Maryland wildlife refuge fights to protect American history from climate change

Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge is facing the effects of sea level rise.

While extreme heat waves, wildfires and devastating flooding bring attention to the impacts of climate change, some parts of the country are fighting more pernicious effects that threaten both protected ecosystems and important landmarks of American history.

Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge is a wetland in the outer banks of Maryland established in 1933 as a protected area for bald eagles, osprey and several species of migratory birds. The government officials working to protect it say they can see the impacts of climate change in the refuge every day. As the ocean continues to warm and sea levels rise, the water is turning marshes into lakes and allowing invasive species to take over the ecosystem.

But the pressure to protect Blackwater is about more than just the plants and animals that live there. It also has deep roots in American history. Harriet Tubman is connected to multiple sites in the area, including the town where she was born, the general store where she was hit in the head after refusing to stop an enslaved boy from escaping and multiple locations she used when leading slaves to freedom on the Underground Railroad.

"These are the very forests. If Harriet Tubman were here today, none of this landscape would have looked different to her at all," said Deanna Mitchell, the superintendent of the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Historical Park.

Those forests are now also feeling the impact of climate change. The trees can't survive the saltwater intruding on the marsh, and more and more forests are dying, turning into what U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Biologist Matt Whitbeck calls "ghost forests."

"For many people, many visitors, if they come to the refuge, they go around our wildlife drive and they look to the south and they see this big body of open water. And it's beautiful. You know, we have pelicans out there, we get tundra swans out there in the winter, the sunsets, and it's just lovely," he said.

"But once you understand the factors that cause this big expanse of open water, it's a little alarming. So when the refuge was established in 1933, that was all the vast expanse of tidal marsh. So we had black rails, we had nesting black ducks. We had all of this habitat that has since been lost to open water."

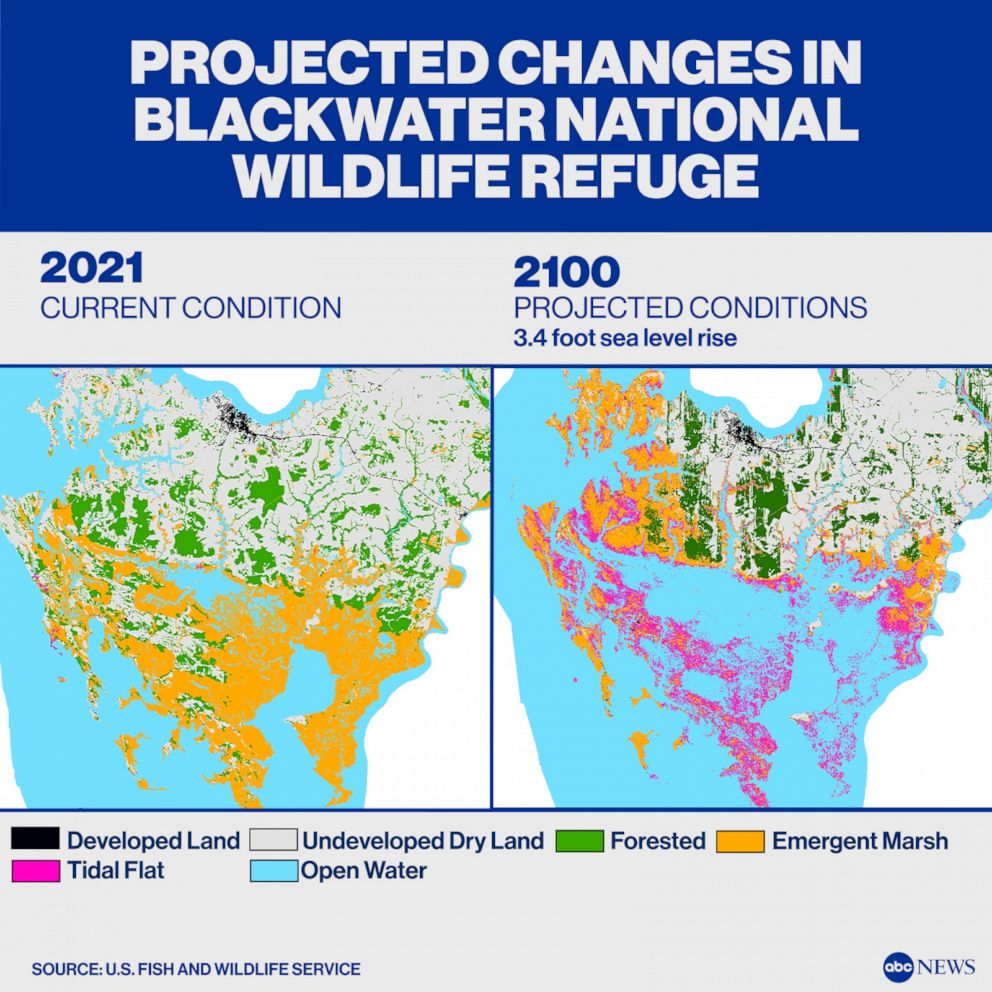

Whitbeck said 5,000 acres of tidal marsh at Blackwater have been converted into open water since the refuge was created, and encroaching saltwater has killed acres of forests and made irreversible changes for native species. The Fish and Wildlife Service expects sea levels around Blackwater will be 3.4 feet higher in 2100 than they are now, meaning most of the marshlands visible now will all be underwater.

The Fish and Wildlife Service has worked to restore marsh areas and is researching ways to manage the ecosystem, but Whitbeck said they won't be able to stop all of the changes they're seeing in the marsh as sea levels continue to rise and the saltwater makes it harder for native species to survive.

Just in the last year, a team of archeologists from the Maryland Department of Transportation announced they discovered the site of a cabin belonging to Harriet Tubman's father, Ben Ross, where Tubman lived as a child and worked with him as an adult.

The agency recently purchased the 2,600-acre property where they found the site, because they were concerned it could be completely flooded before they were able to find and preserve what remained of the property.

"Sea level rise was already beginning to take away that particular site and that history. So if we had waited, if we hadn't been able to begin this, even a couple of years, we might never have found it. So we found it just in time in a surprise area, in an area that was definitely being impacted by sea level rise," said Marcia Pradines, the head of restoration efforts for wildlife refuges around the Chesapeake Bay.

Pradines and other federal officials are charged with making difficult decisions about how to prioritize the fight against climate change in protected wildlife refuges, including sometimes accepting that not every impact of climate change can be stopped or that they have to adapt their approach to determine what parts of the ecosystem will be able to survive. The federal government has adopted new guidance called Resist, Accept, Direct, acknowledging that they can no longer protect the country's natural resources from every impact of climate change.

"I am very confident that at the end of my lifetime, Dorchester County will continue to be one of the largest expanses of tidal marsh in the Chesapeake Bay," Whitbeck said.

"The trick is what kind of marsh will it be, and what plants and animals will live in that marsh? And that's what we're still sorting out."

While federal and state officials work to balance the current impacts of climate change with the parts of Blackwater they can protect, they say they are focused on preserving the history for generations to come.

"The reality is we are dealing with climate change, and we are seeing the impacts of sea level rise to some degree," Mitchell said.

"So I would say probably by the end of the century, things will start to change in here, you know, pretty much. But while we can do it and while we have the ability, we need to try and do as much as we can to protect what we can for as long as we can."