Parents of college student who died after taking fentanyl want to shed light on 'ugly subject'

Madeline Globe purchased what she thought was Xanax, but it was the opiate.

Alden Globe said it felt like a drive-by shooting.

He didn't know much about fentanyl, about overdoses linked to the synthetic opiate. He'd never needed to.

"Why would I learn about this?" he said, thinking back. "It's never going to be something that we would be involved in."

Then a $5 pill laced with the opiate killed his 21-year-old daughter, Madeline. She thought she was buying a Xanax.

Now Globe and his wife, Susan, of Steamboat Springs, Colorado, are working on getting others to understand how dangerous fentanyl can be.

"A $5 pill ended her life in a couple hours. It was like a drive-by shooting almost. It was that shocking to us," Alden Globe said in a telephone interview with ABC News on Thursday. "That suddenness, the lack of understanding about what a dangerous decision that was" is what the Globes hope to shed a light on for others, he said.

Deaths involving synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, increased from around 3,000 in 2003 to more than 30,000 in 2018, according to research published in RAND in 2019.

"In fact, synthetic opioids like fentanyl are now involved in twice as many deaths as heroin," according to the report.

Others studying fentanyl have reached similar conclusions.

Journalist Ben Westhoff, who published the book "Fentanyl, Inc.: How Rogue Chemists Are Creating the Deadliest Wave of the Opioid Epidemic" in 2019, claimed that the opiate now kills more Americans annually than any drug in history.

The reason for that is the drug's immense potency, said Dr. Brian Fuehrlein, an associate professor of psychiatry at the Yale School of Medicine. Fentanyl is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine.

"People don't really appreciate how powerful it is," Fuehrlein told ABC News in a telephone interview Wednesday. "Just a very small amount is all you need for a lethal dose."

He noted that while other opiates dosages are measured in milligrams, fentanyl is dosed in micrograms. And because of how cheap it is, it's often manufactured to look like other high-demand drugs.

"Dealers are now selling pills that are designed to look like the other things, like Xanax or Valium," Fuehrlein said. "The person who's buying the drugs think they know what they're buying, but it's actually fentanyl. Dealers are making a huge profit."

Madeline Globe was not a fentanyl user. If anything, her parents said, the senior at the University of Colorado Boulder always was the one taking care of her friends.

"She used to complain to me that she was tired of being the responsible one, helping her classmates," her dad said.

Susan Globe said that although she'd spoken to her daughter about over-indulging or other drugs, such as cocaine, she had no idea her daughter took Xanax, nor did she understand how fentanyl was making its way into other drugs.

"This is why we're sharing Maddy's story, because the school didn't understand that back in 2017. It was such a new phenomenon that the authorities, the attorneys, the doctors, no one had an understanding of what was beginning to happen," Alden Globe said.

Dean Cunningham, a public safety information officer at the Boulder Police Department, told ABC News that Madeline Globe purchased the pill from someone on the street, and that her friends similarly purchased pills, but theirs didn't contain fentanyl.

"You can order some of these drugs -- fake, real or not -- and you just don't know what you're getting," he said.

It's this danger Alden and Susan Globe said they hope to make others aware of.

Both parents think the conversation has improved since their daughter's death, with more people discussing potential dangers, but they still worry whether it's enough.

"There's a lot of information out there, but I think people don't want to know about it. It's an ugly subject," Alden Globe said.

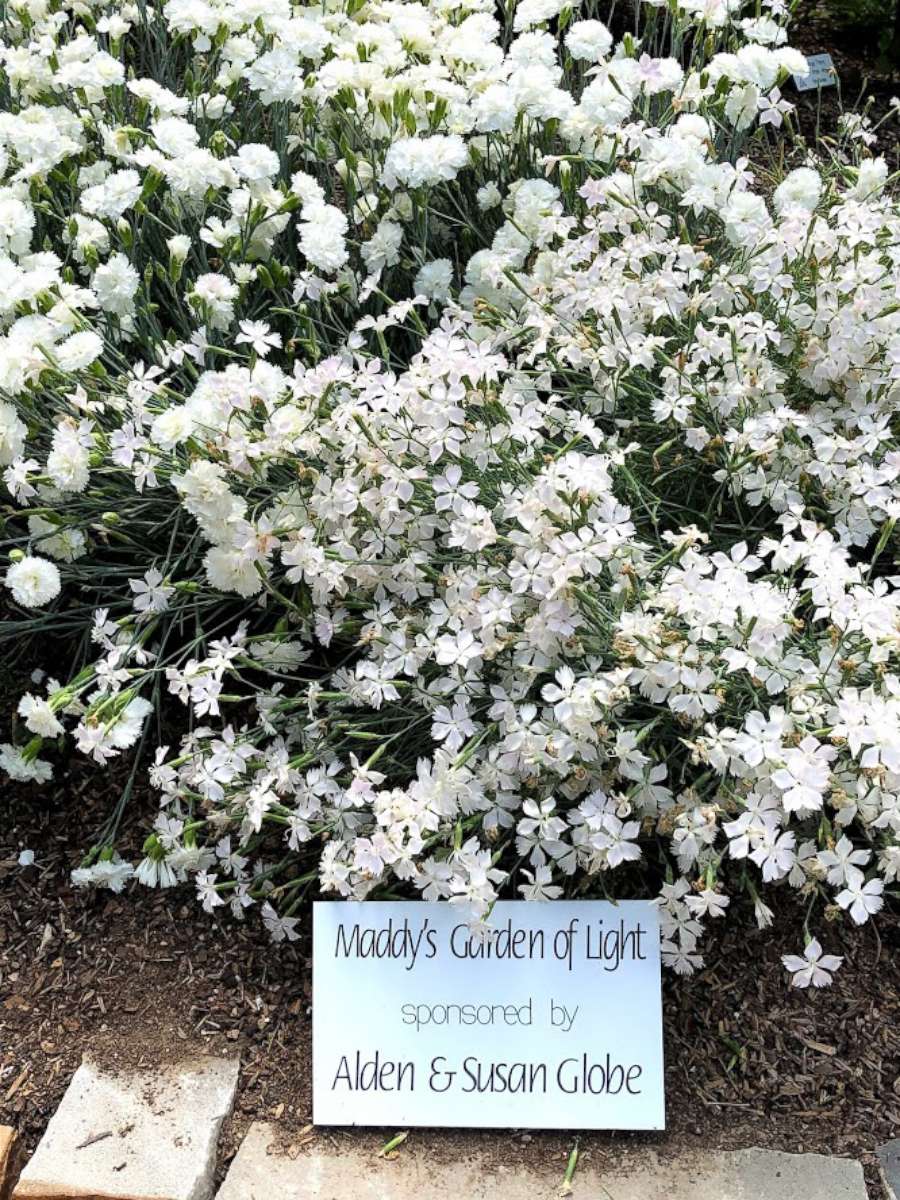

In the two years since Madeline Globe's death, they have been able to speak out more as time goes on. Susan Globe also has started a garden in her daughter's honor at the Yampa River Botanic Park. She named it "Maddy's Garden of Light."

"I chose that because she is our light," she said. "She still remains our light."

The pain, though, remains.

"Every day, we think about this. Our home is empty," Alden Globe said. "We used to have a lot of high school- and college-aged girls here with Maddy, and now it's very quiet. Nobody is coming over to hang out because she's gone."