This woman lost her memory during childbirth. Her husband wrote a book of their love story to help her remember.

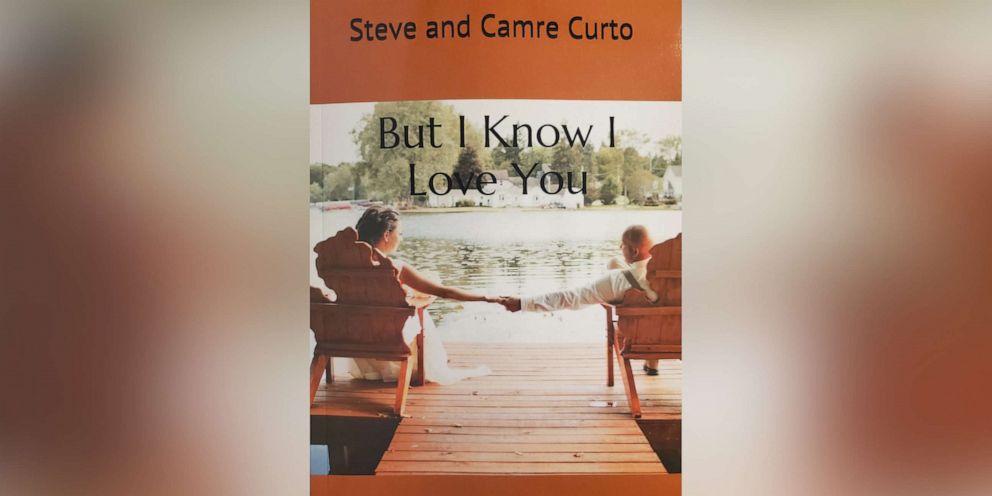

"But I Know I Love You" documents the lives of Steve and Camre Curto.

Steve Curto wanted a way for his wife, Camre, to remember their 10-year relationship, everything from their first date to their wedding and the birth of their son.

So Curto, 38, of Michigan, wrote a book, "But I Know I Love You," that he self-published and released on their fourth wedding anniversary last month.

Camre Curto, 31, has no memory of anything her husband documented in the book.

She lost both her long-term and short-term memories when she suffered a stroke and a seizure on the day she gave birth to the couple's 7-year-old son Gavin.

"Everything in the book is a memory of what we've gone through and what I've missed," Camre Curto told "Good Morning America." "I enjoy [reading] it very much, but right now with everything it’s kind of mixed feelings."

"Sometimes it’s hard for me because it shows me everything that we have been through and that I don’t have inside of me," she said.

Camre had a normal, healthy pregnancy up until her third trimester, when she started to experience frequent vomiting, according to Steve.

One day 33 weeks into her pregnancy, Camre's throat began to swell and she had trouble breathing. Steve rushed her to the emergency room, where she went into a grand mal seizure.

Doctors quickly performed an emergency c-section on Camre and delivered Gavin, who weighed just over four pounds, according to Steve.

In addition to the seizure, Camre also suffered a stroke that affected both sides of her brain and wiped out her long and short-term memory, according to Camre's occupational therapist, Jessica Smith.

"She couldn’t recall memories prior to her brain injury and she can’t remember short-term memories now," said Smith, a therapist at Galaxy Brain and Therapy Center in Ann Arbor, Michigan. "What happened to her is extremely rare."

Doctors later determined that Camre had undiagnosed preeclampsia, a pregnancy-related high blood pressure disorder which reduces blood supply to the fetus, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

She then went into eclampsia, which is when pregnant women with preeclampsia develop seizures or coma. Camre was intubated and put into a medically-induced coma, so doctors and her family did not immediately know the extent of her memory loss, according to Steve.

"When they brought her out of the coma, and she started to wake up, something wasn’t right," he said. "She had no idea who she was or that she had just given birth. She didn’t know who I was or who her parents were."

Camre spent 30 days in the hospital after giving birth, while her son Gavin spent 36 days in the NICU after his premature birth.

"I basically lived at the hospital," said Steve. "They want the child to bond with the mom after birth but Camre wasn’t able to bet there, so I did skin-to-skin with him and did all the feedings."

When Camre was released from the hospital, a few days before her son, it was like she was a newborn child too, according to Steve.

"She would say, 'Where are we?,' and I would tell her we're in the hospital to see Gavin and she would say, 'Who's Gavin?,'" Steve recalled. "You just have hope that it’s going to be okay. That was my mindset."

Camre spent the first months of her recovery living at her parents' home and visiting Steve and Gavin at the family's home, where Steve was essentially raising Gavin as a single parent.

Camre was fine physically but didn't remember the daily tasks of life, like getting dressed for the day and brushing one's teeth.

She also didn't remember Steve and didn't remember the home they lived in before her brain injury, he recalled. It was one conversation they had while sitting in her parents' home that motivated Steve to continue to put all his effort into helping Camre recover.

"We were sitting on the couch and she told me, ‘I don’t who you are but I know I love you,'" said Steve, who used those last five words as his book's title. "That has always stuck with me. That has been the driving force behind everything."

"When I met Camre, she made me want to be a better person and that’s what I loved about her," he said. "Then this happened and I just wasn’t going to give up hope that we could regain what we had. This girl, she has no idea who I am but she loves me and we’re going to make this work."

Camre began working with Smith, the occupational therapist, five years ago. With her support, and with Steve at nearly every appointment, Camre has re-learned everything from how to cook to how to change a diaper to how to get herself dressed.

"When I first met her she was there, but not really there. She was a shell," Smith said. "Now she’s got her personality back and she’s able to be a mom to Gavin, which is the best thing to see."

Camre has developed her own memory tricks too, like writing things down and doing things over and over to put them into her rote memory. She and Steve have a joint calendar they share on their phones so she knows the family's schedule.

Camre also now knows and remembers Steve and Gavin, and credits them with keeping her going.

"With my husband and son with me, that is what is getting me through all this," she said. "Every time I see Gave and Steve, there’s a huge smile on my face and inside me. The love of family is what means the most and what is getting me through every day."

Camre has developed a "fantastic" mom-son relationship with Gavin, who understands what happened and that his mom "doesn't have a memory like other people," noted Steve.

"There are little things in life that I’m beside myself that she can do, like going to a mother and son flag football game," he said. "The little things are adding up and to me and to her too, the little things are huge."

One painful bump in the family's journey came about two years after Camre's brain injury, the point at which she realized she had lost her memory.

"She started to realize that she couldn’t remember and that made it more difficult because she knew what’d she lost," he said. "Memories are everything to us and most people take them for granted, I know I did. That’s one reason I’m sharing the story."

Another complication in Camre's recovery is that since the brain injury, she has had epilepsy and suffers from frequent seizures. She is on multiple medications to help control her seizures, but those medications may also affect her memory, so it's hard to tell how much memory she has actually recovered, according to Smith.

At this point in her recovery, a focus of Camre's therapy with Smith is helping her regain her confidence.

"When you first meet her and you’re talking with her, she’s really funny and good at playing it off and you don’t know initially that she’s had this significant diagnosis," said Smith. "One of the things that she always tells me that it’s extremely difficult to not remember your son’s first steps or the first time he said, ‘Momma,' because that’s really what moms talk about some times."

"So we role play conversations and do them over and over," she said.

Camre has found a favorite song -- "Everything's Gonna Be Alright" by Kenny Chesney -- that she listens to multiple times per day.

She said she has adopted the song's lyrics as her motto to get her through what she calls a "very difficult time."

"No matter how hard things are or have been and can be, you just have to give yourself hope and keep going, taking each day at a time," she said. "I just tell myself everything is going to be okay and I move toward that."