Family shines light on US prisoner exchange program that rounded up Japanese Latin Americans

Japanese from Latin America were rounded up and traded to Japan for U.S. POWs.

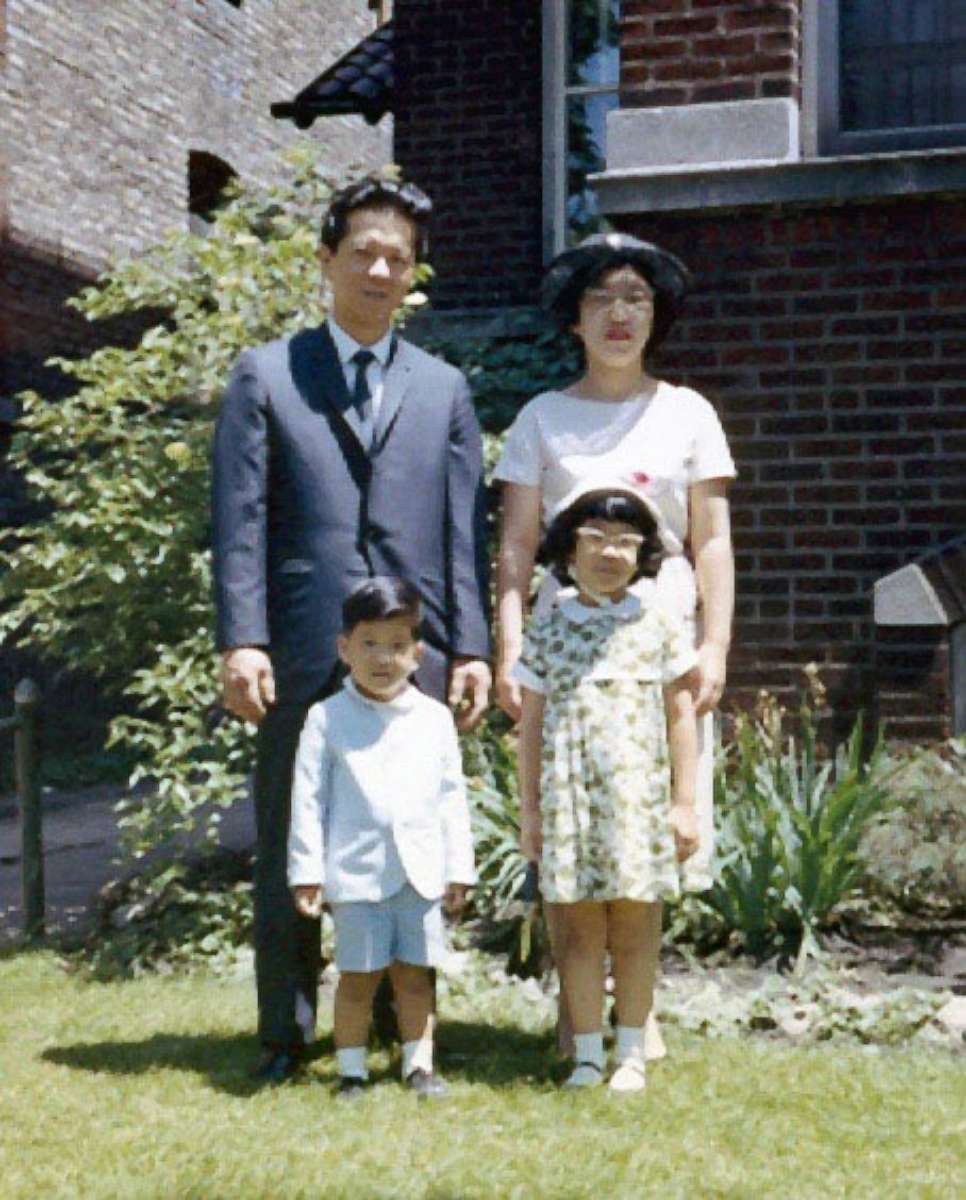

Isamu "Art" Shibayama enjoyed an idyllic childhood in Peru -- fishing on Sundays with his father and going to baseballs games and taking ballroom dancing lessons with his brothers and sisters. Summers were spent by the beach in lush Callao.

A second-generation Japanese Peruvian, Shibayama, his parents and five siblings, were comfortably based in Lima, where his parents operated a textile importing and manufacturing business. They lived in a house with servants and maids, and were driven around the capital city by a chauffeur. They were, by most accounts, enjoying a peaceful and prosperous life, until -- without warning -- the entire family was taken into custody during World War II.

Along with 2,000 other Latin Japanese -- the majority of them from Peru -- the Shibayama family was detained by police and shipped to the United States as part of a little-known prisoner exchange program under the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration.

Immediately after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt issued Presidential Proclamations 2525, 2526 and 2527, which authorized the U.S. government to detain "potentially dangerous enemy aliens," according to information provided by Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library.

The FDR administration furthermore, "on the basis of hemispheric security," offered to intern allegedly dangerous enemy aliens living in Latin American countries on unsubstantiated charges.

More than 15 Latin American countries accepted the offer and deported a total of 6,600 individuals of Japanese, German and Italian descent to the U.S. for internment.

Threads of history

Shibayama was 13 years old when his grandparents -- also living in the port city of Callao -- were captured in 1942 and forcibly transported to Seagoville, Texas. They were used in a hostage exchange and ultimately shipped back to war-torn Japan, where they lived out the rest of their lives.

"My father spent his summers with them, they were very close, and he never got to see his grandparents again," Art Shibayama’s daughter, Bekki Shibayama, said.

This marked the beginning of an arduous journey for the Shibayama family whose stories -- and so many others -- are threads weaving their way into the fabric of the nation's emerging Asian American history, one seldom taught and, until now, little known.

A letter exchange between then-U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull and Roosevelt, dated Aug. 27, 1942, showed a discussion about exchanging American citizens in countries under Japanese occupation by sending "out Japanese in the same quantity," Hull wrote.

At the end of the correspondence Hull offered his support to continue the hostage exchange agreement and efforts to "remove all the Japanese from these American republics countries for internment in the United States," adding, "It should borne in mind that any removal from South America will require the use of a vessel for several voyages between the west coast and New Orleans."

Shibayama’s father, who turned himself in when he found out the police had taken his wife and daughter, boarded the U.S. Army transport ship Cuba along with his family for a 21-day journey to New Orleans.

Upon arrival in the United States, their traveling documents were seized immediately and the U.S. government declared them illegal aliens. They then took a train to Crystal City, Texas, where they were held in prison camps until the end of the war.

'Honorably discharged'

Initially, the Peruvian government did not allow the family's return given the widespread anti-Japanese sentiment in Latin America.

Still deemed illegal aliens, the U.S. threatened to deport them to a war-ravaged Japan, a country Shibayama and his siblings had never known. His family fought deportation with the help of attorney Wayne Collins of the American Civil Liberties Union and in the end only a handful managed to return to Peru.

Those that stayed in the States accepted sponsorships from Seabrook Farms, a vegetable packing farm in New Jersey. After working there for years, the Shibayama family eventually settled in Chicago.

To his surprise, Shibayama was drafted by the U.S. Army as an illegal alien in 1952 and was honorably discharged two years later.

Still stateless, Shibayama continued to struggle to obtain his citizenship, even after serving in the military for a country that did not recognize him as one of its own.

"What’s so maddening is that they didn’t want to come here, the U.S. government forced him to come here. They were stranded here with no country," Bekki Shibayama told ABC News.

When he brought his case to the immigration office in Chicago they said they had never seen a case like his and ultimately advised him to leave the country and re-enter legally in order to become a permanent resident, Shibayama recalled in an archived interview with Densho in 2003.

He later found out his family’s and friends’ cases were all treated differently. For example, two of his friends who were brought the U.S. on the same boat and drafted into the Army received their citizenship and residency in the same year Shibayama’s application was denied. And some members of his family didn’t have to re-enter the country like he did.

There was no rhyme or reason, and nothing was ever explained, Shibayama said. He described it as an inconsistency resulting from a government’s lack of sympathy and responsibility.

'Something could happen again'

Even after Shibayama finally became a citizen in 1970, "he still felt vulnerable, a sense of insecurity that something could happen again to his family even though they’ve done nothing to warrant it," Bekki said.

Shibayama’s quest for redress from the U.S. government began after he and his family were denied of the reparations offered to interned Japanese Americans as part of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988.

The reparations were only eligible to U.S. citizens or residents at the time of internment, and the Shibayama family was of course neither.

"How can I be illegal when we didn't want to come here in the first place and the government brings us here, forces us to come here and bring us at gunpoint?" Art Shibayama said in the Densho interview.

The U.S. government eventually reached a settlement of $5,000 for each interned Latin Japanese American, one-fourth of the compensation Japanese Americans received, with no formal apology or recognition.

Along with several other families who felt the offer was inadequate, Shibayama opted out of the settlement and proceeded with his own lawsuit. Without success in the courts, they filed with the Inter-American Commission for Human Rights (IACHR) in 2003. The group received a hearing in Washington, D.C., in 2013.

A 'zest for life'

Sixteen years later, the Shibayama family is still waiting for a ruling.

Natsu Taylor Saito, 63, a professor of international and immigration law at Georgia State University -- whose own father was a World War II internee -- told ABC News that although there is no way for the IACHR to enforce its judgments in a meaningful way, their win might have a tremendous political impact.

Unfortunately, Shibayama passed away last year without achieving his goal, but his legacy will live on through his children, who have vowed to continue to fight for full acknowledgement of their internment and equal justice.

Bekki said she would like her father to be remembered for his "unwavering fight for justice and his courage to stand up to the U.S. government to hold it accountable for its war crimes against the Japanese Latin Americans."

Calling her father quiet, funny and loving, Bekki said that -- despite everything he suffered -- he always had a "zest for life."