Puerto Rico, still reeling from Hurricane Maria, faces major challenges

Hurricane Maria struck Puerto Rico six months ago, and it is still recovering.

Hurricane Maria killed countless Puerto Ricans, caused $100 billion in damages, and in the six months since it ripped through the U.S. commonwealth, caused its people to rethink their political status and relationship with the United States.

Since the storm made landfall near the town of Yabucoa, Puerto Rico, shortly after 6 a.m. on Sept. 20, those three issues have shaped the discussion on the island -- and will play a big part in determining its future.

An elusive death toll

Hurricane Maria pummels Puerto Rico, Caribbean

"Every death is a horror, but if you look at the real catastrophe like Katrina and you look at the tremendous hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of people that died ... 16 people versus in the thousands, you can be very proud of all of your people” President Donald Trump said in Puerto Rico on October 3.

The supply chain of water, food and necessary supplies was disrupted after cell phone towers were destroyed and communications between remote towns and San Juan officials were cut off. Following the passing of the story, the government’s death toll came into question as some believed the death toll was lower in comparison to how devastating the storm was.

Gov. Ricardo Rossello signed an executive order in Dec. 2017 ordering the Puerto Rico Demographic Registry and the Department of Public Safety to review all deaths that have occurred since Hurricane Maria hit in September, "regardless of what the death certificate says."

The death toll provided by the government stands at 64, according to the island’s Department of Public Safety.

Analysis of the island’s mortality shows a spike in the number of deaths after Maria. According to Alexis Santos, director of graduate studies in applied demography at Pennsylvania State University who has studied the daily mortality data from the Puerto Rico government, says there were approximately 1,000 more deaths on the island in the month after Maria.

“The governor has made the case that a lot of things didn’t happen, like asking the federal government for help, because they were saving lives. It is quite a shock ... analyzing the data. In reality, they were not saving lives, either,” Santos said.

“It calls into question what were they doing in the days following the hurricane,” he added.

San Juan’s outspoken mayor, Carmen Yulin Cruz, told ABC News she hoped that the final death toll becomes public because “we owe it to the memory of those people to know. And we owe it to the transformation of Puerto Rico: why they died, and how we can ensure that this does not happen again.”

An independent commission, led by researchers from George Washington University, is expected to release a report on storm-related deaths at the beginning of April.

Restoration and recovery

The restoration of the electrical grid has been key in the effort to restore the island to normalcy. Benchmarks were made early in the aftermath after Rossello announced in mid-October a deadline of December 15 to reach 95 percent of electricity distribution on the island.

The island’s 3.4 million residents were plunged into darkness as Maria made landfall. As of March 17, more than 100,000 customers remained without power in Puerto Rico -– just over 7 percent of the number of customers in Puerto Rico that are able to receive electrical power.

"I am not satisfied that people in Puerto Rico should have to wait that much time for power," the Army Corps of Engineers’ Lt. Gen. Todd Semonite told ABC News in an interview in February. "But I am telling you, there are no other knobs I can turn to go any faster."

Officials expect to see power restoration plateau by the end of the month at 95 percent as contractors attempt to reach some of the most remote and sparsely populated parts of the island.

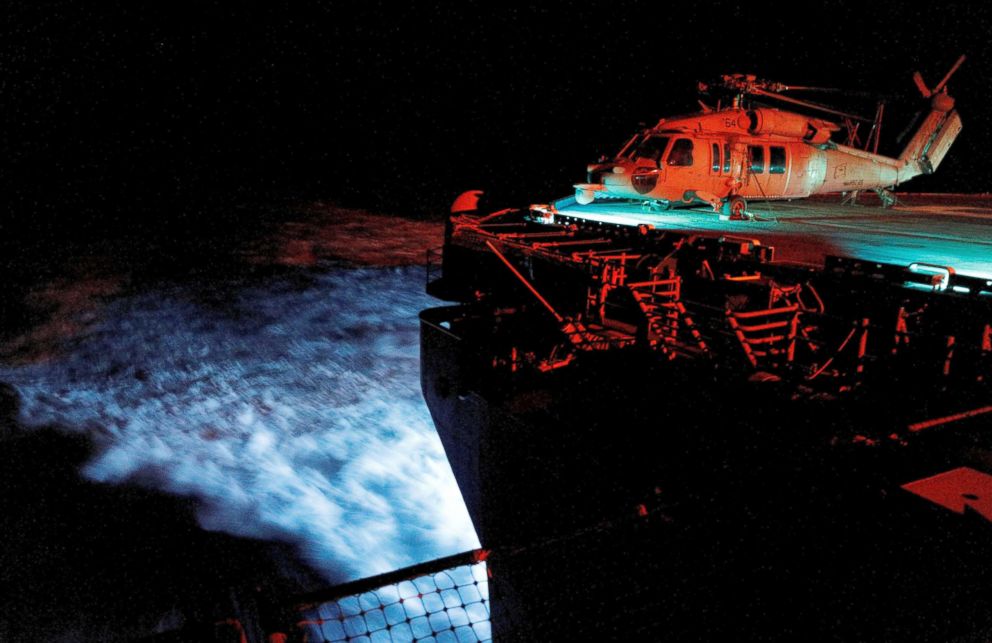

“We can get 95 percent of this done, in say six months, but now we are doing things by helicopter because it is that hard to make some of that happen," Semonite said.

The future of statehood

Even before the storm tore through the island, the status of Puerto Rico has been a controversial issue -- and it has intensified since September. The island is currently considered a territory of the United States –- while they are citizens, Puerto Ricans are not eligible to vote in presidential elections and do not have a voting representative in Congress.

In 2016, Puerto Ricans voted in a non-binding referendum to determine the island's political future; more than 97 percent voted for statehood, though the vote was disputed because of a historically low turnout driven in part by a boycott from opposing groups.

Pedro Rossello, the former governor and father of the current governor, says Maria brought to the forefront a critical issue for the island.

“This is not just the storms. Puerto Rico for the past decade has been in an economic recession or depression. It has acquired the largest public debt in Puerto Rico history. It has developed a chaotic financial structure. That alone is a perfect storm” the former two-term governor said.

“But add to that the situation of two natural disasters, as were Irma and Maria," he added, referring to the hurricane that preceded Maria a few weeks before. "Then you see we are facing [the] greatest challenges in the history of Puerto Rico.”

Yulin Cruz, who once said that pursuing statehood is like “a freed slave striving to become a slave owner,” told ABC News in December that following Maria “it is time for Puerto Rico to reconsider its relationship with the United States.”

“The time [to reconsider the relationship] has long passed, and Maria and Irma made it very evident. We need to ensure that we can plug into the world economy,” she said.