As Black Lives Matter murals are disposed of or defaced, Minneapolis activists launch effort to preserve the art

Activists are rushing to preserve artifacts of the modern civil rights movement.

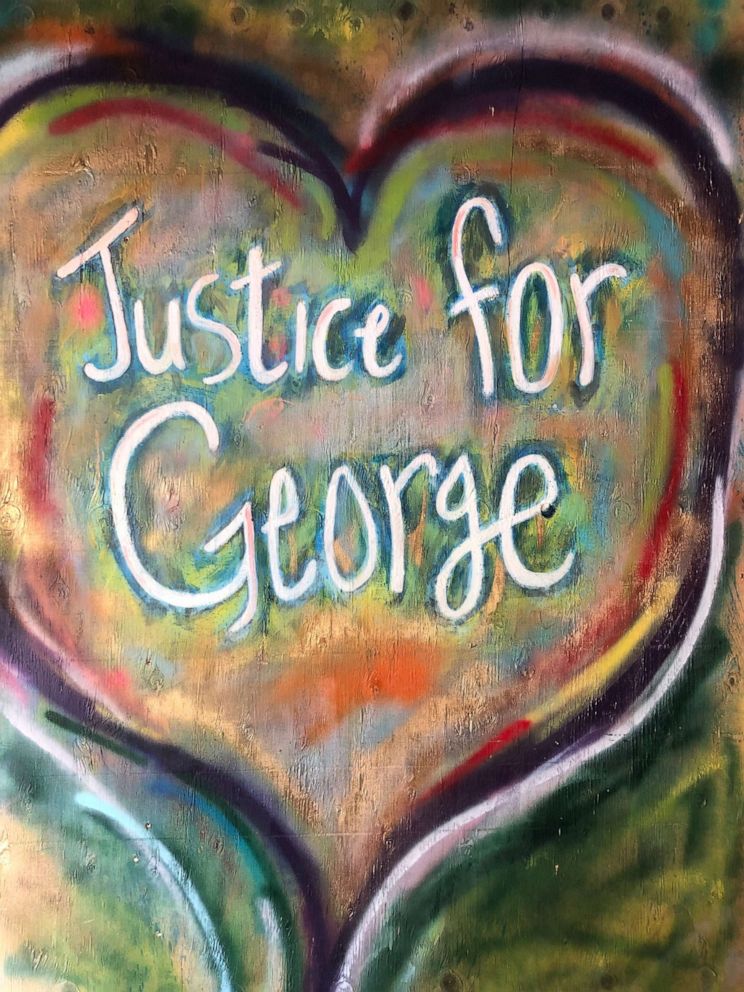

As protests over the police killing of George Floyd spread across all 50 states, Black Lives Matter art popped up on walls, streets, signs and thousands of boarded up businesses that have been shut down due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The murals and graffiti by protesters and professional artists tell a story of pain and resistance – expressions that will become historical artifacts from the largest civil rights movement in U.S. history.

But in some cases, the art has already been destroyed or taken down.

A Black Lives Matter painting calling for an end to racism was vandalized in Fayetteville, North Carolina; a Black Lives Matter painting outside Trump Tower in New York City was defaced with buckets of black paint as the vandals shouted “all lives matter,” a 140-foot colorful mural in Spokane, Washington was vandalized with splashes of white paint and in Lansing, Michigan and Brownsville, Texas artists worked to restore defaced murals of George Floyd. Moreover, as businesses opened up across the country, art-covered plywood started to disappear.

But in Minneapolis where Floyd was killed, local activists have launched efforts to preserve the art and keep it in the community.

How art inspired a movement

As video of a police officer kneeling on Floyd's neck for nearly 8 minutes went viral, Minneapolis native and activist Kenda Zeller-Smith tried to avoid the images.

“I don't really watch those videos anymore only because I feel like they are very detrimental to my mental health and my emotional well-being,” she told ABC News. “I felt really afraid and scared, but at the same time, I wasn't processing my emotions … I just feel like I was numb and I wasn't I wasn't able to emotionally feel much."

Similarly, for activist Leesa Kelly, who has been working with Zellner-Smith on the “save the boards” effort, Floyd’s killing was “a really intense, and a really devastating experience.”

Protesting daily took a toll on her physical and mental health. “I would have days where I couldn't get out of bed,” Kelly told ABC News.

But a few days later as Zellner-Smith drove to work, a piece of new protest art caught her eye and the emotions it elicited allowed her to experience a “really powerful” and “uplifting” moment.

“It wasn't a big, colorful piece it was something more just straight to the point. And I remember that was like the first time, you know, in my car that I felt something -- like really felt something that wasn't these weird kind of gray area emotions,” she said.

“I felt like we've been hurt and I felt like people this time get it, like it's not just Black people that are watching this video and being like this has happened again and again and again,” she added. "This time everyone has heard and it's our city is heard.”

When Zellner-Smith got to work and shared her experience, one of her co-workers mentioned that she noticed that some new Black Lives Matter art created amid the protests had already been taken down.

It was then that she felt a sense of urgency and created an Instagram account to “save the boards.”

Meanwhile, seeking other ways to support the protest and keenly aware of the power of visual art, Kelly said that she also became intrigued by the idea of preserving the murals honoring Floyd.

Kelly launched her own project, “Memorialize the Movement,” and has since connected with Zellner-Smith to join efforts in saving the art.

“[These] beautiful elaborate murals have been an expression of grief. It's been a way for Black people to cope with what's happening, and to express their pain, their anger and the hope that they have for a better America, for a better Minneapolis,” Kelly said.

Keeping the art in the community

Over the past couple of months, Zellner-Smith has been working with other activists to track down artists and convince businesses to donate the art instead of getting rid of it. She has been picking up the plywood art in a truck and has so far, collected more than 40 pieces in a warehouse. Zellner-Smith hopes to find a home for the pieces – one that would keep them in Minneapolis and accessible to the city’s Black community.

“I feel like that art just deserves to be here and serve as a reminder of our power as a community,” she said, adding that it’s important to preserve all forms of expression and not just the “pretty” art because the authentic messages of expression were the pieces that “really started my healing process.”

Meanwhile, Kelly said she has collected 30-40 boards, which make up six or seven large murals.

She said that she felt it was critical for history to be recorded and documented through these murals for people to be able to visualize what had happened, and thus gain a deeper and better understanding of these historically significant demonstrations against systemic racism.

The artwork speaks to the severity of the situation, Kelly continued, and therefore, “we need the story told in a way that people will absorb it. But not in a way that makes them feel comfortable, they don't need to feel comfortable. They need to know what's happening.”

Zellner-Smith and Kelly’s long-term plans for the plywood murals is still in the works. They, alongside several other organizations, and activists across Minneapolis, are working to find a long-term solution to exhibit and preserve the art permanently.

But both women stressed the importance of the art remaining accessible to the Black community in Minneapolis.

“If all of a sudden this stuff disappears, and it goes into these spaces, you know, that are generally predominantly white spaces, or these institutions, it takes away from the people that don't have access to get over there,” Zellner-Smith said.

“Our pain, our suffering and our healing is not something to be bought, and it's not something to be put on display for others outside of the community,” she added. “… I didn't want people to be coming to pay or not pay, but to look at something that is a really raw, real and current representation of our pain and our trauma.”

Kelly said that she reached out to the Minnesota African American Heritage Museum and Gallery, the only Black-owned and operated museum in Minnesota, to see if they would be willing to host an exhibit of the murals, and “tell the story the way that it needs to be told, which is really honest and really raw and told by Black people.”

“This is something we're still facing every single day. And so we need to tell that story in a way that makes people understand that this is an ongoing issue, and it needs a solution,” Kelly said.