'Rosie the Riveters' awarded Congressional Gold Medal years after World War II

The women of World War II were awarded with Congress' highest civilian honor.

The women who became known as "Rosie the Riveters" for their work in helping to lead the United States to victory during World War II were honored Wednesday with a Congressional Gold Medal.

"These are the women who built our bombs," House Speaker Mike Johnson said Wednesday at the medal ceremony, held at the U.S. Capitol. "These are the invisible warriors on the home front."

"Rosie the Riveter" was the moniker given to women who went to work during World War II, taking on roles historically dominated by men while men were drafted to fight overseas.

Around 5 million civilian women went to work during the war, many helping to build equipment for the war, while around 350,000 American women served in the military, according to the U.S. Department of Defense.

Decades after their work, the "Rosie the Riveters" were collectively awarded Wednesday with Congress's highest civilian honor.

"This recognition is long overdue, but today Congress finally bestows this honor on these deserving patriots," said Republican Sen. Susan Collins, of Maine, a cosponsor of The Rosie the Riveter Congressional Gold Medal Act, legislation that was passed in 2020 and led to the women receiving the medal Wednesday.

One of the dozens of original "Rosie the Riveters" who traveled to Washington, D.C., to receive the medal in person was Lucille "Cille" MacDonald, a 98-year-old who lives in Hawaii.

When the war broke out, MacDonald, then a 17-year-old, left her family's farm in South Carolina and hopped on a Greyhound bus to Georgia to help.

MacDonald told ABC News that she was "scared to death" when Japan dropped a bomb on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

"That's when I said, 'Do something about it. Just do something about it. Stop worrying and do something about it,'" MacDonald recalled. "So I became very patriotic and very much in love with my country."

MacDonald became a journeyman welder in Brunswick, Georgia.

"I was the best welder in the entire shipyard," she recalled. "I can't forget that. I can't ever forget that. The best, and boy that's saying a lot. And I launched one huge ship a week. In just a week. I mean, imagine. You know how big a ship is? A ship is huge."

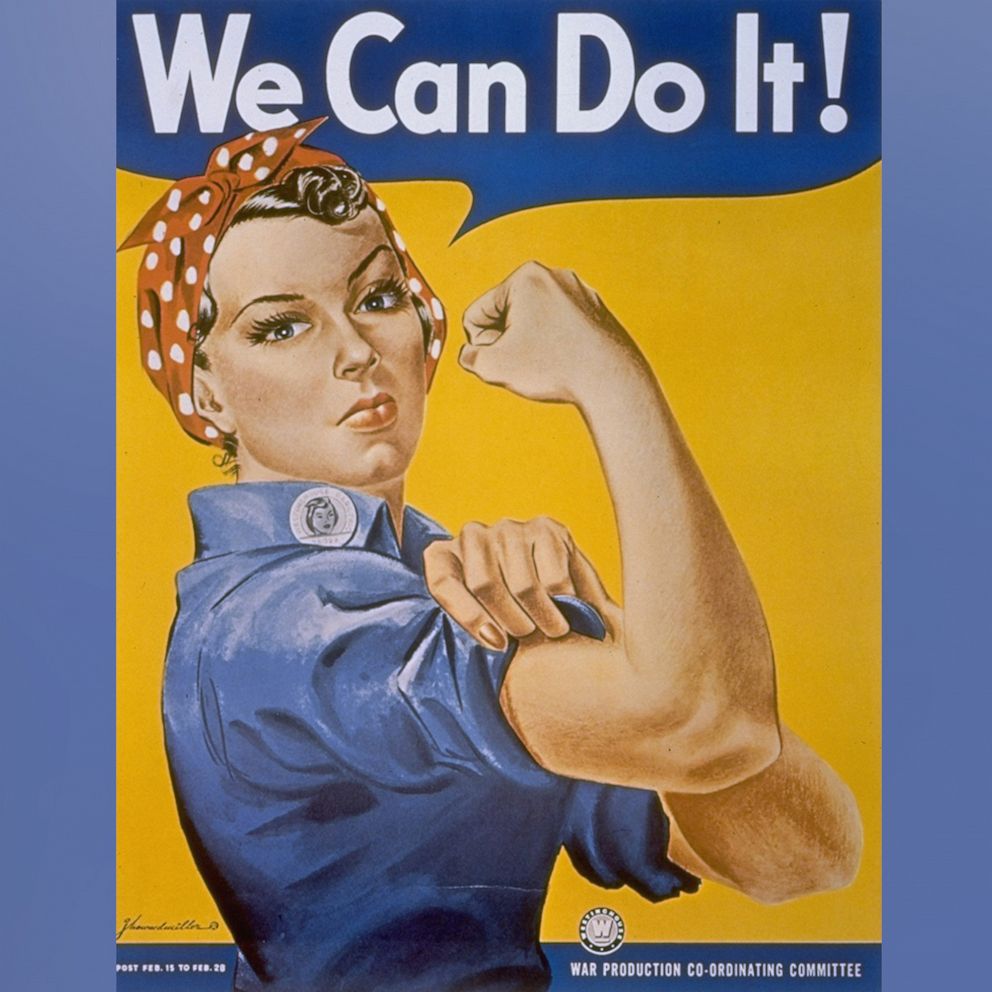

Another woman honored Wednesday was Mae Krier, a Levittown, Pennsylvania, resident who built B-17 and B-29 bombers in Seattle from 1943 to 1945. Years later, at the start of the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, Krier, 94 years old at the time, began making face masks in the same red polka dot fabric worn in the famed "Rosie the Riveter" poster.

She was credited Wednesday for being an "unrelenting advocate" in making sure the women of her generation received their due.

Krier, dressed in a red polka dot vest, accepted the Congressional Gold Medal on behalf of all the Rosies, calling it a "great honor."

"Up until 1941, it was a man's world. They didn't know how capable us women were, did they," Krier said to loud applause, later adding that she is most proud of the path she and other women set for future generations.

"We're so proud of the women and young girls who are following in our lead," she said. "I think that's one of the greatest things we left behind is what we've done for women."

Krier ended her remarks with the words that came to symbolize the motto of "Rosie the Riveters," saying, "We can do it."

ABC News' Stephanie Wash, Jaclyn Lee, Derick Yanehiro and Meredith Deliso contributed to this report.