Street artists memorialize Black lives lost to racism and police violence

"Their voices are being heard... They’re being seen for the first time."

Millions of Americans took to the streets this summer to protest the deaths of George Floyd and countless other Black people victimized by racism and police violence. Among them were many who chose to memorialize those lives lost through their art.

Vince Ballentine, a New York City-based street artist and motion graphics editor, has painted several murals during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Over the course of a single day, Ballentine completed a portrait of 23-year-old Elijah McClain with his violin. McClain died in 2019 while walking home from a convenience store in Aurora, Colorado, after police stopped him, placed him in a chokehold and EMTs later gave him a dose of a powerful sedative.

"The part that ravaged me the most was the fact that what he said while he was being brutally murdered were kind words," Ballentine said.

The incident began after police responded to a 911 call in which McClain was described as "sketchy." When they arrived, McClain told police he was walking home. As the incident unfolded, all three officers' body cameras fell off but continued to record audio, in which McClain could be heard explaining himself and pleading with the officers.

“I’m just different. I’m just different, that’s all. That’s all I was doing. I’m so sorry. I have no gun. I don’t do that stuff," he said in the audio recordings as the officers talked among themselves.

Ballentine has been a grade school art for several years. He said McClain reminded him of a lot of the children he's taught.

"I've met a lot of those just young, brilliant minds that are a little different, a little introverted, a little to themselves, but still have these talents and qualities and this love of life."

Ballentine said he made the mural to celebrate "that life that was taken and the lives that are still here that are very similar."

And he's not the only one.

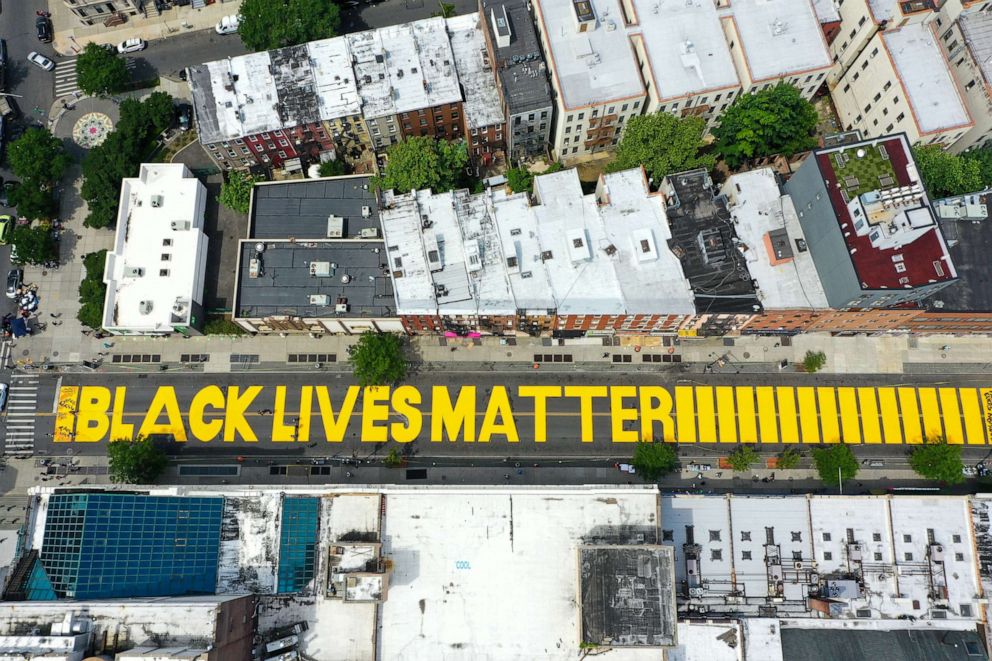

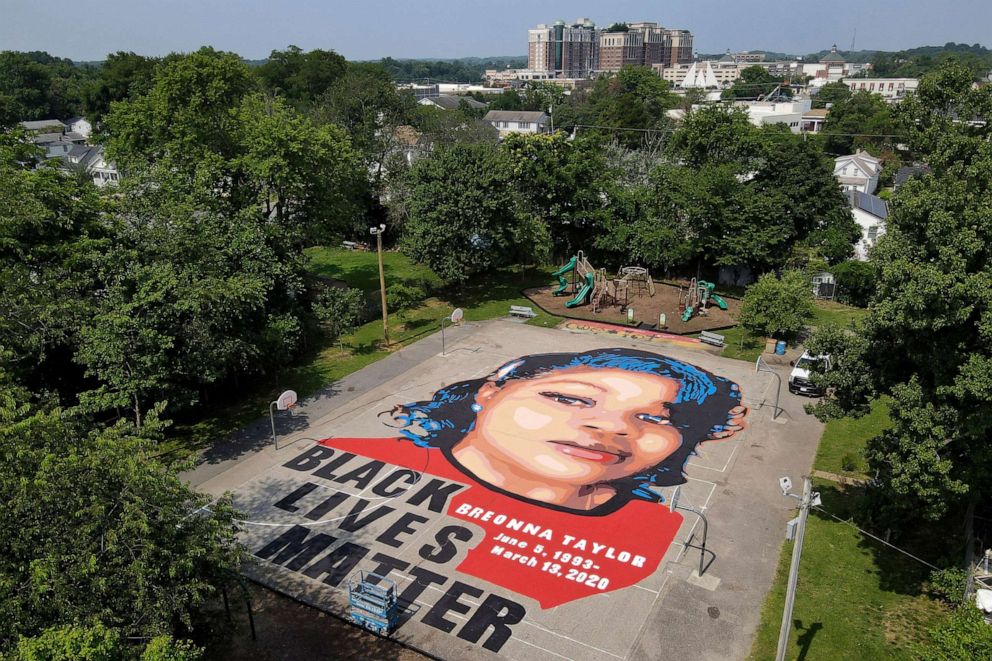

Artists across the country have turned blank spaces in cities emptied by the coronavirus pandemic into canvases to remember people like Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and Sandra Bland, and to emphasize in words spanning city blocks that "Black Lives Matter."

"I think that when cities started to open up, people felt great joy and a great desire to do something and be useful, and to kind of make something beautiful for people," said Rujeko Hockley, assistant curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

While some "Black Lives Matter" murals, like the one in Washington D.C. and Brooklyn, New York, are straight to the point with yellow lettering, others include more intricate motifs and symbolism. In downtown New York City, Sophia Dawson recently designed the "Lives" portion for one mural.

"I started looking at what they did in Seattle, what they did in Harlem [New York City]. I was like, 'Oh my God,'" she said. "It's kind of like a domino effect; a ripple effect happening, right? I think for the communities, I feel like they feel like their voices are being heard -- that they're being seen for the first time."

She said many of the hundreds of people who volunteer to help with installing the murals may not even know how to paint, "but they're showing up to leave their mark." Although a protest may only be a fleeting moment, she says the murals serve "as an active process that continues to go on whether people are in the streets or not."

Dawson isn't new to making this kind of artwork. In 2016, she installed a mural called "Every Mother" in Newark, New Jersey, after the deaths of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling. The piece, the portraits of which were painted separately on parachute cloth, commemorates mothers who lost their sons to police brutality and racism.

Although the piece is now four years old, she acknowledged how relevant it remains after the death of George Floyd.

"Had this happened and there was no pandemic or quarantine, the people would not have time to be on the streets," Dawson said. "People would not have time to do all that they've been able to do. Like, people are literally home for the first time in the moment of an uprising, and I think that's what makes a big difference. … The purpose of the color bars is to literally be the TV screen that says programming is done for today, and it feels like the world is standing still in that way for the first time."

A classically trained artist, Dawson didn't realize her gift until she applied her art to her surroundings.

"I never really thought about art as activism," she said. "But the first mural that I did, I was like 15 or 16. We were transforming a classroom… What impacted me, I think, was when the young people came to see the room for the first time and seeing their eyes brighten up. … So that was the first time I saw the transformative nature of art."

She said she likes making large pieces because of how "in your face" they can be.

"Public art -- murals -- is really bringing art to the people, so I like scale because I like the 'in-your-face' factor," she said. "Also the fact that a regular person who's just walking down the block can see this piece, but also someone who intends to look at art or is interested in my art or is interested in the movement can travel here on their own time."

The art that reflects the racial reckoning happening in the United States today is only the latest in a history of art speaking to the times, Hockley said. Art in public spaces could be seen as far back as the Great Depression and continued to emerge during the Vietnam War era and the AIDS epidemic, she said.

Hockley believes the current moment has reminded people that the power to create change is in their hands.

"I think that this pandemic has really given everyone their sense of being their own superhero," she said. "I think everyone has started to see that … we have the answers in ourselves."

Jessica Goldman Srebnick, owner of Miami's Wynwood Walls, which have become world-renowned for their elaborate and oversized murals, says people are appreciating art differently than they have in the past.

"What we're seeing are these conversations that are making people think," she said. "They're giving people perspective in a different way and they're making people want to act."

With it being an election year, she predicted there will be a lot of art surrounding the topic of voting. "That's something that is really powerful," she said. "And I think that artists today are being seen in a leadership role unlike they've ever been seen before."

Some artists have already taken up that role, including Tristan Eaton of Los Angeles, who recently painted a mural of the political activist Angela Davis seeming to shout, "Vote."

"Angela Davis has a beautiful history of protests and activism in fighting for the freedom of Black people in this country," Eaton said. "So her story should be told and shouted from the rooftops, and we have an election coming up."

In June, Eaton had painted a mural of Martin Luther King Jr. in the same spot. He said it was meant to be "a sign of solidarity," but then it was "met with some blowback" when someone tagged racist slurs over it.

"It's easier to paint a mural of Martin Luther King than it is Malcolm X, because Malcolm X can be a divisive figure," Eaton said. "But I realized that the only people that find him divisive are the people I shouldn't be listening to. … We said, 'OK, if they paint [over] it, we'll come back and paint it again.' And they messed with the wrong person because I love doing this. I love painting. So let's go."

"In graffiti, you paint something, someone else paints over it, [and then] you paint right back over it again and you kind of go to war with each other in creative battle," he added.

Street artists are used to having their work painted over. Hockley says "it comes with the territory."

"Art in public spaces is not always loved… It's subjective. People can like it, people cannot like it. And of course, is it art or is it graffiti? And what does that mean?" Hockley said. "So I think that the fact that people know that it can be removed … comes with the territory in some ways, and I think artists who work in those spaces, whether as muralists, whether as kind of putting up installations in public spaces, etc., they kind of know that … its permanency is not necessarily part of the goal. I would think that that's important -- these walls get painted over and new murals go up."

When Ballentine returned to his McClain mural a few weeks after painting it, he found that during that time, someone had tagged over a corner of it. He pointed out that the person who painted over the mural was "conscious" about not painting over McClain's portrait but rather only on the side.

"A lot of times when you're doing street art, whatever you want to call it, if you leave too much space that doesn't look like it's occupied, somebody's going to come by and say, well, there's enough room for me right here," he said.

Ballentine restored the mural by painting over the tag with a collage of the words, "I'm sorry," the same words McClain told officers several times after vomiting from their restraint.

Ballentine is grateful for the opportunities he's been afforded to paint over the past few months.

"Never in my years of living on this planet has it been advantageous to be a Black painter," he said. "I was painting, but people weren't exactly checking for me. And since this whole thing has started, it's kind of like I'm a commodity now. … People are now responding to my work like they never have before."

As summer comes to a close, many of these artists see it as their mission to continue amplifying the voices of those who feel unheard.

"The world of graffiti is probably the largest secret society on the planet," said Eaton. "Our collective voices are extremely powerful and we have access to the public space … and I expect to see huge movement and a lot of noise from this world of people in the next few months leading up to this election."

Srebnick said the energy and passion that street artists put into their work not only lives for so long as it's on a wall, but that it's also "shared with people that have an opportunity to engage with it."

"The work is supposed to minister to people," said Dawson. "People are supposed to come in front of the painting and if they are hurting because they lost a family member, if they are hurting because of what's happening in their community, they're supposed to be inspired. They're supposed to be uplifted."