Why the Second Amendment may be losing relevance in gun debate

Experts said legislatures are doing the work in setting the landscape on guns.

This report is a part of "Rethinking Gun Violence," an ABC News series examining the level of gun violence in the U.S. -- and what can be done about it.

In the bitter debate over gun control, battle lines are often drawn around the Second Amendment, with many in favor of gun rights pointing to it as the source of their constitutional authority to bear arms, and some in favor of tighter gun control disagreeing with that interpretation.

But if the purpose of the debate is to reduce the tragic human toll of gun violence, the focus on Second Amendment is often misplaced, according to many experts on guns and the Constitution.

They say the battle lines that actually matter have been drawn around state legislatures, which are setting the country's landscape on guns through state laws -- or sometimes, the lack thereof.

Joseph Blocher, professor of law and co-director of the Center for Firearms Law at Duke Law School, described the patchwork of state laws that exists across the country as a "buffer zone" for the Second Amendment.

"Before you even get to the Constitution, there's a huge array of other laws super protecting the right to keep and bear arms," Blocher said. "This collection of laws is giving individuals lots of protection for gun-related activity that the Second Amendment would not necessarily require, and certainly, and in almost all of these instances, that no lower court has said the Second Amendment would require."

Watch ABC News Live on Mondays at 3 p.m. to hear more about gun violence from experts during roundtable discussions. And check back tomorrow to read about background checks and how effective they are.

Adam Winkler, a professor of law at the UCLA School of Law, also said the Second Amendment is losing its legal relevance in distinguishing lawful policies from unlawful ones as the gap between what he calls the "judicial Second Amendment" and the "aspirational Second Amendment" widens.

Winkler defines the "judicial Second Amendment" as how courts interpret the constitutional provision in their decisions, and the "aspirational Second Amendment" as how the amendment is used in political dialogue. The latter is "far more hostile to gun laws than the judicial one," he said -- and also more prevalent.

Before you even get to the Constitution, there's a huge array of other laws super protecting the right to keep and bear arms.

"The aspirational Second Amendment is overtaking the judicial Second Amendment in American law," he wrote in the Indiana Law Journal in 2018, a sentiment he repeated in a recent interview with ABC News. "State law is embracing such a robust, anti-regulatory view of the right to keep and bear arms that the judicial Second Amendment, at least as currently construed, seems likely to have less and less to say about the shape of America's gun laws."

Winkler told ABC News the aspirational or "political" Second Amendment has become the basis for expanding gun rights in the last 40 years.

"In the judicial Second Amendment, gun rights advocates haven't found that much protection," Winkler said. "Where they found protection was by getting state legislatures, in the name of the Second Amendment, to legislate for permissive gun laws."

The debate around the Second Amendment (and why some say it might be overrated)

The Second Amendment of the U.S. Constitution reads in full:

"A well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed."

The role of the Second Amendment, like many constitutional rights, is to put limits on what regulations the federal government can pass, and scholars and lawyers have debated its scope since it was ratified in 1791.

Before the U.S. Supreme Court's landmark District of Columbia v. Heller decision in 2008, much of the debate revolved around the meaning of a "well-regulated militia." The Heller decision struck down a handgun ban in Washington, D.C., and established the right for individuals to have a gun for certain private purposes including self-defense in the home. The court expanded private gun ownership protection two years later in McDonald v. City of Chicago, determining that state and local governments are also bound to the Second Amendment.

"The Bill of Rights, by its terms, only applies to the federal government, but the Supreme Court, through a doctrine known as incorporation, has made almost all of its guarantees applicable against state and local governments as well. That's what the question was in McDonald," Blocher said. "But some states have chosen to go above and beyond what the court laid out."

Notably, the court in Heller carved out limitations on that individual right and preserved a relatively broad range of possible gun regulation -- such as allowing for their restriction in government buildings, schools and polling places -- but in many instances, state legislatures have decided not to use the authority that the court has granted them.

"Most states have chosen not to use their full regulatory authority," Blocher said. "If a state decides not to forbid people from having large-capacity magazines, for instance, that doesn't necessarily result in a law. It can be the absence of a law that has the most impact."

It goes back to that widening gap between the judicial Second Amendment as the courts interpret it and the aspirational Second Amendment as used in politics, according to Winkler and Blocher.

"There's a difference between the Second Amendment as interpreted and applied by courts and the Second Amendment as it's invoked in political discussions. And for many gun rights advocates, the political version of the Second Amendment is quite a bit more gun protective than the Second Amendment as the Supreme Court and lower courts have applied it," he said.

Laws based on the 'aspirational' Second Amendment

There are a few laws many experts say bolster gun rights in ways the Second Amendment does not explicitly require.

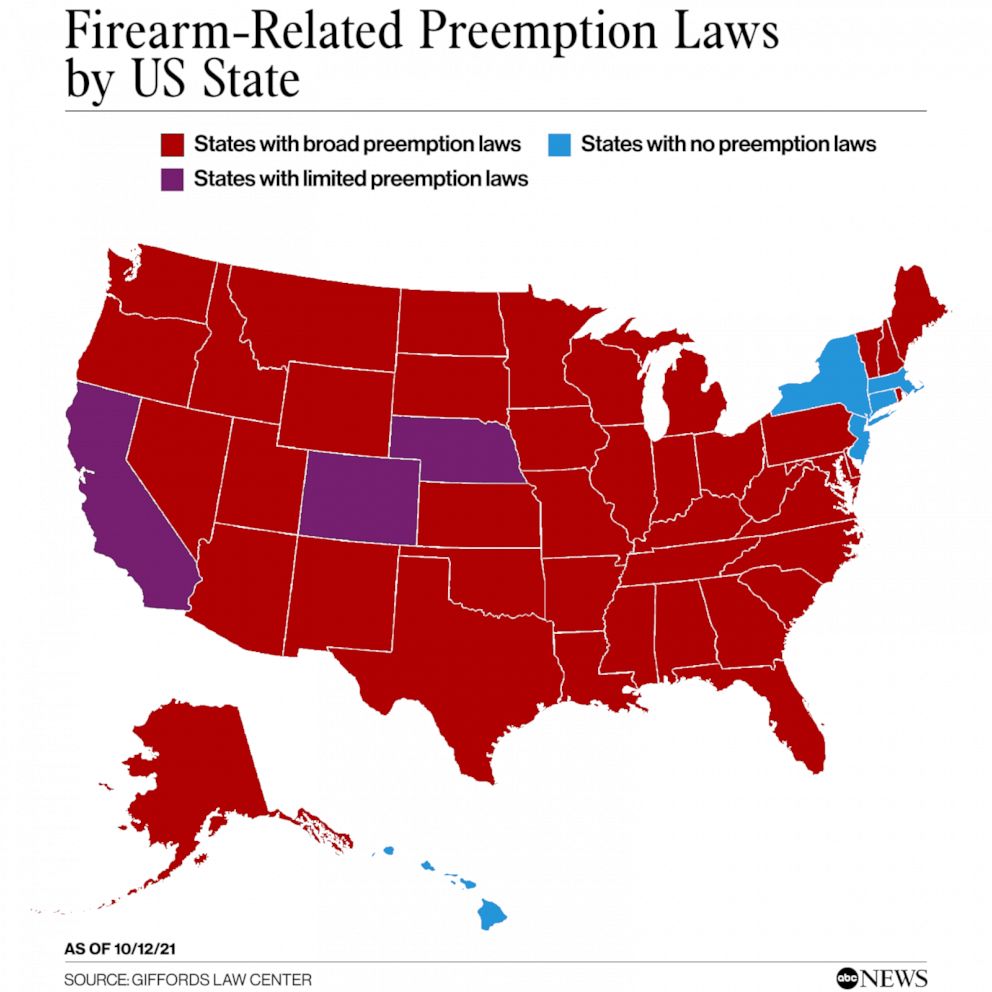

In more than 40 states, preemption laws expressly limit cities from regulating guns -- with some going so far as to impose punitive damages such as fines and lawsuits on officials who challenge the state's rules. This means, even if a highly populated city had overwhelming support to pass a local ordinance regulating guns, a preemption law in the state would restrict local officials from taking any action.

After the National Rifle Association formed its own political action committee in 1977, it began targeting state legislatures with the preemption model and found it was a more effective way to bolster the rights of gun owners than going through Congress.

The effort picked up momentum when a challenge, on Second Amendment grounds, to a local ordinance in Illinois banning handgun ownership failed in 1982 -- years ahead of the 2008 Heller decision. So, he said, the NRA raised the specter of Quilici v. Village of Morton Grove to lobby for preemption laws in order to lessen local governments' abilities to regulate guns in the first place.

In 1979, two states in the U.S. had full preemption and five states had partial preemption laws. By 1989, 18 states had full preemption laws and three had partial, according to Kristin Goss in her book "Disarmed: The Missing Movement for Gun Control in America."

"There's been a concerted effort by gun rights organizations to enact gun-friendly legislation in the states. And they do so using the rhetoric of the Second Amendment, even though nothing about the Second Amendment necessarily requires the state to pass such legislation," said Darrell Miller, another expert on gun law at Duke University School of Law.

While a densely populated area with a high crime rate may want to enact stricter gun policies not necessarily suited for other areas in a state, preemption laws restrict local governments from doing so.

For example, in Colorado, a preemption law had prevented cities and municipalities from passing gun regulation measures. Boulder tried to ban semi-automatic weapons in 2018 after a gunman with an AR-15-style rifle opened fire at a high school in Parkland, Florida, leaving 17 dead and surpassing the Columbine High School shooting as the deadliest high school shooting in American history.

There's been a concerted effort by gun rights organizations to enact gun-friendly legislation in the states. And they do so using the rhetoric of the Second Amendment, even though nothing about the Second Amendment necessarily requires the state to pass such legislation.

But a state court struck down the ban on March 12 of this year -- 10 days before a 21-year-old man with a semi-automatic Ruger AR-556 pistol killed 10 people at a King Soopers grocery store in Boulder. The judge's decision did not hang on the Second Amendment but rather a violation of Colorado's preemption law.

Colorado in June became the first state to repeal its preemption law -- a move gun-regulation activists such as those at the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence have hailed as a reflection of what voters want. More than half of Americans support more gun regulation, according to data from recent surveys by Pew Research Center and Gallup.

There's also the presence of "permitless carry regimes," said Jake Charles, another gun law expert at Duke University, which is when legislatures interpret the Second Amendment as giving individuals the right to bear arms in public without a permit, an interpretation the Supreme Court has not made.

In all 50 states, it is legal to carry a concealed handgun in public, subject to varying restrictions depending on the state, but at least 20 do not require permits for either open or concealed carry of firearms, with Texas becoming the latest to enact what advocates call "constitutional carry."

Permitless or "constitutional carry" is not something the Supreme Court's reading of the Second Amendment currently calls for.

Experts say that could change.

In New York state, a person is currently required to prove a special need for self-protection outside the home to receive a permit to carry a concealed firearm. A challenge to the constitutionality of a "may-issue" permit law, New York State Rifle & Pistol Association Inc. v. Corlett, will be heard by the Supreme Court this fall -- the court's first major case on guns in a decade, coming as the makeup of the court swings right due to three appointments from former President Donald Trump.

"There are about half a dozen states which have laws similar to New York's, so if the court strikes it down, we can expect to see challenges to those states' laws in short order," Blocher said.

The partisan debate continues

Allison Anderman, senior counsel at the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, stressed that, in part because of the influence of state statutes, the Second Amendment should not be a barrier to gun regulation.

She also said that because the Second Amendment's political definition is entrenched in the true, judicial one, the debate surrounding it gets muddied up and the passion is, perhaps, misplaced.

"It's a rallying cry. It's easy. It's a sound bite," she said. "But the Second Amendment gets thrown around politically in a way that's not based in law."

It's a rallying cry. It's easy. It's a sound bite.

Blocher agreed and argued the Second Amendment debate is among the most partisan in the nation.

"The gun debate has gone far beyond judicial interpretations of the Second Amendment and these days has much more to do with personal, political and partisan identity," he said.