The fire station on the front lines of California's homelessness crisis: 'We're trying to stop the bleeding'

In L.A. County, about 60,000 people live on the streets.

Paramedic Scott Lazar, a 16-year veteran of the Los Angeles Fire Department, is used to treating the same person, sometimes on the same day, on Skid Row.

"Deja vu, yeah, it's every day down here," Lazar told "Nightline" as he treats a man for an overdose, as he did just the day before.

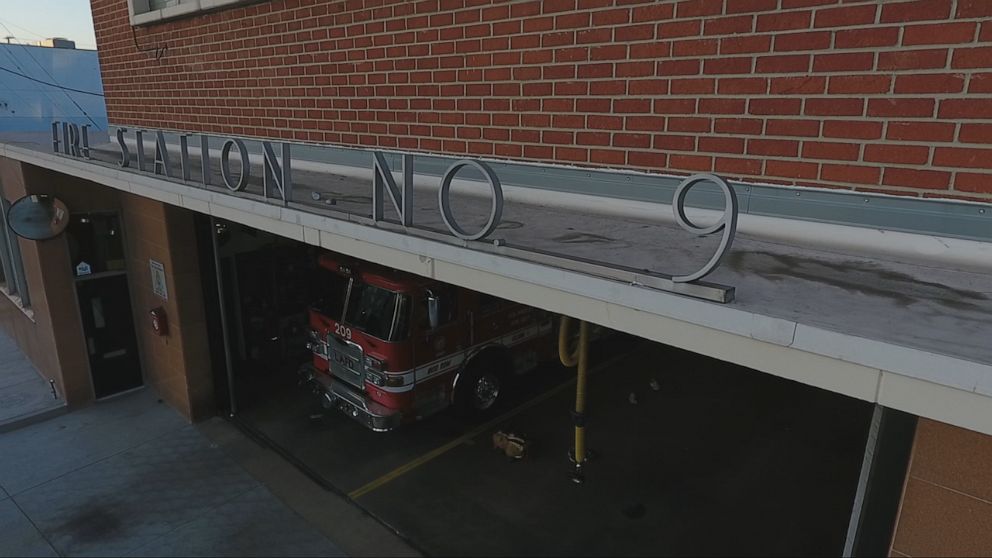

Over five months, "Nightline" got an exclusive look at life at Lazar's LAFD Station 9, rare access to the day-to-day operations of this team and a glimpse into daily life for this city's most vulnerable. Station 9 is one of the busiest fire stations in the country, receiving an average of 80 calls a day -- mostly to treat those living on the street in L.A.'s well-known Skid Row.

Watch the full story on "Nightline" TONIGHT at 12:35 a.m. ET on ABC

Lazar and his partner, Mike Contreras, are members of the fast-response vehicles at the station. Their job is to dart ahead of fire engines to assess the situation and gauge the required resources.

It's been described that each homeless person is like a lock with its own unique key. There isn't a single solution that works for all of them. It's something the firefighters have come to know.

During one of our embeds over the summer, on Lazar's third overdose case of the morning, he said he recognized the man. He'd cut open the man's jeans pocket to ensure he wouldn't be stuck by needles when he hoisted the man into a gurney.

"That is an everyday occurrence. If I work tomorrow, I'm pretty sure I'll [see] him again tomorrow with the same problems," he said. "He didn't get the right locksmith, maybe one day he will."

There are nearly half a million people experiencing homelessness nationwide -- many in California.

In Los Angeles County, about 60,000 people live on the streets, right beside the luxury and glamour of Hollywood. On Wednesday, Gov. Gavin Newsom called the issue "a crisis. This is a state of emergency."

But potential solutions are stalling as fears over disease and public safety clash with the realities of mental illness, addiction and poverty.

Last week, Newsom proposed a $1.4 billion plan to address this as debate in the state rages over long-term solutions.

Amid the turmoil, there's a quiet domesticity at the station. Sharing meals, cleaning gear, fitting in quick workouts -- it's a brotherhood.

"[We] pretty much live here," engineer Mark Tostado told "Nightline." "We live here a quarter of our time -- so I do live here. This is our home away from home."

LAFD Medical Director Mark Eckstein said responders at this station are exposed to extraordinary danger every day.

"They're exposed to needles, violent crime, communicable diseases you think would only exist in third-world countries, and they're literally running nonstop," Eckstein said.

Yet some, like Tostado, keep coming back. This is his 11th year at the station and his second tour of duty.

"You have to want to be here ... to see what's going on here ... feces, throw up, needles and overdoses and death -- most people don't see that at all," Tostado said. "I can't even count how many times I've seen death. And you just get used to it."

Over several months with Station 9, there was a fair share of misery, but also glimmers of hope -- like a man who goes by the name Mango. He's become a self-appointed aide to the firefighters, stepping out into crowded streets to stop traffic so fire trucks can zip through. Sometimes he'll even clear the city's street gutters.

"He helps us out a lot here," Tostado said.

Mango gave "Nightline" a tour of the Skid Row neighborhood, where he was often greeted as if he were the mayor. He helped a disabled woman get a blanket. She broke into tears. Despite not having teeth, she tried to convey someone had run over her foot.

"It's warfare out here," he said. "These people out here need to be in shelter."

Moments later, Station 9 got another call and "Nightline" rushed back. Tostado told us there was a report of a disturbed woman. When "Nightline" arrived, four firefighters were talking to her when, suddenly, she started to swing at them. They subdued the woman, who was still kicking and crying on the sidewalk, as gently as possible by borrowing a security guard's handcuffs.

Tostado said he sees situations like this "weekly."

"I mean, it's not their fault, a lot of times it's a psych issue or they're doing drugs. And it's an effect of the drugs," he said.

That woman would be taken to the emergency room, which is part of the problem, Eckstein said.

"Having paramedics roll on someone who's hearing voices, who endorses suicidal ideation, take 'em to an E.R. with no mental health professionals, how does that help?" he said. "If someone's intoxicated, what do we do in the E.R.? We check for any treatable medical or traumatic conditions, which often involves very expensive, redundant testing. And we basically let 'em sober up and they go back on the street. Do it all over again."

Eckstein said it's a good thing there are new resources "but we haven't solved the problem."

"We're trying to stop the bleeding. We're trying to get help for the most vulnerable people in our society," he added.

LAFD Chief Ralph Terazas said one of the problems is regulatory. Paramedics can only transfer patients to the emergency room, without the option of transfers to mental health facilities or sober houses, which might be more appropriate.

"It's crazy to me. Because police officers, with minimal medical training, have that authority now to take 'em wherever they want. But our paramedics, who have much higher medical authority, are not allowed to do so ... because it's not compliant with county protocol," he explained.

That's what's causing the backlog at hospitals and sapping the city's budget, Terazas added. He and L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti are now lobbying the state for those changes.

The crew here at Station 9 notches wins every day, as they say, treating each individual without bias because their patients are human beings, and this is the job.

"Imagine going treating someone who's covered in dirt, human waste. They respond [to calls from] people with these problems every day and they treat them with the same level of respect as a CEO working in a high-rise two blocks from here," Eckstein said. "That is quite noble and quite admirable. And they do it day in, day out."