'A deliberate cover-up'?: US Figure Skating reckoning with sexual abuse allegations against Olympic coach

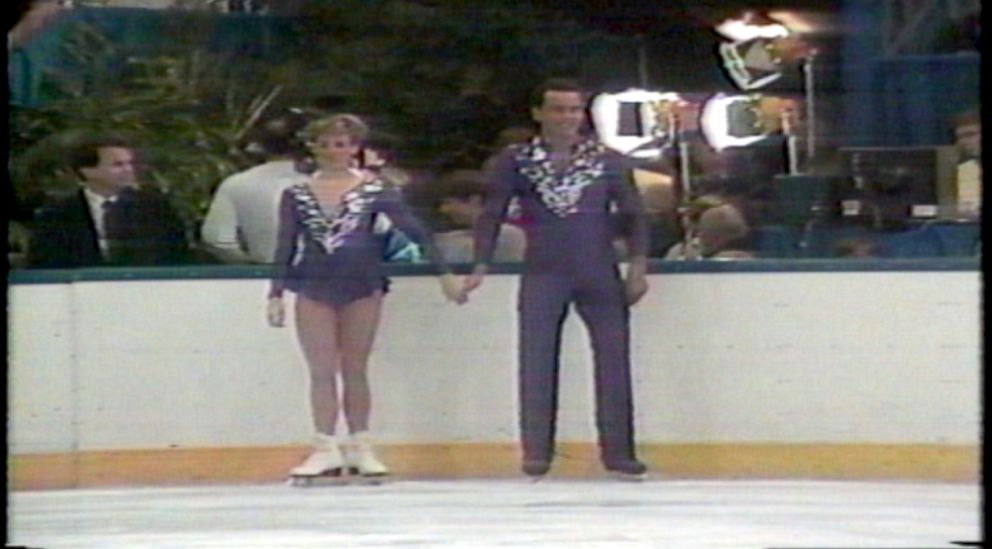

Craig Maurizi first accused Richard Callaghan in 1999 of sexually abusing him.

Craig Maurizi has been here before.

In 1999, he accused Richard Callaghan, once figure skating’s top coach, of sexually abusing him when he was one of his students more than a decade earlier. He reported the abuse to the sport’s national governing body. He told his story to several major media outlets.

But Callaghan issued strong denials. Maurizi’s claims were dismissed. Callaghan kept coaching.

Now, nearly two decades later, Maurizi has brought his allegations against Callaghan – and U.S. Figure Skating’s handling of those allegations – back into the spotlight. He filed a new complaint to the U.S. Center for SafeSport, the U.S. Olympic Committee’s misconduct watchdog, in January.

An exclusive interview with Maurizi will air Tuesday morning on Good Morning America.

This time might be different. Last week, the U.S. Center for SafeSport suspended Callaghan, pending a new investigation of those earlier allegations. His name was added to U.S. Figure Skating’s roster of banned or suspended members late Wednesday night — listed alongside more than a dozen others publicly shamed for various alleged misdeeds — barring him from all USFS-sanctioned events until further notice.

Upon hearing the news of Callaghan’s suspension, Maurizi says he was overcome by a mix of emotions. Happiness. Vindication. Relief. Then he settled on another one.

“The truth is that as the days are passing,” Maurizi told ABC News, “my anger is growing.”

That’s because Callaghan had been permitted to continue coaching under the auspices of U.S. Figure Skating despite the organization receiving from Maurizi what he calls “a mountain of evidence” to support his claims.

Maurizi submitted a tranche of documents to SafeSport – mostly letters to and from skaters, coaches and skating officials regarding his case – many of which had also been submitted to U.S. Figure Skating nearly 20 years ago. He also provided those same documents to ABC News.

“The more I thought about it the more it became clear that I had an obligation to try again to stop this man from coaching once and for all,” Maurizi told ABC News. “I would have a tremendous sense of guilt if I found out that he was still doing this to children and I didn’t do anything, so I had to do everything in my power to stop it.”

Maurizi is also exploring his legal options. He recently retained the services of the California law firm that represents many of the athletes who accused USA Gymnastics team doctor Larry Nassar of sexual abuse. He says he is focused on “getting the job done,” making sure Callaghan never coaches again.

When reached for comment on Friday, Callaghan told ABC News he had not been notified of his suspension. When asked by ABC News about Maurizi’s allegations, however, Callaghan said he had no further comment.

“That’s 19 or 20 years ago,” Callaghan said. “I have nothing to say.”

The documents, however, indicate that U.S. Figure Skating took no disciplinary action following detailed allegations of sexual misconduct levied against Callaghan by several male skaters stemming from incidents from 1977 to 1995.

U.S. Figure Skating has said that Maurizi’s claims were dismissed without full consideration because skating bylaws stipulated that alleged violations be reported within 60 days, and according to a spokesperson, U.S. Figure Skating had not received any abuse claims about Callaghan before or since.“Prior to Mr. Maurizi’s complaint regarding the alleged sex abuse by Mr. Callaghan, there was never a complaint submitted to U.S. Figure Skating prior to 1999 nor has any complaint been received from anyone since regarding any alleged misconduct by Mr. Callaghan,” said a spokesperson in a statement.

Both Maurizi and the former skating official who initially received Maurizi’s grievance are highly critical of the association’s handling of his allegations, however.

“It was, without a doubt,” Maurizi told ABC News,” a deliberate cover-up.”

‘FIGURE SKATING IS NO EXCEPTION’

U.S. Figure Skating is the latest national sports governing body to reckon with its alleged failure to protect young athletes. USOC CEO Scott Blackmun resigned in February amid ongoing scandals surrounding the handling of sexual abuse allegations by USA Gymnastics and USA Swimming.

According to Christine Brennan, a sports columnist and ABC News contributor who trailed several top skaters and coaches, including Callaghan, during the 1994-95 season for her 1996 book Inside Edge: A Revealing Journey into the Secret World of Figure Skating, the culture within figure skating is such that coaches are given an incredible amount of responsibility, and control, over their students.

"Figure skating is a sport in which parents often give their kids over to the coaches,” Brennan said. “The level of trust is extraordinary, even more than we see with gymnastics and swimming. Sometimes families split so the mother can move with the child who skates to follow a coach or go to a particular rink in another part of the country, while the father stays home with the non-skating kids. There is an inordinate amount of trust that a skating family places in a coach in a sport like figure skating."

This is the second such case to be brought to U.S. Figure Skating’s doorstep in recent weeks. Manly, Stewart & Finaldi, the California firm representing Maurizi, recently filed a lawsuit on behalf of a former member of the USA National Figure Skating Team against U.S. Figure Skating, former coach Donald Vincent and a pair of Los Angeles-area ice rinks. According to Vince Finaldi, cases like Vincent’s are “one more example of the culture of child abuse that is rampant in our Olympic sports programs.”

“Figure skating,” he said, “is no exception.”

Vincent was convicted in 2014 of abusing two of his students between 2007 and 2011 and is currently serving a sentence of 98 years to life in prison. According to the complaint, skating officials had received previous abuse allegations against him, raising the question of why he had been permitted to continue coaching.

“We believe that this is a problem with USA Figure Skating that has not been uncovered,” Finaldi told ABC News. “I think this is the beginning of an eye-opening inquiry."

A spokesperson for U.S. Figure Skating pushed back against that assertion, touting the organization’s policy of zero tolerance for abuse and harassment, pointing to a mandatory reporting rule put in place in 2000 and providing a timeline the organization says “makes clear that U.S. Figure Skating does not have ‘a systemic abuse problem.’”

When asked directly about the the two individual cases – one old, the other new – U.S. Figure Skating released a pair of statements that shed little light on how the allegations were handled.

“U.S. Figure Skating suspended the membership of Richard Callaghan on March 6, 2018, in compliance with the policies and procedures of the U.S. Center for SafeSport,” the statement reads. “This action prohibits Callaghan from participating, in any capacity, in any activity or competition authorized by, organized by, or under the auspices of U.S. Figure Skating, the U.S. Olympic Committee and all USOC-member National Governing Bodies, including U.S. Figure Skating-member clubs and/or organizations. As the U.S. Center for SafeSport has exclusive jurisdiction and adjudication of this matter, U.S. Figure Skating will have no further comment.”

The governing body was similarly tight-lipped on the subject of Vincent.

“U.S. Figure Skating has no comment on pending litigation other than to state U.S. Figure Skating denies all claims asserted against U.S. Figure Skating in the suit, and denies it has any liability in that matter.”

‘I LOOKED BACK … AND I WAS HORRIFIED’

Maurizi began taking lessons from Callaghan at the Buffalo Skating Club in 1976. He says Callaghan began abusing him the following year, when he was 14, showing him pornography, masturbating in front of him and grabbing him by the genitals. The alleged sexual encounters grew more intense, he says, after Maurizi followed Callaghan to the Philadelphia Skating Club in 1981, when Maurizi was 18, and ultimately included multiple instances of oral and anal sex, sometimes in group situations with other students.

In 1986, when he was 23, Maurizi says he began refusing Callaghan’s sexual advances. A pairs skater who once finished fifth at the U.S. National Championships, Maurizi quit skating competitively and turned to coaching, twice working as an assistant to Callaghan, once in San Diego and then again in Detroit, where they trained Tara Lipinski ahead of her gold-medal performance at the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano.

Lipinski’s decision following the competition to leave Callaghan’s stable of skaters to train exclusively with Maurizi led to a bitter feud between the two men, ending their professional relationship.

It was only then, Maurizi says, having finally distanced himself from Callaghan, that Maurizi realized the impropriety of his former coach’s behavior.

“I finally started thinking for myself,” Maurizi would say later. “And I looked back on some of the things that had happened to me, and I was horrified.”

After discussions with friends and, later, his then-wife, he decided to come forward. He says he reported the alleged abuse in a phone call with U.S. Figure Skating president Jimmy Disbrow, who ran the sport from 1998 to 2000, but fearing Callaghan’s reputation would deter a proper investigation, Maurizi also took his story to the media, eager to see Callaghan banned from coaching as soon as possible.

The New York Times published Maurizi’s allegations of “inappropriate sexual conduct” on April 11, 1999, alongside Callaghan’s vigorous denials, including suggestions that Maurizi’s claims were nothing more than character assassination motivated by a desire to poach more skaters from a now rival coach. Callaghan told the New York Times he never had sex with Maurizi and dismissed any suggestion that he had engaged in any improper behavior.

But Maurizi wasn’t alone in making allegations against Callaghan. One former student told the Times Callaghan exposed himself to him in 1992. Another said Callaghan made “inappropriate sexual remarks” to him in 1994. One former colleague of Callaghan’s told the Times three skaters told her in 1986 they had either seen or been subject to his sexual advances. Another said two skaters told her they saw him kissing a student in 1991.

In an appearance on ABC News’ Good Morning America the day after the New York Times first published the allegations, Maurizi told Diane Sawyer that he was aware of multiple other skaters who suffered similar abuses.

“I’ve spoken with five former male students who had inappropriate sexual relations with Richard,” Maurizi said.

‘BLATANT ATTEMPT TO INTERFERE’

Many of the same people who spoke to the Times ultimately submitted letters to U.S. Figure Skating supporting Maurizi’s allegations. And another former student submitted a letter saying when he was 21 he was twice “coerced” into sexual acts by Callaghan alongside Maurizi in 1983.

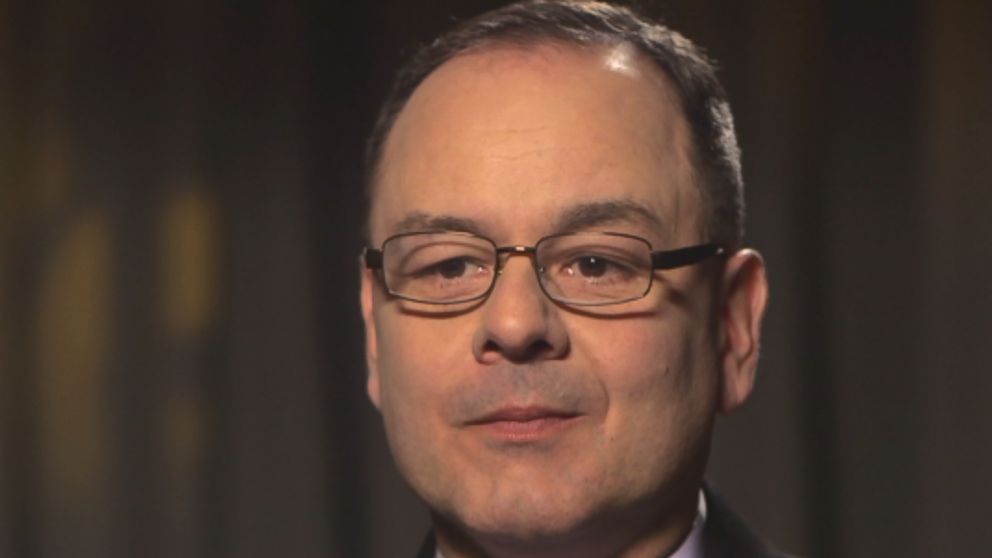

According to Steven Hazen, however, the former skating official who was charged with handling Maurizi’s initial complaint against Callaghan, an investigation never took place.

In an April 23, 1999, letter, Thomas James, an attorney representing U.S. Figure Skating, told Hazen that he had been “disqualified” from handling the case. James argued recent postings by Hazen on an Internet forum urging users to refrain from speculating about the case called into question "your ability to fairly and impartially address this matter” and could even be construed as "threats of potential action" that "likely constitute an inappropriate exercise of power and authority.”

He instructed Hazen to forward any materials to him and take no further action regarding the case.

Hazen was outraged. In response to James, Hazen “unequivocally and completely rejected” James’ assertions, blasting the letter as a “blatant attempt to interfere with the grievance process” in an “effort to intimidate me into abandoning my responsibilities.”

“It wasn’t clear to me where the resistance lay,” Hazen told ABC News, “but it was clear to me that there were people at USFSA who did not want that matter to go forward.”

On May 4, USFS president Disbrow notified Maurizi that Hazen had been removed from handling the case. “Please be advised that, on this particular grievance matter, Mr. Hazen will not serve in the position of Grievance Committee Chair and does not have the authority to communicate with you in the capacity,” Disbrow wrote.

Hazen forwarded materials he had collected to the ethics committee chair. Under the procedures then in place, Hazen told ABC News, if that official decided the claims had merit, he would refer the matter back to the grievance committee, and a three-person commission would be empaneled to investigate the claims, interview witnesses and make a determination.

That never happened. Just two weeks later, Hazen was not reappointed as grievance committee chair after serving in his position for only one year, and the head of the ethics committee now handling the claim was also being replaced.

Ultimately, it was Disbrow, a few weeks later, who made the final determination. He wrote to the new ethics committee chair Jon Jackson on May 27, ruling that Maurizi's claims were being dismissed "for a variety of reasons, both legal and equitable, pertaining principally to delay and limitation of actions.” A copy of that letter can be read below.

Translation: They were too old. Disbrow instructed Jackson to deliver the news to Maurizi. “I have determined that … your grievance is time barred,” Jackson wrote to Maurizi the following day, noting the governing body’s bylaws stipulate that grievances must be filed within 60 days of the alleged violation or its discovery.

(The U.S. Center for SafeSport, which now has exclusive jurisdiction over allegations of sexual misconduct reported to national sports governing bodies, does not time bar any claims.)

The final ruling raises several questions for Hazen. “It does raise a red flag that actions were taken that did not conform to procedure,” Hazen told ABC News. “I believed that the USFSA had the full discretion to move forward if they wanted to.”

Maurizi told ABC News that he was never interviewed about his allegations by Jackson, Disbrow (who died in 2002), or anyone else at U.S. Figure Skating.

Jackson issued a statement that did not seem to address his handling of the case, instead referring to his past intention to write a tell-all book unrelated to the Maurizi case. “Many years ago, US Figure Skating learned that I was writing a tell-all book for reasons unrelated to the topic,” Jackson told ABC News in an email. “Immediately, USFS threatened to sue me for a number of reasons … USFS did not sue me. This was not only because everything in my book was truthful and could be proven, but also because I did not breach any confidences I held having served as Ethics chair. Having avoided the legal wrath of US Figure Skating, I’m not about to violate those confidences now.”

For his part, Disbrow told the Times back in 1999 that the claim’s merits were not judged. ''The whole process is that you try to do things that are timely,'' Disbrow told the Times. ''It's not an issue of guilt on anybody's part. I'm not saying 'right or wrong' on anybody's part. The fact is, this thing is 14 years old.''

James, who still acts as legal counsel to U.S. Figure Skating, referred a request for comment to the association’s spokesperson, who released a statement refuting Hazen’s accussations.

“The characterization that U.S. Figure Skating or its outside counsel attempted to subvert the grievance process or intimidate Mr. Hazen is simply not true,” the statement reads. “Mr. Hazen was excused from serving as Grievance Committee Chair on this specific matter because of internet communications he made regarding the case before the grievance had even been filed. Mr. Hazen was requested to take no action in regard to the grievance. U.S. Figure Skating believes that the grievance was handled properly according to the organization’s rules.”

A U.S. Figure Skating spokesperson told ABC News she couldn’t speak to the thoroughness of the association’s review of Maurizi’s claims.

“It was so long ago,” she said.

‘YOU HAVE TO WONDER’

An additional complaint filed by Maurizi with the Professional Skaters Association, which trains and credentials coaches, didn’t fare much better. In October of 1999, CBS News reported that the three-person committee examining Maurizi’s claims “unanimously found no violation of the ethics standards of the organization.”

PSA executive director Jimmie Santee defended his organization’s handling of the claims but told ABC News he would be reviewing their policies.

“What we would look at now is totally different from where we were at 20 years ago,” Santee said. “We are going to always review our policies and make sure we’re doing our best every time. We care about what happens to these kids.”

Both Maurizi and Callaghan continued coaching. Maurizi, now 55, still trains top skaters. He recently returned from the 2018 Winter Olympics in South Korea, where he coached an Olympic qualifier from Switzerland. Callaghan, meanwhile, now 72, appears to have faded from the limelight. He told ABC News he has retired to Florida but still coaches a few times per week.

Until Friday, Callaghan had been publicly listed as the chief operating officer of Champions of America, a skating clinic owned by his former student Todd Eldredge, a three-time Olympian and former world champion.

Callaghan would not confirm his employment, but the company’s website had advertised private skating lessons — $57 for one half hour — with Callaghan alongside his phone number and email address. A brochure for Todd Eldredge’s Champions of America even sold lessons on the promise of Callaghan’s glory days.

His credentials are impressive: “World & Olympic Champion Coach; PSA Coach of the Year; Level 10 Ranking Coach,” the brochure read. “A Level 10 Ranking is the highest ranking given by the PSA for elite coaches who have multiple World or Olympic Champions in any figure skating discipline.”

A list of former students, all national or world champions, included some of the sport’s biggest stars: Todd Eldridge, Tara Lipinski, Nicole Bobek.

Eldredge declined to comment on Callaghan’s suspension but told ABC News that Callaghan was no longer an employee of the company. On Friday afternoon, after ABC News broke the news of Callaghan’s suspension, pages bearing his name and photograph appeared to have been taken down. (Tara Lipinski did not immediately respond to a message seeking comment.)

Next steps are uncertain. A spokesperson for the U.S. Center for SafeSport told ABC News the organization does not comment on active matters, but said in cases involving abuse of minors, the organization always reports the matter to law enforcement.

Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, a Democrat from New Hampshire who has been pushing for the creation of a committee to investigate the USOC, said this case offers more evidence of the need for increased oversight.

“Glad to see some form of accountability in response to these heinous allegations, but it’s unconscionable that it took 2 decades,” she tweeted. “Why did it take so long? This is why we need a special committee to investigate USOC.”

But as sports columnist Christine Brennan notes, the damage might have already been done.

“It’s good to see USFS act now after SafeSport’s suspension of Callaghan,” she said. “But you have to wonder: how many dozens of boys and young men did Callaghan interact with over the past two decades? That’s incredibly troubling."

If you have information about this case or a similar case, please contact Pete Madden (pete.a.madden@abc.com) or Cho Park (cho.park@abc.com).

ABC News’ Shah Rahmanzadeh, Maureen Sheeran and Noor Ibrahim contributed to this report.