Reflecting on Massachusetts' historic gay rights ruling, 15 years later: ANALYSIS

A journalist reflects on how much things have changed in 15 years.

The moment felt historic. But it also felt precarious, as if the history being made could be unmade at any moment.

The Boston Globe had assigned me, then a junior political reporter, to man the steps of City Hall in Cambridge, Mass., as the clock struck midnight and the calendar flipped to May 17, 2004.

Same-sex marriage became legal at that moment, in accordance with a then-controversial Supreme Judicial Court ruling that no one was quite sure would stand.

A first crush of 41 couples lined up in the middle of the night to be the first gays and lesbians to be legally married in the United States, with some of the plaintiffs in the court case getting front-of-the-line treatment.

The scene was jubilant. A small group of protesters was drowned out by an exuberant crowd of gay activists and curious locals who had gathered under the brightly lit ancient bell tower in Central Square to witness history.

With 15 years’ remove from that moment, it’s difficult to remember how uncertain it all felt.

Just a few months earlier, San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom had ordered that marriage licenses be issued to gay couples – only to have the California Supreme Court later invalidate them and the marriages that had been performed.

From the White House, President George W. Bush called the Massachusetts court ruling “deeply troubling” and voiced support for a constitutional amendment to ban gay marriage nationwide.

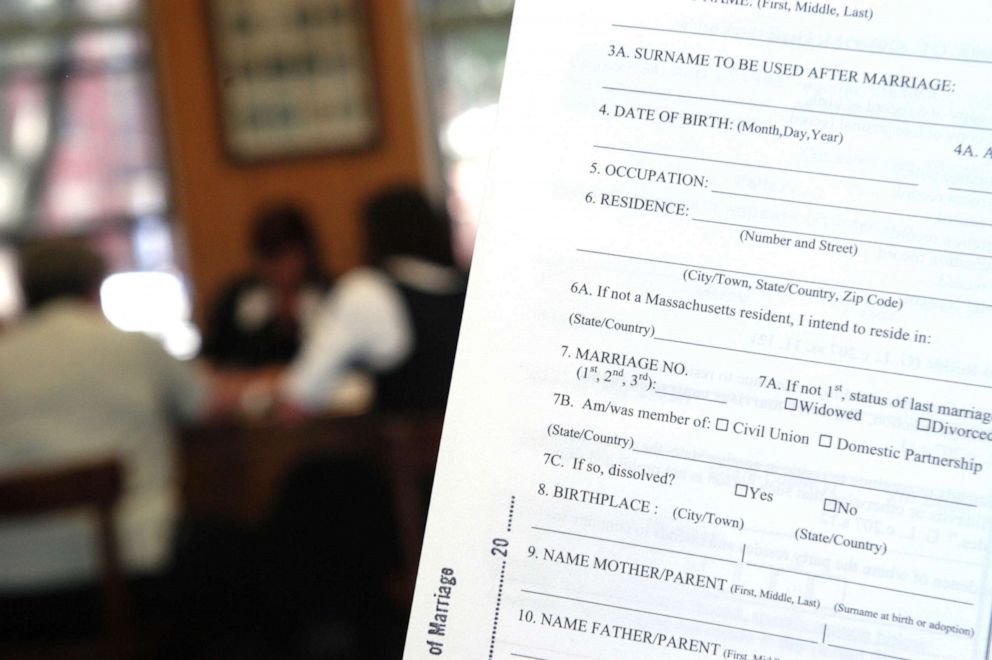

Inside Massachusetts, Republican Gov. Mitt Romney was forced to implement a court ruling with which he vehemently disagreed, and that threatened to disrupt his future presidential prospects. Romney would not make it easy for gay couples; among other bureaucratic obstacles, he invoked a 90-year-old state law that had been written to block interracial marriage to prevent same-sex couples from other states from coming to the Bay State to wed.

It wasn’t just Republicans who were uncomfortable with how fast things were moving. Allowing gay couples to marry wasn’t a mainstream position in either political party back in 2004.

Sen. John Kerry – then a senator from Massachusetts, and the Democratic presidential nominee in 2004 – opposed gay marriage throughout his campaign, favoring civil unions instead, in what was viewed as a progressive position at the time.

A full presidential cycle later, candidate Barack Obama and his running mate, Joe Biden, opposed nationwide gay marriage in favor of civil unions.

“I believe marriage is between a man and a woman. I am not in favor of gay marriage,” Obama said in November 2008 – on the eve of his election.

It would take another four years -- and fully eight years after wedding bells first chimed for same-sex couples in Massachusetts -- before Biden pronounced himself comfortable with gay marriage. Obama – then running for reelection – followed suit, acknowledging an “evolution” on the issue in an interview with ABC News’ Robin Roberts that made him the first president to support gay marriage.

Even at that time, in 2012, gay marriage was legal in only six states plus the District of Columbia. The landmark Supreme Court case establishing a fundamental right to marry came in 2015 – effectively ending a political debate made more urgent on those courthouse steps 11 years earlier.

Now, in 2019, an openly gay presidential candidate has been featured on the cover of Time magazine alongside his husband. The Republican president he might run against said, just this week, he thinks “it’s great” that a married gay man is running.

In a pure historical coincidence, in May 2004 Pete Buttigieg was an undergrad at Harvard – in the very city, Cambridge, where the midnight marriage licenses were issued. The next time I interview him, I plan to ask him where he was that night.

I remember clearly the faces of many of those who got married and were celebrating those marriages in the middle of night, as TV lights illuminated rainbow flags.

Two faces in particular stand out to me.

They were those of an older interracial couple, probably in their 70s. I recall a bearded black man and a taller white man holding hands as they worked through the crowd and into the courthouse, smiling.

I thought at the time about the history they witnessed, and how improbable they must have found it that they would be able to marry. I wish I could ask them now if they find it even more remarkable that the politics around gay marriage have moved as quickly as they have since that day.