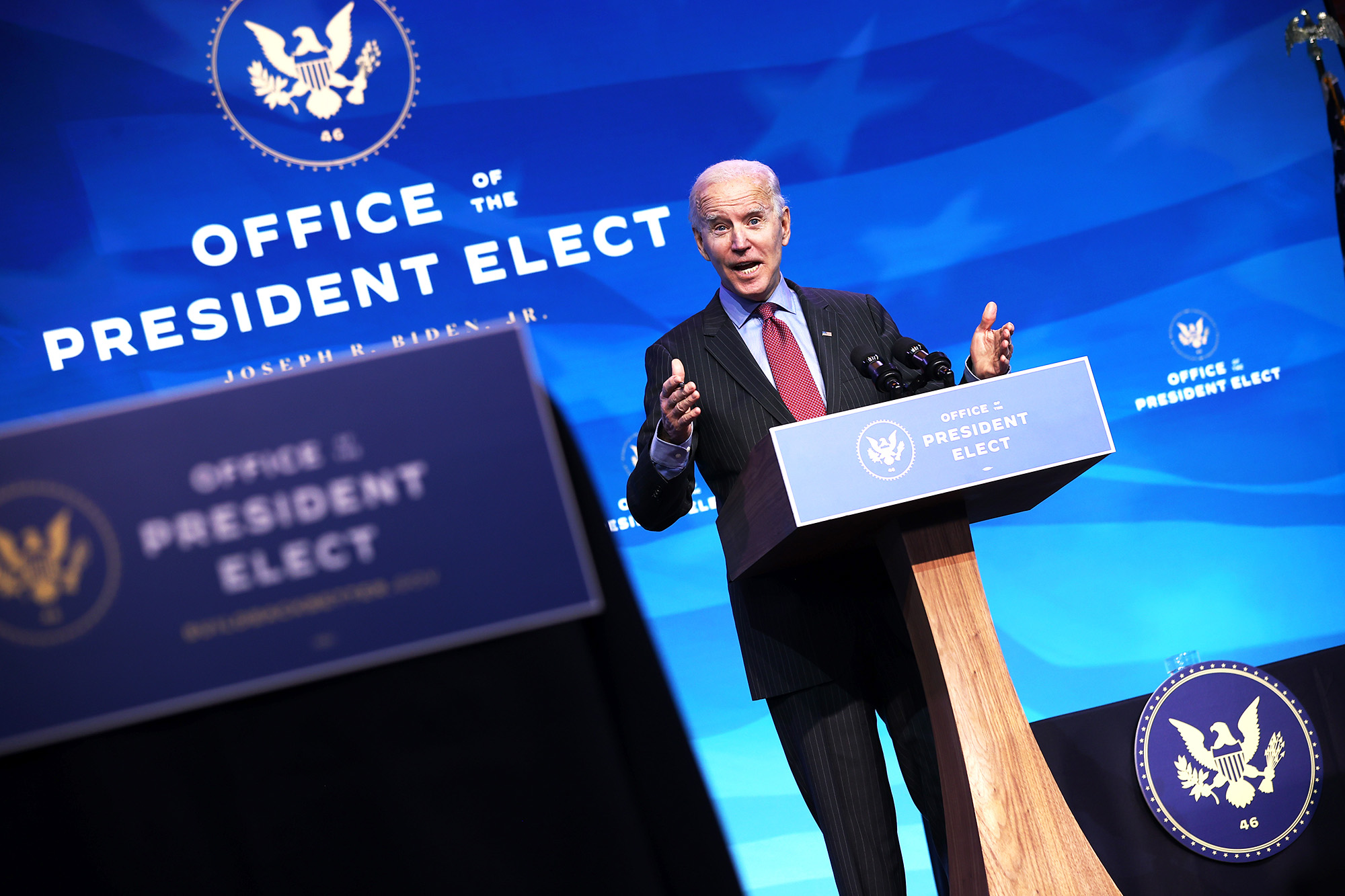

Will Biden be able to accomplish his agenda while the trial goes on?

Assuming the trial commences, if the Senate hopes to accomplish any business unrelated to it in the earliest days of the Biden administration, Democrats and Republicans will need to reach an agreement to allow business to proceed during hours that the trial is not being conducted.

This so called "dual-track" approach requires consensus, and Biden has already spoken to McConnell about establishing a path forward that would allow the Senate to conduct outside business when the trial is not ongoing.

At least one Senate Democrat, Joe Manchin of West Virginia, expressed concern before the House passed an article of impeachment that a Senate trial in the earliest days of the Biden administration might hinder the legislative body from getting to work on key pieces of the new president's agenda.

In the earliest days of the administration, the Senate would normally be busy holding confirmations for and voting on key administration positions. Biden and Democrats have said they hope to expeditiously pass additional COVID-19 relief legislation, another measure that will require time.

Biden said Tuesday he had spoken with lawmakers about whether it was possible to "go half-day on dealing with the impeachment, and half a day getting my people nominated and confirmed in the Senate, as well as moving on the package?"

"That's my hope and expectation," he said.

How will COVID-19 affect the proceedings?

Under the standing set of rules for impeachment, all Senators are required to be in their seats at all times during the trial, listening to the arguments of the impeachment managers and the defense team while being presided over by the chief justice. The Senate sergeant at arms is permitted to "compel" their appearance.

But this rule does not take into account a pandemic, and, as with virtually everything in the Senate, these rules can be bent if there's agreement.

According to Bobbitt, Senate leadership could make any sort of changes it wishes, including changes to social distancing or attendance requirements, if they can get members to agree to these changes when the trial rules are adopted.

"They do have the ability to change the rule but the model for the Senate is not its ordinary proceedings," Bobbitt said. "The model is an actual criminal trial. Jurors can be compelled to stay in the jury room."

Also not clear is whether members would be required to wear masks. The House has gone so far as to implement fines for members who do not wear masks on the House floor, but in the Senate, there's no rule requiring masks to be worn. Almost all members wear masks, but some remove them when they're speaking.

It is unclear if there would be any sort of rule requiring members and their staff to mask up for all those hours. All lawmakers have had the opportunity to receive the COVID-19 vaccination. But not all staff have.

The Office of the Attending Physician has previously encouraged social distancing in hearing rooms and on the Senate floor, but did not reply to a request for comment on whether they've issued specific guidance on an impeachment trial.

Will there be enough Republican support to convict Trump?

The article of impeachment passed out of the House with the support of 10 Republican members of the House, making it far less partisan than the last Trump impeachment effort. But conviction on the Senate side requires the vote of two-thirds of the body, which means that even if all Democrats vote to convict Trump, 17 Republicans will need to join them.

At this moment, no single Republican has firmly committed to voting to convict, though several have signaled willingness to.

Sen. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, said in a statement Thursday that the House acted "appropriately" by impeaching the president. Sen. Ben Sasse, R-Neb., has also signaled willingness to consider the article, as have others.

McConnell, in a letter to his colleagues Wednesday, signaled he has not ruled out voting to convict Trump.

"I intend to listen to the legal arguments when they are presented to the Senate," McConnell said.

McConnell's vote may have the power to sway others who are on the fence. ABC News is tracking at least eight GOP senators who have declined to comment on their position, or given statements that don't indicate how they will vote.

Still, not all those who were critical of Trump's actions before the attack on the Capitol will necessarily vote against him.

Sen. Rob Portman, R-Ohio, did not say how he would vote in a statement Wednesday, but said he'll take into account "what is best to help heal our country rather than deepen our divisions."