How new gun laws could stop some future would-be mass shooters

Most of the recent deadliest shootings involved legal guns.

Laws that have been passed in the aftermath of some of the most extreme instances of gun violence in the U.S. would not have necessarily prevented previous shootings, according to an ABC News analysis.

For example, while much focus has been put on curbing the illegal sale of guns, an analysis of all 17 shootings over the last two decades where 10 or more victims died shows that each of the massacres involved legally-purchased guns.

By contrast, other specific legislation – like the banning of bump stocks and the creation of extreme risk protection orders – could potentially have played a role curtailing more than six of the shootings.

"When you have an epidemic, you can’t look at it and say ‘what is the one thing ever that is going to solve the problem?’ It’s always a multitude of solutions," Kris Brown, the president of Brady, the group formerly known as the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence, told ABC News.

"It’s my view that just given the fatalities, or the value of [a] life, preventing one of these is well worth while. You may not prevent them all and we probably won’t, but we can prevent many," she said.

Friday marks Gun Violence Awareness Day, and states across the country are considering legislation to curb gun violence. Looking back at mass shootings of the past, what laws could have prevented them?

How the shooters get the guns

There have been three mass shootings over the past 20 years where guns were first purchased legally, and were then obtained by the shooters who were under-age and would have been too young to procure a weapon on their own.

That was the case in Columbine, where the guns were bought by so-called straw purchasers, meaning people who are legally allowed – and in this case, old enough – to buy guns who buy them with the intention of selling them to people who cannot buy them directly.

The Sandy Hook and Sante Fe High School shooters both used legally-purchased guns taken from their parents.

The other case where the shooter was able to use a gun that they didn’t buy, and that was in Parkland, Florida, but in that instance, the shooter also had guns of his own, which he legally bought.

The remaining 14 shootings involved guns that were legally obtained by the shooters themselves. That was true in San Bernardino, the shooting at Washington’s Navy Yard and the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting, among others.

Background checks

The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that between February 1994 and December 2015, there have been 3 million cases where a background check has denied someone from getting a gun. Of the denials, some later go on to be approved to purchase a firearm.

David Chipman, a senior policy advisor at gun violence prevention advocacy group Giffords and former ATF special agent, and other advocates say these checks have kept an untold number of guns out of the hands of potentially dangerous people.

But in some cases the background check didn't work, and information that might have prevented an individual from getting a gun was not shared.

The shooting at a church in Sutherland Springs, which left 26 people and an unborn child dead, prompted a review by the FBI and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) because that shooter should have been prevented from legally obtaining a weapon because he had previously been convicted of a crime in military court.

And officials confirmed to ABC News that the shooter at Pulse nightclub in Orlando, who killed 49 people, had been interviewed by the FBI three times prior to the shooting in connection to two other cases, but that information would not have shown up in a background check because the cases were closed.

"Reasonable people would agree we can’t predict how many" incidents have been prevented by stopping people who fail background checks from legally obtaining guns, said Chipman.

"But could it be one? A hundred? A thousand? Knowing how just one person can do so much damage we would assume on a number of occasions something was prevented by that or delayed," he said.

Can a judge intervene?

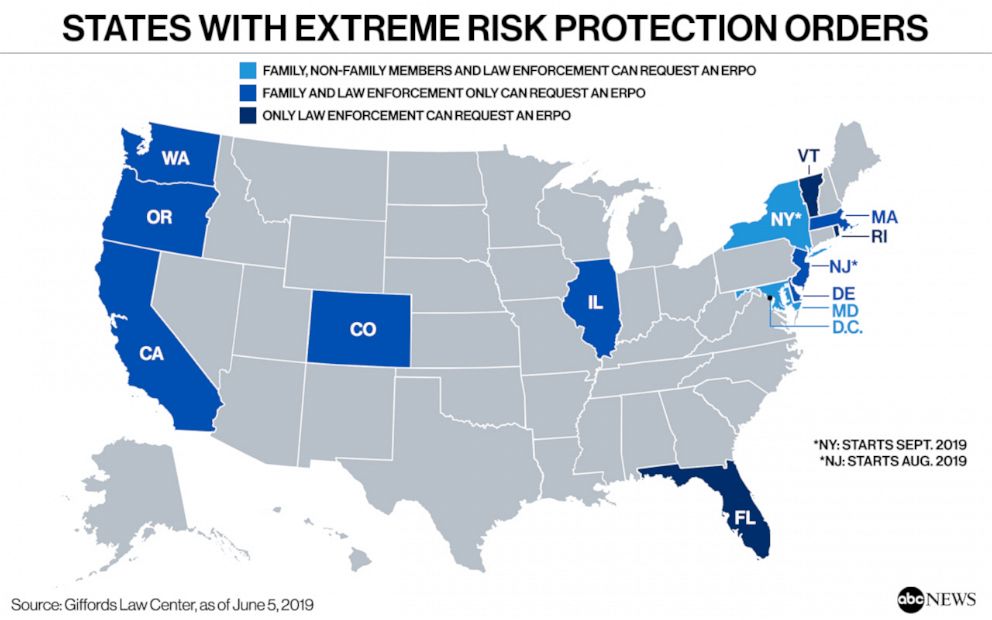

Another possible solution that has been taken up by various states is the creation of extreme risk protection orders (ERPOs), which -- though the specifics differ state to state – allow for law enforcement officers, family members or community members to report concerns about a gun owner. A judge can then decide that an individual’s guns be taken away temporarily, regardless of whether there is a protective order in place.

So far, 13 states and the District of Columbia have some form of ERPO in place, and similar laws will go into effect in New York and New Jersey in August and September, respectively.

It is impossible to say with complete certainty which shooters would have warranted enough cause for alarm before the shooting to prompt an ERPO, should one have existed in their state, but Brown said that cases could be argued for the shooters in Virginia Tech, Sandy Hook, Columbine and the Aurora movie theater shooting.

There is one that’s she’s certain about, however: the alleged Parkland shooter, who has not yet gone to trial.

Brown said that "there were so many signs on social media, from educators, from other students," about the former student, who is charged with killing 17 students and educators at Marjory Stoneman Douglas.

"He is precisely the kind of profile that would be the kind of profile that an extreme risk order would be issued by a court," she said. "Had a similar law been effect in Florida that could have been prevented."

Instead, Florida was one of the states that has since put ERPOs into effect after a massacre.

Slowing the carnage

Another action that came after a deadly wakeup call was the Trump administration’s banning of bump stocks, devices that allow a semiautomatic firearm to shoot more than one shot with a single pull of the trigger. The shooter in Las Vegas who killed 58 victims used such devices in the October 2017 massacre, and the tools were eventually banned in December 2018 and the law went into effect in March.

Restricting the speed at which a shooter can fire has also been addressed by states which limit high-capacity magazines, which Brown said is not only helpful in that it will slow down the shooting but also because it provides an opportunity for people to fight back against the attacker.

Brown called the reloading period "one of the more dangerous times for the shooter."

Chipman agreed, pointing to such an interlude as the time when someone was able to attack the attacker who opened fire at an Arizona grocery store in 2011 where then-Rep. Gabby Giffords and others were injured and six were killed.

For his part, Chipman likened the idea of preventing gun violence to that of preventing public health crises.

"People take the flu shot because they want to raise their chances of not getting the flu. It’s not perfect," he said, noting that some people who do get the flu shot can still get the flu.

"It’s not perfect, but there do seem to be some firearms-related policies that attempt to limit the damage when someone chooses to act out with a gun," he said.

"I don’t think we should shy away from policies that would provide progress rather than perfection," he said.

Editor's note: This article has been updated.