DNA holds promise in finding fugitive Lester Eubanks but FBI rules, privacy questions loom

Marshals hope DNA from Lester Eubanks' biological son will present new leads.

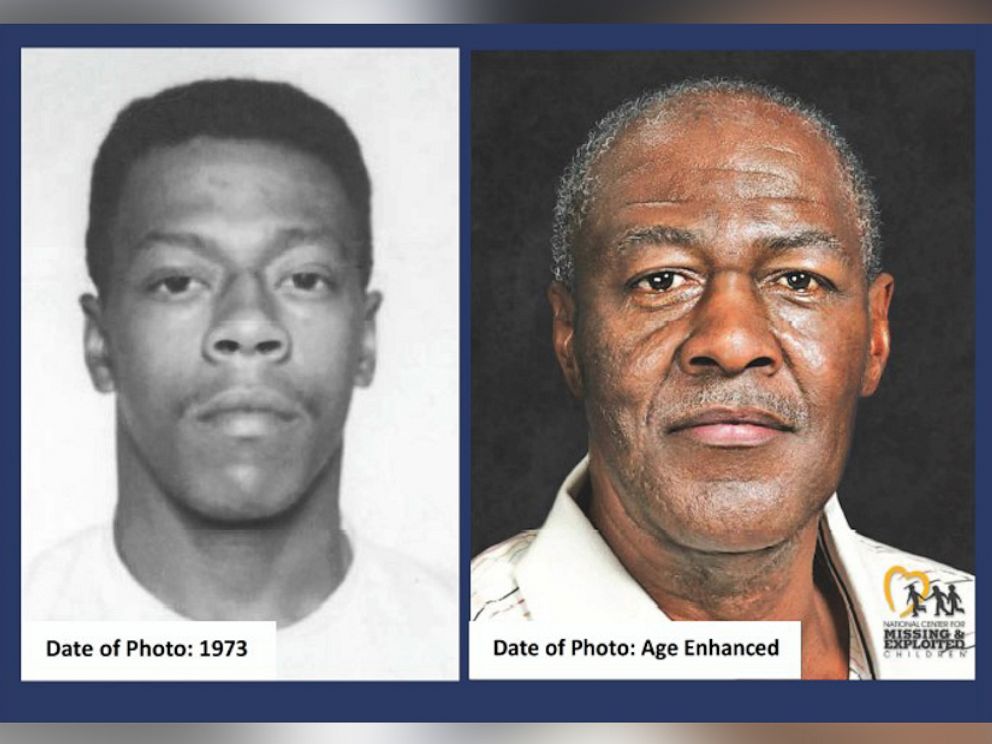

This report is part of the ABC News podcast, "Have You Seen This Man?," hosted by 'The View's' Sunny Hostin. The podcast follows the U.S. Marshals' ongoing mission to find Lester Eubanks, a dangerous convict who escaped from police custody in 1973 and has never been found.

The U.S. Marshals believe DNA collected from escaped child killer Lester Eubanks' biological son could be the key to unearthing new clues to the fugitive’s identity or location.

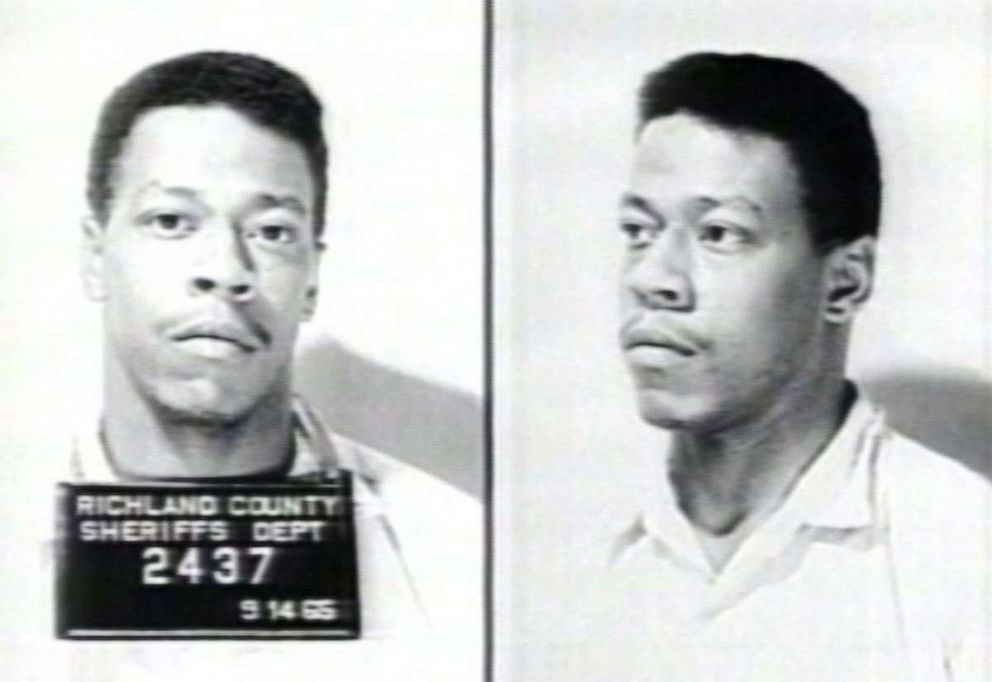

Eubanks, who was convicted of the 1965 murder of 14-year-old Mary Ellen Deener, has been on the run since 1973 after he escaped police custody. At one point, he sat on death row at the Ohio State Penitentiary and remains one of the U.S. Marshals’ most wanted fugitives to this day.

The ongoing manhunt for Eubanks is the focus of the ABC News podcast, “Have You Seen This Man?”

The Marshals have been trying to gain approvals to compare his biological son’s DNA against samples of DNA collected from unsolved crime scene evidence around the country in hopes that it will yield a match and offer hints to Eubanks’ new identity or recent location.

“We’re going to do everything within our legal means to uncover the identity that Lester Eubanks is utilizing,” said Peter Elliott, the U.S. Marshal for Northern Ohio.

As the Marshals have broadened their search for Eubanks, they have encountered a complicated legal landscape governing the use of DNA and so-called “familial searches” to assist in criminal cases.

Henry T. Greely, director of the Center for Law and the Biosciences at Stanford University Law School, said the challenge is getting the sample into the FBI database for review, when the FBI policy prohibits searches using a relative’s DNA.

“I think the first problem is how to get it into the database to begin with,” Greely said.

The FBI would not make available the person in charge of the nation’s criminal DNA database, Thomas F. Callaghan, for an interview. A spokesman instead provided a copy of the current FBI policy, which states: “Familial searching is not currently conducted at the national level or performed by the National DNA Index System.”

Natalie Ram, a University of Maryland law professor who is a leading expert on the laws surrounding DNA data and privacy, said “Familial searches are a touchy subject.”

“The federal government has a policy in place that they do not permit familial searches,” she said.

Ram said the policy is intended to prevent law enforcement from overstepping during an investigation, and violating the rights or privacy of someone who is merely related to a criminal suspect, but not under any suspicion themselves. She said the goal is to avoid seeing innocent people coerced into providing DNA that could be held and used over time in future investigations.

In the Eubanks case, the man who provided DNA has asked ABC News not to identify him. He believes his late mother was raped by Eubanks. He told ABC News he wants to see the Marshals find Eubanks and bring him to justice.

Some legal experts believe this case could open the door for the FBI to make a rare exception to the policy that prohibits searches using “familial” DNA.

“This case is very unusual,” said David Kaye, a Penn State Law professor who studies the use forensic science and genetics in criminal cases.

Kaye said the federal law that led to the creation of the national DNA database does not prohibit searches using genetic samples from relatives. But every state contributes its DNA repository to the national database, and some states have restrictions against those types of “familial” searches. Because each state’s rules are different, the FBI prohibition is intended to take the approach least likely to run afoul of state laws.

Still, Kaye said, there is room for exceptions.

“I’d argue it’s permissible to conduct familial searches at least if there are privacy safeguards in place,” he said. He said protections could be imposed so the biological son’s sample could only be used for the purpose of searching for Eubanks and nothing else.

Erin E. Murphy, a law professor at New York University, said she also believed the circumstances of the Eubanks case may allow for DNA to be used in a national fugitive search. That’s because DNA from Eubanks’ biological son would not be used so much to conduct a familial search, as to construct a profile of the fugitive himself.

By peeling out the parts of the biological son’s genetics that trace to his father, his DNA could become a substitute for his father’s – and using that profile to try and match Eubanks to unsolved crimes would be “groundbreaking,” Murphy said.

And the person whose profile is being predicted – Lester Eubanks – would be required to turn his DNA over to investigators, if they had him in custody – the same as would be required of any other convicted murderer in Ohio, she said.

Whether the DNA sample would produce solid new leads is impossible to predict. But Greely said a search could be worthwhile.

“It is scientifically plausible that a comparison of a biological son’s DNA (if he is a genetic son) to unsolved profiles would turn up hits if the father had been the source of a crime scene DNA sample,” Greely said. “ You might get a lot of false positives … but when you are looking for leads, false positives are common.”

Listen and subscribe to the "Have You Seen This Man?"on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, iHeartRadio, Pandora, Spotify, Stitcher and TuneIn.