Twins make astonishing discovery that they were separated shortly after birth and then part of a secret study

Howard Burack always knew he was adopted, but he never knew he had a twin.

Editor’s note: After our original “20/20” report aired on March 9, 2018, the Jewish Board sent written apologies to the twins who appeared in our program, saying in part, “We recently watched the ‘20/20’ telecast about the separation of twins and we’re deeply moved by the comments you made … we realize that our efforts have fallen short, and that we can and should do more… we feel we must reach out, acknowledge our past error, and set a new moral course for the future.” Some of the twins from the study have since accepted the Jewish Board’s invitation to start a dialogue to “…begin the task of repairing past wrongs and making them right.”

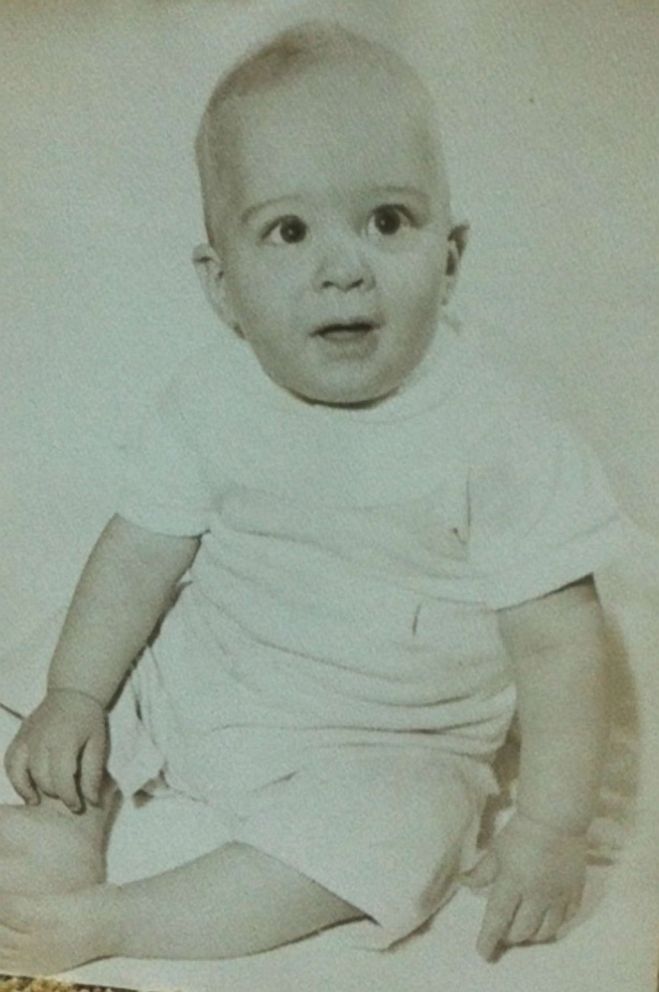

Howard Burack always knew he was adopted.

“I grew up in a nice, upper-middle-class family in a nice, suburban area north of New York City, in Rockland County, and normal childhood, normal whatever, great parents,” said Burack, who was born in 1963.

He told ABC News’ “20/20” that his parents adopted him when he was a baby from Louise Wise Services, a prominent New York City Jewish adoption agency in the 1960s.

But Burack's view of himself as a normal adoptee was shattered when, in his 30s, he made a routine inquiry to the adoption agency, requesting his birth records, and was told that somewhere in the world he had an identical twin brother.

Burack said the staff at the agency, however, told him they could not release his sibling's name until he too requested his records because of New York laws.

“[You] just feel like you’re missing something, just don’t know what it was,” Burack said. “You can’t touch it. You can’t feel it. Something was there.”

Searching for long-lost twins

Lori Shinseki, a documentarian and ABC News consultant, is the filmmaker behind the documentary “The Twinning Reaction,” which has helped Burack and other multiples who were split up get answers about their identical siblings.

The title of her film refers to the special connection twins have by spending so much time together from conception.

“The easiest way to explain the twinning reaction is that it is the twin bond that’s so obvious to us today, in the womb together, in their crib together, as touching and holding each other, looking to each other, interacting from a very, very young age,” Shinseki told “20/20.”

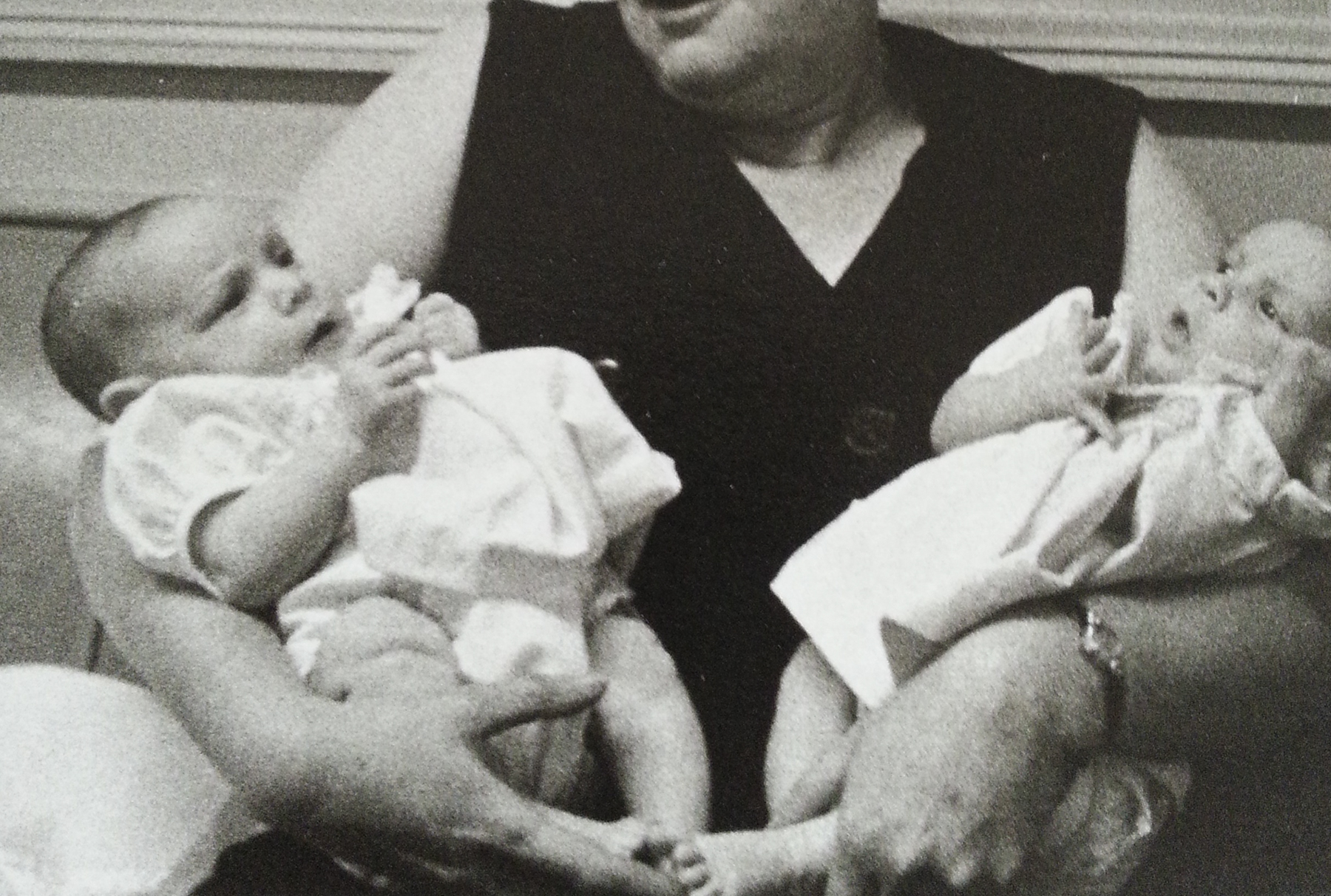

The documentary tells the shocking story of identical infant twins -- and even a set of triplets -- separated and adopted by different families, without Louise Wise Services’ telling the parents that their new addition is a multiple.

While researching for her documentary, Shinseki uncovered a stunning secret about a woman named Sharon Morello. Like Burack, Morello, born in 1966, was also adopted through Louise Wise Services.

Shinseki called Morello’s adoptive mother, Vivian Bregman, who then called Morello.

“[She] says, ‘Some lady just called me to say, you know, she’s doing a documentary and that you have an identical twin sister.' And I said, ‘Excuse me?’ And I hung up the phone,” Morello told “20/20.” “I was in shock. I just couldn’t. It took me hours to call her back to say, ‘All right, what's going on?’”

According to Morello, Bregman said that she'd never been told that Morello was a twin and that she would have adopted twins together, had she known.

“They decided to separate these twins and triplets, place them in different families, and never told the families that they had adopted a half of a twin set or a third of a triplet set,” Shinseki said.

According to Shinseki, it turned out that Morello, Burack and some other children adopted through Louise Wise Services were victims of a double deception: Not only were they separated from their identical siblings, but they were subjected to a secret long-term study by scientists without the clear, informed consent of the adoptive families.

“What they did was they told the families that this baby is in an adoption study. 'If you want the baby, we would like to continue studying the child,' [they said.] And, of course the families would do anything,” Shinseki said.

Like other adoptive parents, Bregman said she was told it was a child-development study.

“We went in and they said, ‘All right, now. She's in a study. If you don't want to be in this study, let us know,’” Bregman said in an interview in “The Twinning Reaction.”

Woman discovers she has a twin she was separated from at birth

Discovering a bizarre and secret study

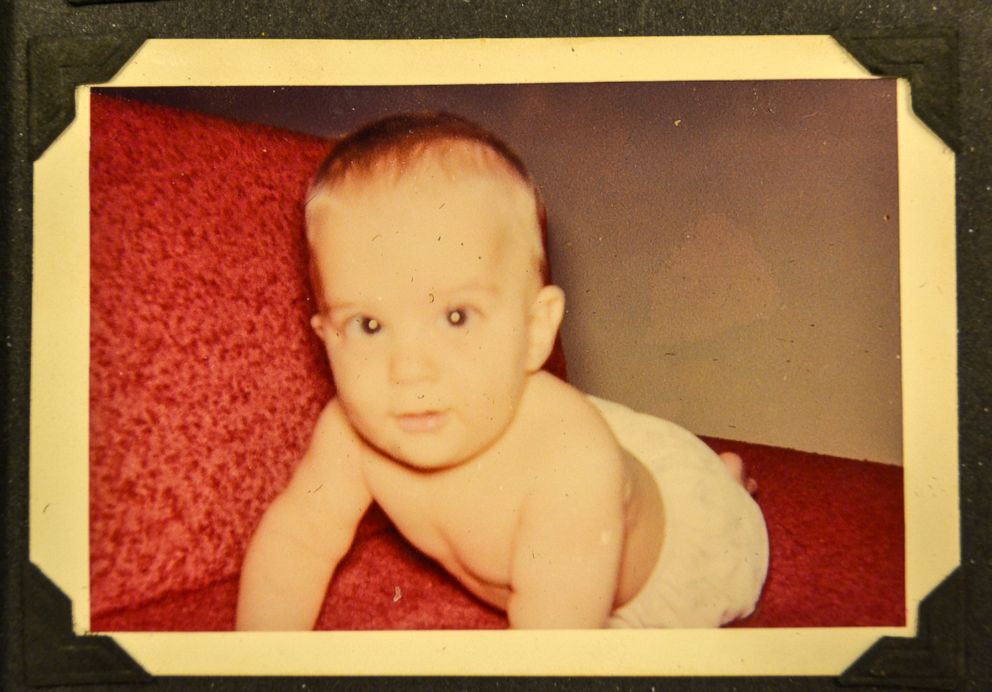

Doug Rausch was also adopted through Louise Wise Services, by George and Helen Rausch.

“Some scientists in the 1960s were deciding to study nature vs. nurture. Evidently they found a way through the adoption agency to place twins with different families. My father and mother were never told that there was a twin brother,” Doug Rausch said in an interview in “The Twinning Reaction.”

“They gave us Douglas and said, 'We'll let you have this child, but we're going to monitor it.' So it was a question of if I say no, they won't give me the child. I think there was a certain amount of coercion to our permitting them to conduct the study,” his father, George Rausch, said in the documentary.

“They made it sound like this was to everybody's benefit to see how smart this kid is, because I don't know him. Here, we're adopting a child we don't know. We don't know his background, but it never dawned on me why they're coming back so many times,” Helen Rausch said during an interview for “The Twinning Reaction.”

The babies in the study are all adults now, but many said they have flashes of memories of odd, intrusive visits from nosy strangers throughout their early childhood, poking into their lives, questioning, testing and filming.

“I do remember just a person coming and I remember like looking at books. You know, they would show me different pictures,” Morello said. “I would have to say what, what did I think that picture was.”

“They would film me and they would make me ride my bike and they would, you know, do this test and that test and I mean it was kind of fun for me at the time, I don’t know. But you know, you get bored with that pretty quick. I’m like, ‘Can I go now?’” Doug Rausch told “20/20.”

“[They did] all kinds of psychology tests and drawing and just looking at things and inkblots and drawings and talking to you and asking questions,” Burack said.

Morello said she and her family never really understood why the researchers were coming to their home.

“My mother was pretty much told: ‘We wanted to make sure things are, you know, things are good with the siblings,’” she said.

“It was fairly stressful in the house when they would come, because you know, your parents are worried,” Burack said. “I was always kind of a shy kid and you know, you have people asking you questions and asking you to do stuff. It was a little bit horrifying.”

“It was weird, and I hated it, you know, when I got older,” Morello said.

For a decade -- and longer, in some cases -- the children and their adoptive families said they were visited by those mysterious researchers.

The entire time, the families said, they were unaware that the child they had adopted was a twin and that they were being studied to test how identical twins would fare growing up in different homes.

Burack said that the researchers were still coming to his house when he was 11 or 12 years old, and that at one point, he said he no longer wanted to participate in their research.

It was in 1998, when he was 35 years old and unaware that he was a twin, that Burack wrote to Louise Wise Services asking for information about his biological parents. He said someone called him from the agency and told him the shocking news.

“She said, ‘You have an identical twin brother,’ and I’m like, ‘Well, thanks for telling me that.’ After, I was shocked, but, you know, just how do I find that person? Because that’s what I wanted to do,” Burack said.

He said Louise Wise Services told him that New York law didn’t allow the agency to reveal the identity of his brother, and so he was left in limbo, unable to locate his sibling.

“I spent about two years, every day, thinking about this. It never left,” Burack said.

He said he started looking at people he encountered in the world for a face that looked like his. He even asked people to tell him if they ever saw someone similar to him.

“It was pretty disturbing. I mean, it was just an unknown. It’s like, ‘How could I find this person? Am I ever going to find this person? Is this person alive?’” he said.

The hunt for their records

Doug Rausch found out about his secret history two years after Burack did. In 2000, Louise Wise Services was in the process of going out of business.

“When Louise Wise was shutting down, there was a woman there who had cancer and who knew she was dying, and before she left, and before this place closed down, she called Doug,” Shinseki said. “She couldn’t go to her grave without letting some of these kids know that they had identical twins.”

“She even told me. She goes, ‘I’m not supposed to do this. I can get in a lot of trouble, but I’m going to do it anyway.’ So I appreciate that,” Doug Rausch said. “She said, ‘Well I have some news for you. You have an identical twin brother.’ And I was like, I literally almost drove off the road. It's not something you ever expect to hear.”

Doug Rausch allowed the adoption agency to give his phone number to his twin and waited to hear from the identical brother he never knew he had. When the call finally came, he learned that his twin was named Howard Burack.

“I finally called him and we talked for a while and it was, you know, like I knew this person my whole life. It was amazing,” Burack said. “I think we may have exchanged pictures and stuff after that and you know, it's just like, man, you just see yourself in a picture. It's, you know, it's pretty strange.”

The twin brothers were finally reunited at an airport in Columbus, Ohio.

“I don’t get nervous really easy or rattled and I still remember sitting on that plane dripping sweat and just being so nervous about, you know, meeting this person that looked like me, that I had no connection with,” Doug Rausch said.

Twin brothers meet for the first time after being separated in infancy

Doug Rausch said he laughed when he saw his brother for the first time.

“It was just the funniest thing I’d ever seen ‘cause it literally was like looking in my reflection, but then the reflection would move and do something I wasn’t doing. ... I don’t know how to describe that and I don’t think most people can relate to it, but it was a very, very weird feeling,” he said.

“I mean, it's just like you're looking at yourself in the mirror and, I think we hit it off, you know, right away and you know, instant connection. I felt like I knew Doug my whole life,” Burack said.

As they compared the lives they led, involuntarily estranged, they noticed patterns.

“We lived parallel lives essentially,” Doug Rausch said.

Doug Rausch and Burack both coach hockey and have children who also play hockey. Doug Rausch’s daughter wears the No. 2 and so does Burack’s son.

The brothers also carry their wallets in their front pockets and married their wives in 1992.

“They’ll probably get mad at me if they hear this but I think they're more similar than me and Howie,” Doug Rausch said of his and Burack’s wives. “They both were runners. They both were successful in their fields and they both are pretty type-A personalities. I don’t know, I think they're similar in a lot of ways. And you can only imagine that’s probably because what we both were attracted to.”

Tracking down a twin she didn’t know she had

When Sharon Morello discovered that she'd been separated from her identical twin and also part of a mysterious study, she became obsessed with finding her sister.

“What would it have been like growing up, you know? Would we have been best friends? Would we have hated each other? Would we have shared everything? So many different things, but we never had that chance,” Morello said.

She said she also wanted to warn her sister that she had just battled breast cancer.

“I needed to make sure she was healthy. So I think that’s part of what drove me, that I needed to let her know,” Morello said.

Morello had just enough information to start her search through birth records at the New York Public Library.

“I figured I had my birth certificate. I knew my number. I knew if I have a twin, it's got to be in the book,” Morello said. “I knew my birth first name and my last initial: Danielle G.”

Looking through the records, Morello discovered that what Shinseki, the filmmaker, had told her was true: She had an identical twin sister.

When Louise Wise Services went out of business in 2004, it turned over its records to the Spence-Chapin adoption agency, so that’s where Morello went next and finally got the agency to pass her contact information to her twin.

“I still can envision the whole thing, that email coming with her name and address. And I’m looking at it, like, ‘No phone number? What do I do?’” Morello said. “Thank God for Facebook.”

Morello found her twin sister and sent her a Facebook message.

“We instantly bonded. I mean, from that first email, just clicked,” Morello said. “I asked her like right in the beginning, ‘Are you afraid of anything?’ You know? Or, ‘What are your fears?’ And again, we both don’t like snakes, spiders and heights. And she wrote back the same thing, and she goes, ‘I’m not kidding.’”

They met in person, discovering that they both have two children and that they both named their youngest child Joshua.

Meanwhile, reunited twins Doug Rausch and Burack moved on to the next step in their journey: demanding answers about why they had been separated and studied. The study was conducted by psychiatrist Dr. Peter Neubauer. Neubauer’s data from the study are being held at Yale University under seal until 2066, and only the Jewish Board of Family and Children Services, Neubauer’s former employer, can allow them to be released before that date.

When Doug Rausch and Burack wrote the Jewish Board a letter in 2011, requesting to see their records, the board told them: “There does not appear to be any indication that the Yale material relates to you and your brother. … Therefore, it is simply not possible to grant you access to the Yale material.”

“They received a letter back stating that they were not in the study … It’s just not true,” filmmaker Shinseki said

How the study came to be

Dr. Viola Bernard, a psychiatrist and consultant to Louise Wise Services, believed adoptive twins would thrive more if they were raised in separate homes and getting more individual attention from their adoptive mothers.

Based on Bernard’s advice, the agency began splitting up sets of twins and triplets and placing each sibling with a different family.

Bernard also enabled Neubauer to begin a long-term study of some of the separated twins to monitor how each would fare in different environments.

According to these families, the adoptive parents were not informed that the child they'd received had a twin or of the true nature of the study.

Dr. Nancy Segal, a child-development expert and the director of the Twins Studies Center at California State University, Fullerton, told Shinseki in her documentary that there is “no basis to ever support that” twins are better off in separate families.

“The Neubauer study was unique in a number of ways,” Segal said in Shinseki’s documentary. “First, it was because twins were purposely being separated. Secondly, you never study people without their full knowledge. … They were misinformed that it was a child-development study and that is hiding basic facts.”

Bernard left her papers to Columbia University, with instructions that they were to be sealed until the year 2021.

Confronting one of the study researchers

As Shinseki continued her research, she came across journalist Lawrence Wright, who interviewed Neubauer and Bernard in 1997. His interviews are the only known recordings of the two psychiatrists discussing separating multiples and the controversial study.

In one recording of the interview, Wright asks Neubauer to explain the scope of the study, and Neubauer says: “For special reasons, which if I were to go into it, you wouldn’t understand, the study was only based on a small number of identical twins separated at birth.”

Wright told Shinseki during an interview for her documentary that, “I don't think he ever really acknowledged the damage that they might have done to the twins themselves and the trauma that they were preparing these children to have when they grew into adulthood and one day discovered that they were twins and that they had been deprived of that relationship their entire lives, by scientists who wanted to study them.”

According to Wright, Neubauer wouldn’t give any specifics about the study because it hadn’t been published. It turns out the study was never published.

Before Neubauer died, Doug Rausch said he got the chance to talk with him on the phone.

“That didn’t go too well,” Doug Rausch said. “And I asked him straight, I go… ‘Why would you do something like that?’ And he thought it was fine. … He wanted me to come down to New York so he could interview me. … The conversation didn’t end well, let's put it that way.”

Doug Rausch said he felt like he and others had been treated like “lab rats.”

“That just blew my mind that he thought, at 90 years old, thought that was fine,” he said.

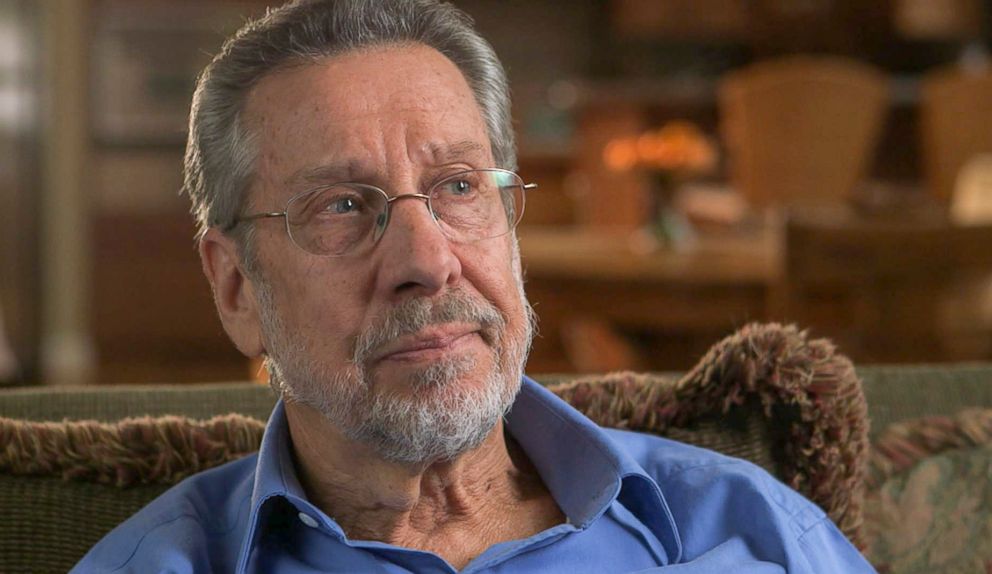

Shinseki, the filmmaker, was able to find that some of the people who actually visited the children at home, collecting data for the study, were still alive. Larry Perlman, a research assistant on the study, took the job as a young graduate student.

He is featured in Shinseki’s documentary and told her that his job was mainly to help with the organization’s analysis of the data.

“We wanted to see if we could tease out some of the subtleties of his [Neubauer’s] child-rearing processes and family dynamics and how that might affect the development of these two individuals who were genetically identical, but are being raised in totally different families,” Perlman said.

After interviewing Perlman, Shinseki told Doug Rausch and Burack that Perlman said he had studied them in their separate, adoptive homes when they were 6 years old.

The brothers then met Perlman, who said that at the time he became involved in the study there were five sets of twins being monitored.

“The way the study was set up was during the first year of life,” Perlman told them, “I think, they had visits four times a year. Then it went down to twice a year, then once a year. So they had all this material that they didn't really know how to analyze. It wasn't a sophisticated research operation by any means. In fact, they didn't really know what they were doing from a research standpoint, but they had this terrific source of data because they had these twins who were being separated.”

Shinseki tracked down another researcher named Janet David, who said she'd made a few house calls to study the separated twins, including Morello.

During one home visit, David said she realized that she'd gone to college with Morello’s adoptive mother, but even then, she said, she didn’t reveal the true intention of the study or that Morello had a twin.

Recently, David agreed to meet with Morello, her mother and ABC News consultant Pam Slaton, an investigative genealogist.

Former researcher questioned about secret study with separated identical siblings

Morello asked David why she'd never mentioned to her or her mother that she had a twin, but David said she left the study shortly after meeting Morello.

“So I had nothing to do with anything like that. … I had nothing to do with policy to begin with,” David told them. “I was low on the totem pole. I was just barely starting graduate school. I was really working as an administrative assistant, and then I got called in to do a couple of home studies like yours and, and a couple of others. So I had no authority, no clout, no nothing.”

David said that she'd been told that the families didn’t know their adoptive child had a twin, but she didn’t feel that the way the study was handled was wrong.

“We knew that the families were competent parents and so. … There’s no, no harm here,” David said. “That part never struck me as wrong. It looked like the babies are going to good families.”

“I mean, I’m sorry. I’m sorry about it,” she said. “But, I was not responsible.”

Both Morello and her mother said they were disappointed by what they'd heard from David.

“It didn’t occur to her that what she was doing was screwing with people’s lives,” Bregman said.

Finding some answers about their past

Doug Rausch and Burack were able to get some answers, with the help of an attorney with whom Shinseki put them in touch with.

Because Perlman kept his notes of home visits with the two brothers, proving they were part of the study, in 2013, the twins were able to get the Jewish Board to release some of their records.

Although Bernard, the psychiatrist, had told Wright in 1997 that she only favored separating twins shortly after birth so they wouldn’t develop an attachment for each other, Doug Rausch and Burack said that after reviewing their records, they could see she didn’t follow that rule wasn’t followed with them.

According to the brothers, they were together until they were 6 months old and then they were separated and adopted by different families. They said the records also showed that after they were separated, the two infants showed signs of stress and a decline in motor dexterity. The records also said both began rocking after adoption, with one of them exhibiting headbanging until his second birthday.

“To do what they decided to do, even against their own stated [policies,] they did it anyway,” Doug Rausch said. “It's just wrong. What they did was really, really wrong. The more stuff I read, the more wrong it seems and the more upsetting it gets.”

Morello and her twin sister were 3 months old before they were separated. When the two did reconnect, Morello said her sister told her that she always “felt alone and that something was missing.”

But Morello said she and her sister are no longer on speaking terms since she has gone public with their story.

However, Slaton, the investigative genealogist, was able to track down Morello’s birth mother and connect them. Her birth mother said she had never forgotten about her twin girls and thought they would be adopted together.

“And then when she called [the adoption agency] back to say, ‘Did you find a home for them?’ She was told, ‘Yeah, we found homes for them. They're being split,’” Morello said. “She was heartbroken. Absolutely heartbroken.”

Morello and her birth mother have not met in person yet, but they have exchanged several messages.

“I’m so grateful for what she did, you know, gave birth to us and so sad for what she went through,” Morello said. “It's horrible what she went through, giving us up, and it's not what she wanted.”

The children in the study

Of the at least 15 children believed to have been separated from twins or triplets by Louise Wise Services, some have reported serious mental health issues, according to Shinseki.

She said it appears that at least three separated siblings committed suicide, including Eddy Galland, a triplet who took his own life in 1995, 15 years after reuniting with his brothers.

“His wife says that he was never able to get over the separation and the loss. … Nineteen years that he didn't have with his brothers,” Shinseki said.

For the twins Shinseki spoke to, she said, the pain of being separated has been very real.

“It’s their belief that it, at least, had some impact. The separations had some impact on their feelings of sadness and loneliness and depression as children,” she said, “so I can’t know that, but they believe it.”

There may be other children, now adults, who have no idea they were separated from their identical siblings or part of this study.

“20/20” made repeated attempts to contact Spence-Chapin -- now the repository of all of the Louise Wise Services adoption records, including the names of the twins who were separated -- but thus far, has not received a response.

And as for Neubauer’s study data currently at Yale, only the Jewish Board has the authority to release it.

Last summer, Morello, Doug Rausch, Burack and their families attended a screening of Shinseki’s documentary, “The Twinning Reaction,” at the Jersey Shore Film Festival.

The movie won the best documentary award. Shinseki hopes it will serve as a cautionary tale.

“Humans are not data,” she said. “And I think that is a big danger as we get into genetic testing and experimentation that people in power have to be very careful to remember that you can really affect someone’s life, in ways that you just didn’t even mean to.”

Doug Rausch and his twin brother, Burack, are not angry or bitter, according to Burack.

“It would have been awesome growing up together, but I believe we were both very lucky and are not looking backward,” he said.

They’ve decided to share their story, so that other twins who may have been split up can find each other and to make sure something like this never happens again.

Resources:

If you were adopted through Louise Wise Services and interested in receiving information from an adoption record, you can contact Spence-Chapin Services to Families and Children. Spence-Chapin, as an authorized agency, is the custodian of all Louise Wise adoption records.

Spence-Chapin Services to Families and Children pah.info@spence-chapin.org Request Records Line: (212) 788-3207 If you think you may have been in the study by Dr. Neubauer, you can contact the Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services: Jewish Board of Family and Children’s Services 135 West 50th St, New York, NY 10020 Phone: 212.582.9100 Toll-free: 888.523.2769