5 key takeaways from Texas Senate's hearing on Uvalde shooting

Texas DPS Director Steven McCraw called the police response an "abject failure."

A top law enforcement official in Texas testified Tuesday that efforts by law enforcement to end the Robb Elementary School mass shooting sooner were an "abject failure," laying much of the blame at the feet of a local police chief who waited well over an hour to breach a classroom door and kill the gunman.

Texas Department of Public Safety Director Steven McCraw appeared before the Texas state Senate panel investigating the May 24 shooting in Uvalde, where a gunman killed 19 students and two teachers in one of the deadliest school shootings in U.S. history.

McCraw's testimony, supported by an updated timeline of events that he said was based on police body camera and surveillance videos, and a transcript of police communications during the rampage, appeared to offer the most complete version of events to date -- and heightened scrutiny of Pete Arredondo, the embattled school district police chief in who was the on-scene commander during the shooting.

Here are five key takeaways from Tuesday's hearing.

Officers could have 'neutralized' shooter within minutes

In a striking rebuke of the responding authorities, McCraw claimed that enough officers and equipment had arrived on the scene within three minutes to "neutralize" the shooter, who had by then entered the classroom and begun firing on students and teachers.

"The only thing stopping a hallway of dedicated officers from entering room 111 and 112 was the on-scene commander," McCraw said, referring to Arredondo, who McCraw said "decided to place the lives of officers before the lives of children."

McCraw's testimony shattered previous claims that officers who responded immediately lacked the necessary equipment and weapons to breach the doorway, instead opting to wait as more resources arrived.

"One hour, 14 minutes and eight seconds. That's how long the children waited and the teachers waited in rooms 111 and 112 to be rescued," McCraw said. "And while they waited, the on-scene commander waited for radios and rifles. Then he waited for shields. Then he waited for SWAT."

"Lastly, he waited for key that was never needed," said McCraw.

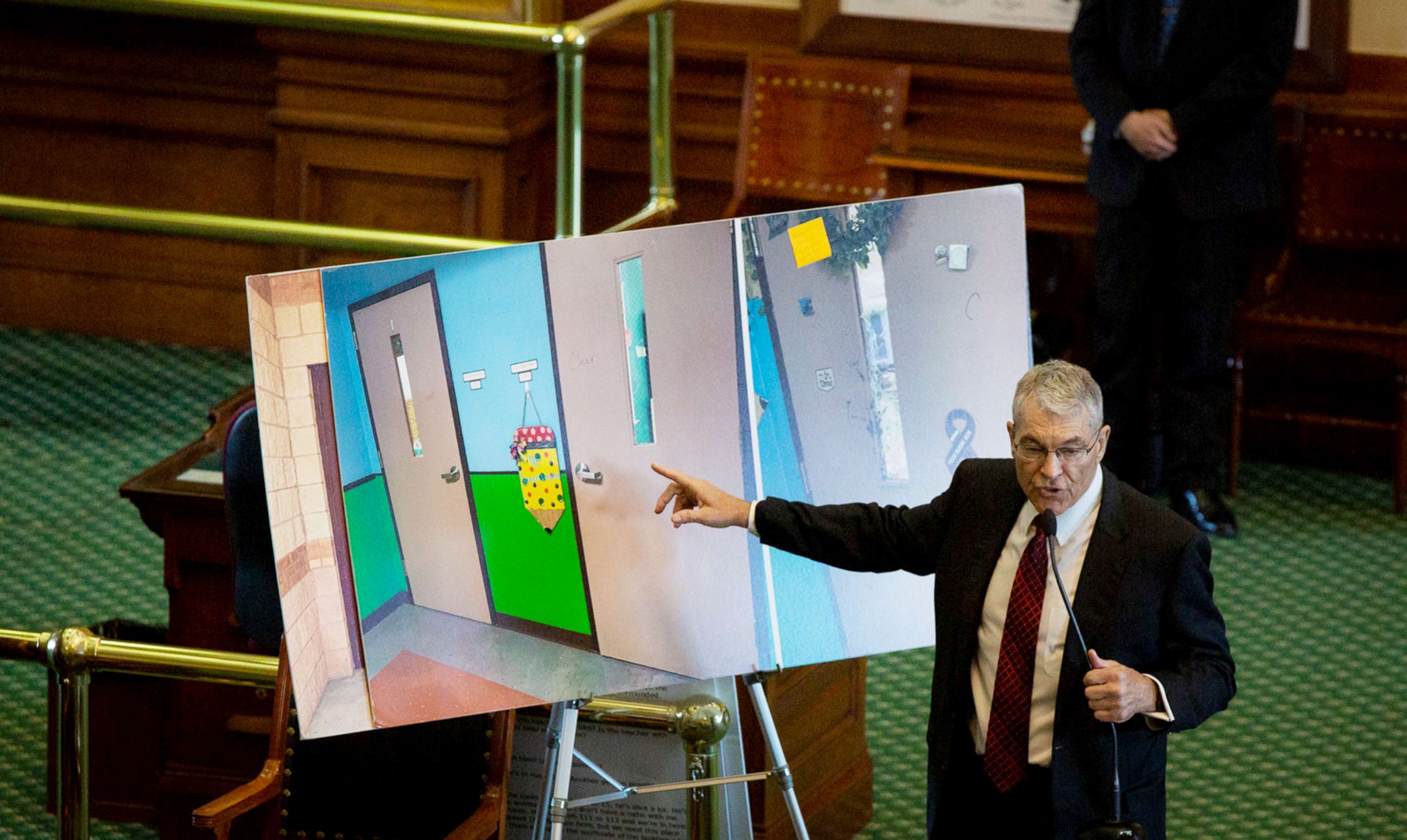

The door to the classroom may not have been locked

McCraw sought to clarify some confusion over whether the exterior and interior doors used by the gunman to enter Robb Elementary School were locked -- and whether officers even needed keys to breach the classroom where the gunman had barricaded himself.

According to McCraw, the door to the classroom containing the gunman could not be locked from inside, meaning it was likely unlocked for the duration of the shooting.

"I have great reasons to believe [the door] was never secured," he said.

McCraw later said it appears that officers on the scene never checked whether the door to the classroom was unlocked, even as they waited for additional equipment to breach it and worked to secure a set of keys.

"How about trying the door and seeing if it's locked?" McCraw said he would ask the officers who responded first.

Communication failures crippled law enforcement response

A staggering series of communications failures plagued the police response at Robb Elementary, McCraw said Tuesday, including problematic radio reception inside the school building.

McCraw confirmed previous reporting that Arredondo arrived at the school without a radio. Later, according to McCraw, local police and Border Patrol lost radio communication signals inside the school.

Those circumstances ultimately led Arredondo and others to communicate with dispatchers on their cell phones, McCraw said.

"Cell phones did work, obviously, inside the school," he said. "It's just the portable radio devices that first responders had didn't."

State police 'don't have authority' to overrule on-site commander

Multiple state senators challenged McCraw to explain why arriving officers from larger law enforcement agencies did not take over command from Arredondo when they saw he was waiting to breach the classroom.

"I don't see why y'all didn't take command once you had DPS agents inside the hall pushing to breach the door," one state senator asked McCraw. "Lives would have been saved."

"They don't have authority by law," McCraw shot back.

McCraw explained the normal procedure is that the agency with the most direct order of expertise should take command -- and that the school district police chief, in this circumstance, was the best person to deliver orders.

"I'm reluctant to encourage -- or even think of any situation -- where you'd want some level of hierarchy, where a larger police department gets to come in and take over that type of thing," McCraw said.

Arredondo is under growing pressure to provide his account

New revelations from the Senate hearing put an additional spotlight on Arredondo. The embattled school district police chief spent Tuesday in the neighboring Texas House chamber, where he testified behind closed doors for nearly five hours.

A lawmaker on the state Senate panel called on Arredondo to appear before their committee in a public setting.

"I challenge this chief to come testify in public as to what happened here," said Sen. Paul Bettencourt, a Republican on the state Senate committee. "Don't go hide in the House and talk privately -- come to the Senate, where the public … can ask these questions."

Arredondo has largely remained silent in the four weeks since the shooting, save for an interview with The Texas Tribune earlier this month.

"Not a single responding officer ever hesitated, even for a moment, to put themselves at risk to save the children," Arredondo told the paper. "Our objective was to save as many lives as we could, and the extraction of the students from the classrooms by all that were involved saved over 500 of our Uvalde students and teachers before we gained access to the shooter and eliminated the threat."

Arredondo, the Texas Department of Public Safety, and other law enforcement agencies that responded to the shooting have declined a long list of media requests and requests from families to release underlying records.

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this story said it was Texas state Sen. Brian Birdwell who called on Pete Arredondo to appear before the Senate committee. That comment was actually made by Sen. Paul Bettencourt.