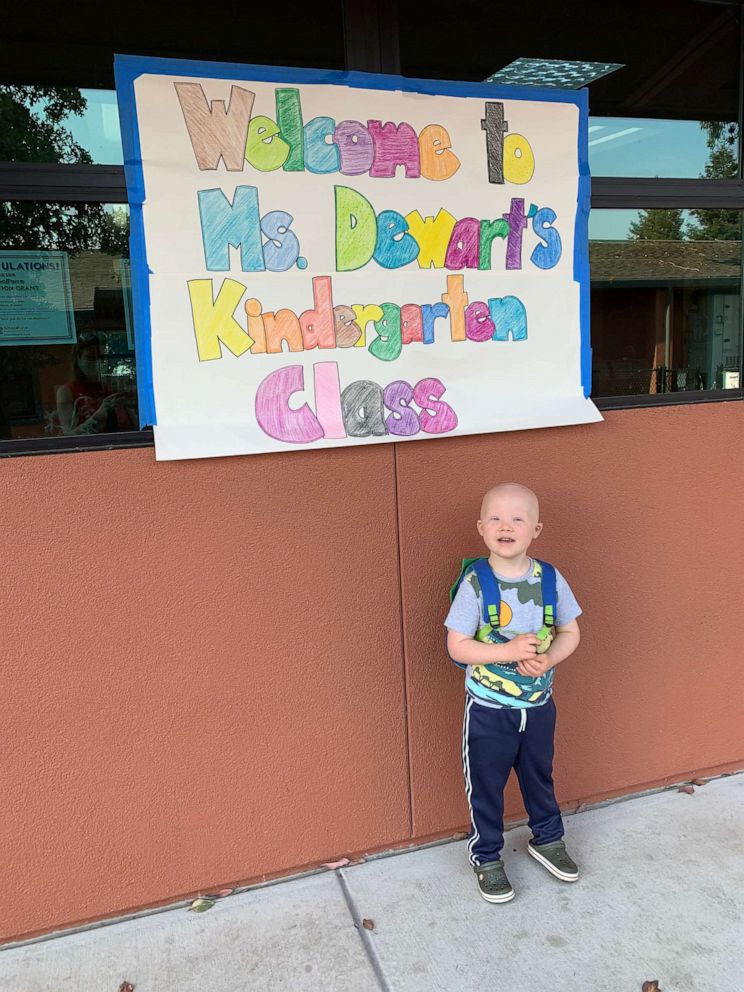

On Monday this week, I dressed up my 5-year-old boy, all bright eyes and smiles and backpack-sporting glee, for his first day of kindergarten. We gathered in our ritual spot on our porch to take first-day-of-school pics. We yelled "CHEESE" and "GO PUMAS!" to capture his maturing little face in a delightful smile. And then we walked back into the house to start school on Zoom.

I was a ball of nerves, for many of the reasons every kindergarten parent is frazzled right now.

It's distance learning.

With 25 five-year-olds.

While we're all working full time.

(Need I say more?)

But I had an extra excuse for my high anxiety and deer-in-a-headlights gaze: My son has Down syndrome, a naturally occurring chromosomal condition that comes with some intellectual and physical delays. He also has alopecia, a fancy word for hair loss, meaning he's bald as a cue-ball. That's something other kids notice, big-time. In a word, he's different. And he was starting kindergarten as a member of an inclusive class. As far as I know, he's the only one of his classmates who is classified as having "special needs." He's not pulled out into a separate special education setting. He's there with his typically abled peers, where he rightly belongs.

Since 1975, when federal law changed to require public schools to provide a free, appropriate education to all children regardless of their ability, parents of differently abled children have fought for them to be included with their peers. Decades of research has shown that combining children of all abilities in a classroom yields better academic and social results for all stakeholders. Pockets of our public education system have caught on, but only after long and hard work to change hearts and minds.

Parents of differently abled kids are no different from any other parents in this fundamental way: We want our children to be accepted by the world. We want them to be seen, embraced, befriended, included, and loved. We want them to have opportunities. But when your child is noticeably different, you just can't take that condition for granted. So we worry and we advocate and we bravely build bridges with our communities and the school system. We bear the heaviness of this work. We hope it's enough.

Now and then, we get a reminder that it is enough. And it washes all that anxiety away and recharges our courage batteries.

On Friday last week, we went to my son's new school to meet his teacher and pick up supplies. There, at the front entrance of his school, I saw this gorgeous, slightly weathered, hand-painted sign. "Welcome," it read, "All abilities. All religions. All orientation. All cultures. All colors. Love lives here."

It was just some words painted on a sign. "Welcome ... All abilities." And it was everything.

My son's public school is renown in our city for its emphasis on inclusiveness. The parent community attributes this to the philosophy of the longtime principal at the school, who chose inclusivity as a core value. But she left the school at the end of this year, and already, I can see that her impact lives on. Inclusivity seems to be woven into the school's DNA.

At a "welcome to kindergarten" meeting, the special education program coordinator informed us that the district's default placement for kids with special needs is in a general education setting, not a separate classroom. My son's kindergarten teacher was enthusiastic to have him included in her class. She told me she's eager to learn from me how she can make the year successful for him. The school has fantastic support in place and has been terrifically communicative with us about how we'll make the curriculum work for him. The other kids have been kind, curious, and welcoming. So have their parents.

We're lucky. It won't be like this for so many of the other 7 million students who are differently abled in this country. That's 14% of all students in public education nationwide. So many of them will be dismissed. Set aside into separate rooms. Treated as a burden, rather than a treasure. We have so much work left to do.

When I saw this sign at our school's front door, my spine grew an inch taller, and I said a silent prayer of thanks for all the parents who have come before us to fight for our children to be included with their typical peers. And then I pinned a picture of it to my bulletin board, as a reminder to be grateful, to hoist up my advocacy load and to continue the work.