What's next for Puerto Rico after vote for US statehood

Experts doubt that much, if anything, will change.

— -- Puerto Rico's political status as a commonwealth and an unincorporated territory of the United States is unlikely to change anytime soon, despite the Caribbean island's Sunday vote asking the U.S. Congress to make it the 51st state, according to some experts.

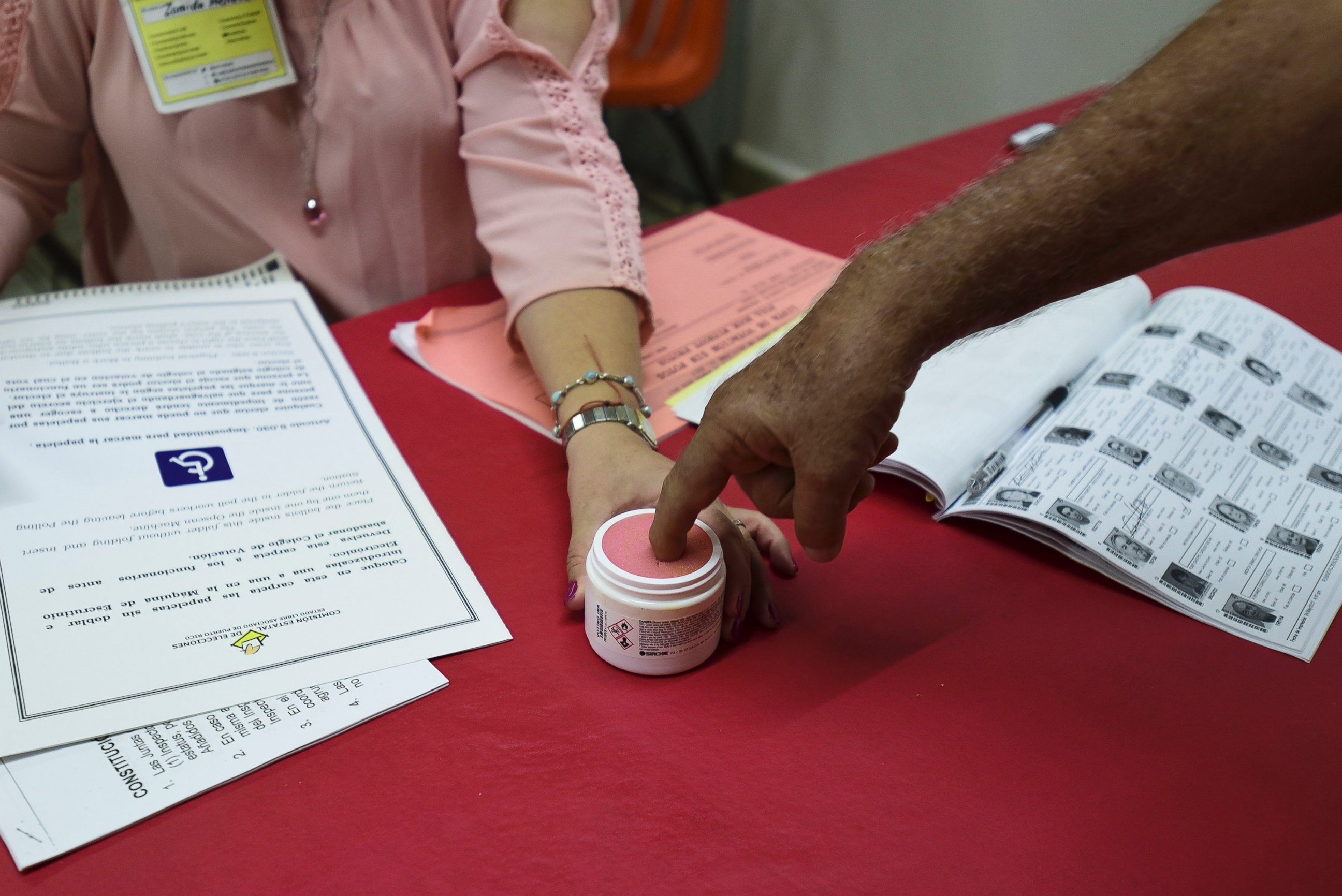

The nonbinding referendum asked residents to choose from three options for Puerto Rico: become a U.S. state, remain a commonwealth or become an independent nation.

A whopping 97 percent of voters chose statehood, according to a tally by Reuters, though less than one-quarter of Puerto Ricans bothered to participate, largely because people who favor remaining a commonwealth and those seeking independence from the United States sat out the vote in protest.

A vote undercut by low turnout

The overwhelming margin of victory in the nonbinding vote is undercut by the knowledge on the ground that Puerto Ricans are far more divided on the notion of becoming a U.S. state than the election indicates, experts on the subject told ABC News.

Amilcar Antonio Barreto, an associate professor of cultures, societies and global studies at Northeastern University in Boston, estimated that a truly representative vote would have given statehood only a small margin of victory, remaining a commonwealth slightly less than 50 percent and total independence a single-digit percentage.

Carlos Vargas-Ramos, a research associate with the Center for Puerto Rican studies at Hunter College in New York, offered a similar estimate and said that these divisions are well known to Puerto Ricans.

"If this result is brought before Congress, the results will be heavily undercut by the reality that many people didn't vote," he said.

Palmira Rios, the director of the graduate school of public administration at the University of Puerto Rico in San Juan, said that while there was palpable debate across the island today in the wake of the vote — much of it on radio and televisions shows — it's worth noting that the struggle for statehood is gaining ground among residents.

"Of the three options, statehood is the only one that has steadily been growing in popularity for 50 years," Rios said.

Republicans unlikely to budge

Puerto Rican statehood would give the island's roughly 3.5 million residents significant representation in the U.S. government, and that, beyond anything else, poses a major roadblock, the experts agreed.

Vargas-Ramos estimated that Puerto Rico would have greater federal government representation than at least 22 current states because of its population — likely five representatives in the House in addition to two senators.

The bulk of them would likely be Democrats, he said.

"Maybe one of the five would be a Republican," Vargas-Ramos said, adding that some districts on the majority Roman Catholic island might vote Democratic because of economic issues but hold socially conservative views.

"Think Jim Webb," Vargas-Ramos said, referring to the moderate Democratic former senator from Virginia who made a failed bid for his party's presidential nomination in 2016.

Also, adding Puerto Rico as a state would bolster the case for Washington, D.C., to become a state, as well as the U.S. Virgin Islands, an unincorporated U.S. territory in the Caribbean.

Both of those, if given statehood, would likely vote Democratic as well, further discouraging the Republican-dominated U.S. government from considering Puerto Rico's bid, according to Vargas-Ramos.

Barreto told ABC News, "Congress is loath to touch the subject" because of politics and called the outcome of a congressional vote "more predictable than a Roman Catholic Mass."

"The debate would start with a 'Thank you for your service,'" Barreto said, referring to Puerto Rico's housing of U.S. military bases. "Then it would be followed by questions about Puerto Rico's Spanish language and culture being incompatible by the Republicans, followed by pushback that the debate had become Latin-phobic."

Barreto said Puerto Rico's government will push Congress to take the vote seriously but that is unlikely to happen.

"Congress is likely to ignore the results," he said.

Vargas-Ramos said, "Congress is unlikely to bring anything to vote unless they expect to get the outcome that they want."