Amid darkest days of coronavirus pandemic, unprecedented vaccine effort enters final stage

As the virus ravaged the globe, researchers fought back with science, ingenuity.

The post hit the internet on Jan. 10. Uploaded to an obscure medical website, it was met with little fanfare. But to the world’s scientific community, it was like a gunshot at the starting line.

The race was on.

For weeks, newscasts had featured increasingly frightening scenes from Wuhan, the central Chinese hub where a mysterious contagion was rapidly spreading.

But just days into the New Year, researchers in China had finally revealed the genetic code of the novel coronavirus, offering Western researchers their first glimpse into the pathogen's potency – and its simplicity.

Almost immediately, on the other side of the world, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the top infectious disease expert in the U.S., scrambled to mobilize his team of researchers at the National Institutes of Health. He tasked Dr. Barney Graham and Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett to lead the fledgling search for a vaccine.

“As soon as the sequence went up, the scientists from the Vaccine Research Center said, that's all we need,” Fauci told ABC News. “The next day we had a meeting and said, ‘let's go for it. Let's make the vaccine.’”

As Graham and Corbett examined the genetic sequence, it became clear that recent leaps in their vaccine development research might prove to be useful in finding an eventual inoculation against this novel -- and deadly -- coronavirus.

Nearly a year later, as healthcare providers begin dispatching a newly authorized vaccine, Fauci credits these early steps with what he characterized as the “unqualified success” of the vaccine development program.

“It really is a reflection of years of fundamental, basic, and applied science, which led to technical logical advances that have allowed us to do in weeks to months, what would have taken literally several years,” Fauci said. “To go from the identification of a perfectly new and previously unidentified virus in January of 2020, and have vaccine ready to administer to people in December of that same year, is unimaginable,” Fauci added. Indeed the previous record for vaccine development was four years.

The unprecedented and ongoing vaccination program is the subject of an ABC News “20/20” primetime documentary called “The Shot: Race for the Vaccine,” featuring exclusive access to the vaccine’s low-temperature storage facilities and interviews with Fauci, Graham, Corbett and other core leaders responsible for the historic effort.

'Monumental' public health feat amid genetic revolution

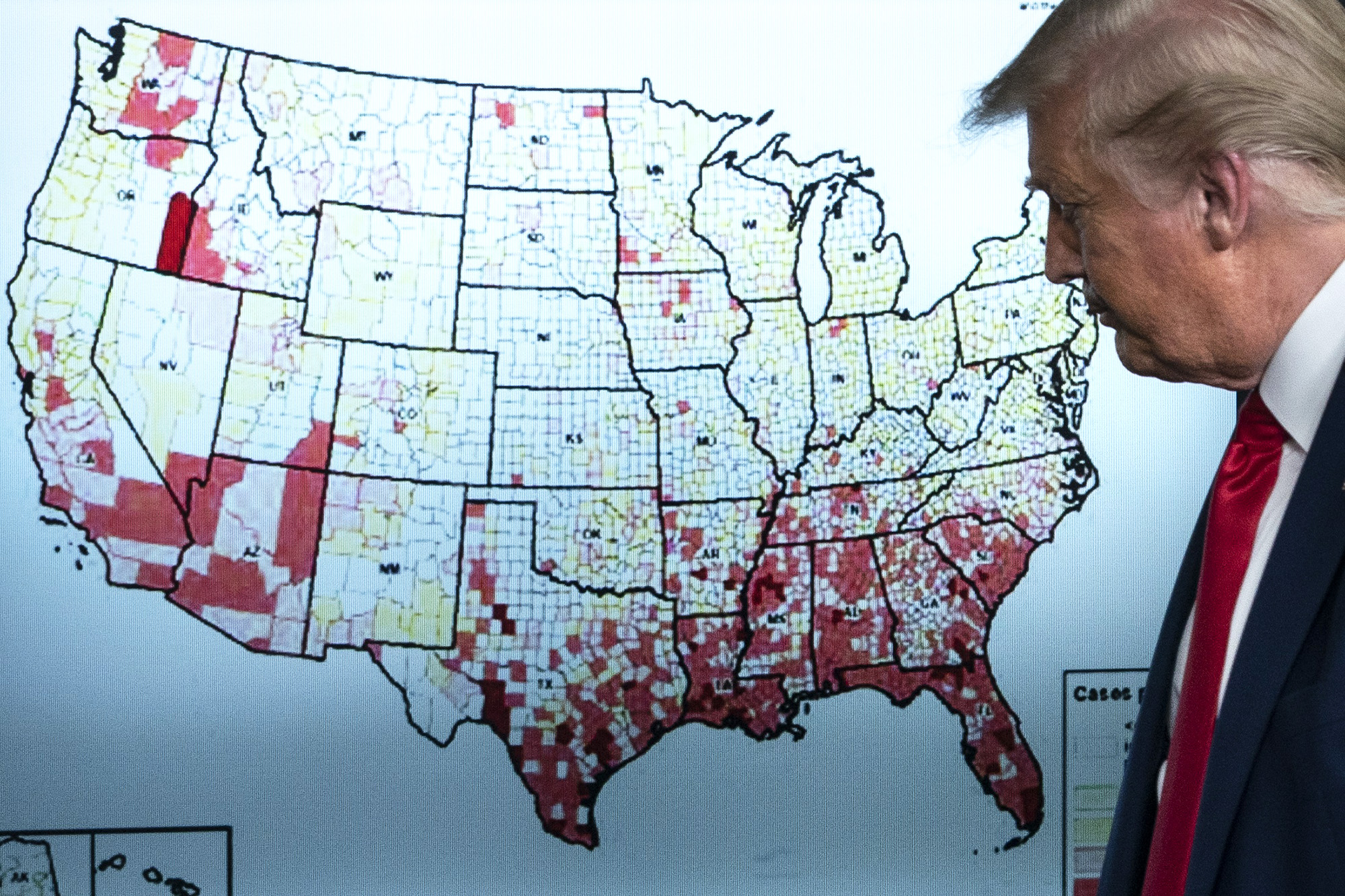

In the past year, Americans have lost lives, livelihoods, and all semblance of normalcy. The coronavirus is already responsible for more than 1.6 million deaths worldwide and nearly 300,000 deaths in the United States alone. As of Sunday, the U.S. has recorded over 16 million positive cases – and experts are warning of an even deadlier winter ahead.

But as the virus has ravaged the globe, the world’s researchers have fought back with the only tools at their disposal: science and ingenuity. The result of their tireless work appears to be finally coming to light, perhaps marking the beginning of the end of the deadly scourge.

Unlike pandemics of centuries past, COVID-19 has coincided with one of medicine's major revolutions – genetic technology – which has allowed scientists working on the vaccine to move at an unprecedented pace.

“If we're able to pull this off, it will be one of the most monumental public health achievements of our lives,” said Dr. Richard Besser, CEO of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a former acting director of the CDC, and ABC News’ former chief health and medical editor. “I have never been more hopeful during this pandemic than I am right now, and the reason for that is that I know the power of vaccines.”

These leaders in government, science, and industry have collaborated to place the world on the cusp of turning the tide against the virus in a once-unthinkable time frame – and not just a marginal victory, but something that could well be a silver bullet meant to stop this viral predator in its tracks.

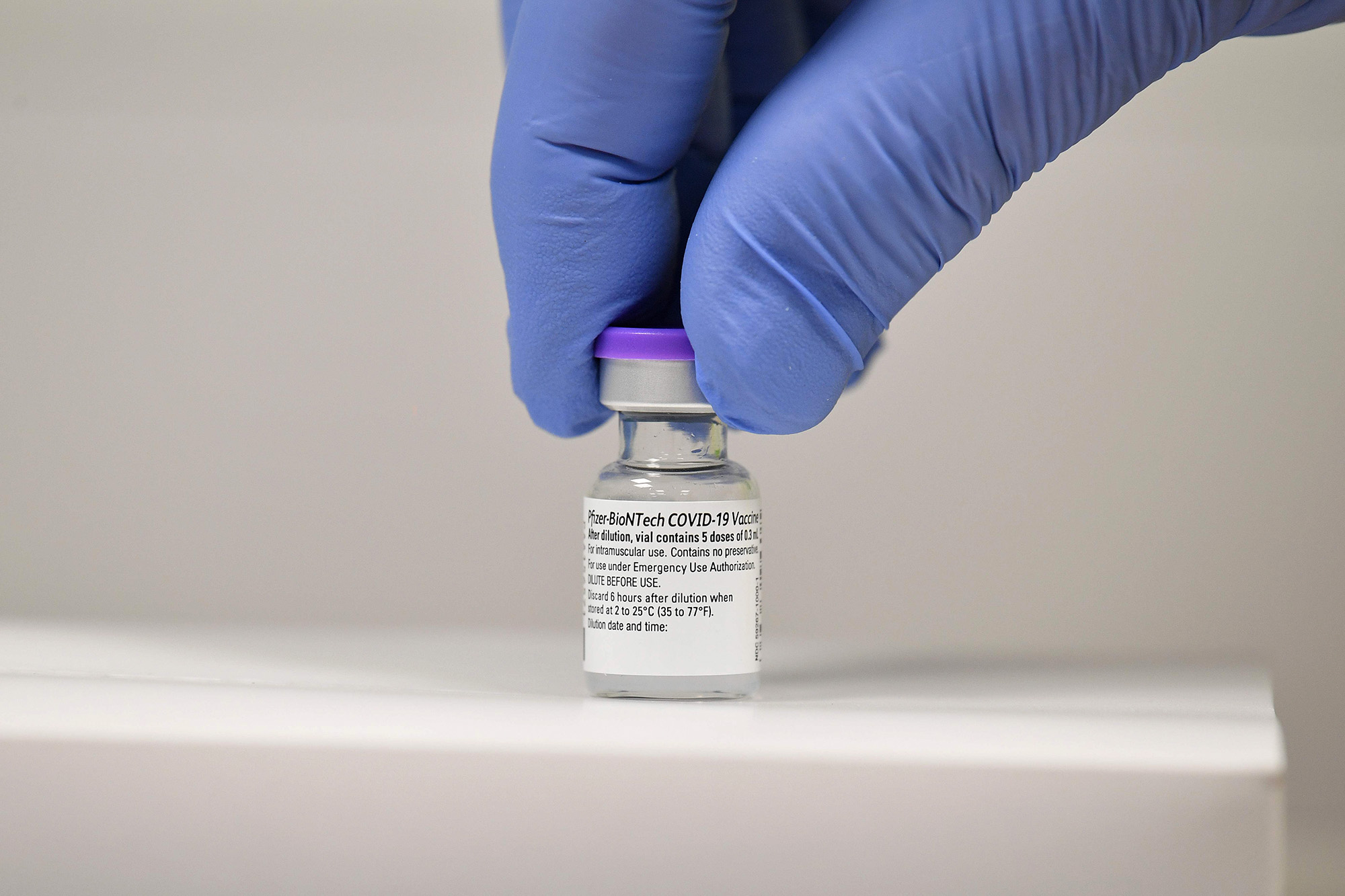

Healthcare providers are now poised to begin vaccinating Americans after the Food and Drug Administration last week granted emergency authorization for the vaccine from Pfizer and BioNTech. Final authorization will require months more study.

“This is a year when we've seen a miraculous scientific achievement,” said Dr. Paul Offit, a vaccine expert at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and a member of the independent panel examining the scientific data and advising the FDA on whether the COVID vaccines are safe and effective.

“It is really remarkable,” Offit continued. “There is really nothing to compare it to. That you can make a vaccine that quickly, that efficiently and that well – it's without historical precedence.”

A rush of experimentation in the private sector

As NIH researchers began their work in mid-January, some of the biggest private-sector brands mobilized, too. Within months, more than 130 vaccines were being studied, according to the World Health Organization – including two promising candidates made by Pfizer and Moderna, the first to seek emergency authorization from the FDA.

The insights first gleaned in the NIH laboratories by Graham and Corbett were passed on to the biotech company Moderna, which in March became the first to launch a clinical study in humans in the United States, with Pfizer and others soon following.

From major pharmaceutical firms to logistics, airlines, and tech, a whole-of-industry effort quickly got underway.

“I got a call from my boss, who runs the entire supply chain of Johnson & Johnson, and she said, ‘Hey, we need to develop a vaccine, we need to supply a billion doses, I need you to get on that,’” said Remo Colarusso, a vice president at Johnson & Johnson responsible for global manufacturing and supply chain management. “I'll never forget getting that call.”

Meanwhile, as the vaccine effort progressed into the spring, the nation was forced to shift gears. Hospitalizations and deaths skyrocketed and cities and states began to grapple with stay-at-home orders.

“The fear around this virus really hit home for me in March, when it was super clear that we were dealing with a pandemic that we have not experienced in the history of this nation,” said John Brownstein, PhD, an epidemiologist with Boston Children’s Hospital and an ABC News contributor.

“But at the same time,” Brownstein added, “we're dealing with a government response that was far from what one would expect and need to get this virus under control.”

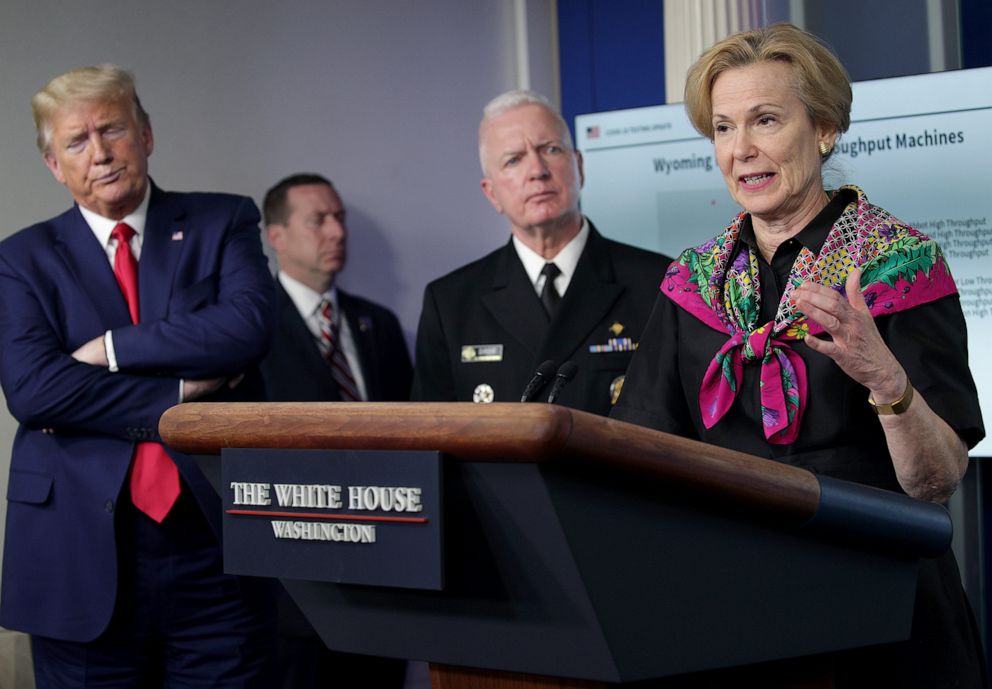

President Trump’s incessant downplaying of both the virus and his refusal to accept common-sense measures meant to curb its spread – like wearing masks – made it difficult for top scientists in his administration to convey a unified message to the American people.

But even as Trump and his allies cast doubt on much of the science, administration leaders insisted their faith in a vaccine never wavered.

Operation Warp Speed

Even while downplaying the virus and mitigation measures in favor of economic recovery, Trump publicly promoted an aggressive timeline to develop and distribute a silver-bullet vaccine.

“The president and I were looking at the timelines that the drug companies were saying … and the president and I said, ‘that's just not acceptable,’” U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar told ABC News, reflecting on the early days of the pandemic. “We can get a vaccine by within months, not years.”

To meet that ambitious goal, the Trump administration launched Operation Warp Speed, a multi-billion dollar effort to develop and distribute a vaccine in record time, without skimping on safety measures.

The “Warp Speed” branding traces back nearly 60 years to the original "Star Trek" television series, which followed the journeys of a galaxy-hopping spaceship from the Earth of the future. The government’s plan was to take on all financial risk, meaning taxpayers would fund the production of hundreds of millions of doses of a vaccine as the new drugs went through rigorous clinical trials (although Pfizer, for instance, did not accept government funding for development – but agreed to sell 100 million doses to the U.S. upon completion for a whopping $1.95 billion).

It was a massive bet with even bigger implications: the future of the world might depend on its success. Officials and experts maintain that no corners were cut, insisting that the crash pace of development came as a result of taking multiple steps simultaneously, rather than doing them one after the other, as is typical.

“It's not only not the normal timeline for a vaccine to be developed in months, it's unprecedented. It's historic,” said Dr. Jen Ashton, ABC News’ chief health and medical correspondent. “The average vaccine takes decades to develop.”

In light of Trump’s public pressure campaign for a speedy vaccine – and an election season looming in the not-so-distant future – concern quickly developed that the administration might fast-track a vaccine in a way that threatened public safety. The president had also taken to promoting unproven therapeutics, like hydroxychloroquine, emergency approval for which was eventually revoked.

“I was really worried about how much this vaccine was going to be politicized,” Offit said, adding that he feared the Trump administration “would just dip their hand into Operation Warp Speed, compelled by the fact that there was an election that was coming up, and say, ‘here, here is my gift to the American public.’”

The name itself garnered scrutiny, too. Many Americans interpreted “Operation Warp Speed” as yet another cartoonish utterance from a White House bereft of the seriousness of a crisis that was killing Americans across every region, age-range, and socio-economic group.

Others worried the Warp Speed branding could undermine confidence in the vaccine product.

“The first thing I thought was, I wish somebody had come up with a different name,” Offit said, fearing the name might give the impression that vaccine developers would risk “ignoring safety guidelines” in the name of expediency.

Even so, Operation Warp Speed plowed ahead, making inroads and investments with private sector pharmaceutical companies and plotting the largest vaccination program in history – a logistical feat the likes of which had never been attempted.

“We started building the airplane in flight,” said Gen. Gustave Perna, a former leader of the U.S. Army Materiel Command who was named chief operating officer of Operation Warp Speed.

“I've got three problems to solve,” Perna explained. “I need to solve development: how do we get a vaccine, shown to be safe and effective, as quickly as possible, through the FDA process? Two, how do we manufacture a protein? And third, distribution and logistics.”

Facing skepticism

As Operation Warp Speed laid the groundwork for the massive vaccination program, multiple vaccine candidates sailed through the early safety trials and advanced to phase 3 -- large-scale human trials to determine efficacy. In desperate need of tens of thousands of volunteers to participate in the final studies, it fell to everyday Americans to step up.

“I said, ‘I want to join,’” said Dan Stepenosky, a high school teacher who volunteered for the Pfizer vaccine trial. “I really expected they would say no. I'm a cancer survivor … but I wanted to throw my hat in the ring anyway, and after going through the screening process, they allowed me in.”

“Someone's got to do this,” Stepenosky added.

Not everyone shared Stepenosky’s faith in science. Over the summer, polling began to show widespread mistrust in vaccinations amongst Americans – especially in groups at higher risk of becoming sick from COVID-19, like African-Americans and Latinos – a potential threat to the viability of a vaccination program.

The anti-vax movement, as it’s known, remains a small but vocal advocacy niche that has re-emerged in recent years within a burgeoning social media disinformation ecosystem.

On top of that, a broader vaccine skepticism -- fueled in part by the politics of the moment and the litany of inaccurate statements emanating from the White House and other leaders – developed both before and during the onset of the pandemic. Among African Americans, for example, a history of being improperly exploited in scientific experiments has fueled skepticism.

And as the president’s rhetoric continued to conflict with the advice of his top scientists, Sen. Kamala Harris declared at the vice presidential debate that “if Donald Trump tells us” to take the vaccine, “I’m not taking it” -- but said she would be “first in line” if Fauci signs off.

“There's a lot of data about how reluctant will people be to take the vaccine,” philanthropist and Microsoft founder Bill Gates told ABC News. “You know, we're going to have to have voices who are trusted speak out about this and continue to be open about the data.”

Efforts to convince Americans of the vaccine’s safety appear to be paying off. A new ABC News/Ipsos poll released Monday found that more than eight in 10 Americans now say they will receive the vaccine.

A safety guardrail and a breakthrough

One way federal regulators sought to ensure safety was by instituting rigorous safety trial standards, most notably a rule set out in October stipulating a mandatory safety guardrail before the FDA would consider authorizing any product, according to FDA Commissioner Dr. Stephen Hahn. The FDA’s regulation was designed to ensure that no vaccine candidate could seek authorization without a full two months of data in at least half the volunteers from the ongoing human trials.

The move pushed back the vaccine timeline, which infuriated the White House, but ensured that a vaccine could not be used as a prop in the presidential election on or before Nov. 3.

“What we've insisted upon at the FDA if a vaccine is authorized,” Hahn said, “we will insist upon a very vigorous follow up program to collect data on side effects.”

For some experts who had previously expressed concern that political considerations may seep into the approval process, Hahn’s 60-day rule represented a major turning point.

“When [Hahn] stood up for the American public there, I think we all breathed a sigh of relief,” Offit said.

The best firewall for vaccine hesitancy? Experts agreed: an overwhelmingly safe and effective vaccine. And in early November, less than a week after the presidential election, Americans got just that. Within days of each other, both Pfizer and Moderna unveiled data showing their vaccine was indeed safe and more than 90% effective.

“We heard people jumping up and down and hugging and kissing,” said Dr. Albert Bourla, the CEO of Pfizer, reflecting on the moment his team learned of the results. “Then reminding yourself to wear your mask before you kiss me, and all of that.”

Fauci described the moment he learned of the trial results as a sign that the end could be near.

“I was at my next door neighbor’s having a physically, socially distanced sit down on a Sunday night when I got a call from the CEO of Pfizer, Albert Bourla, saying, ‘Tony are you sitting down?’ And I said, ‘Uh, no, but I will,’” Fauci said. “And when he said, it’s 94-95 percent effective, I said, ‘Oh my goodness gracious, this is it. This could be the beginning of the end of this ordeal that we’re in.’”

Just over four weeks later, Pfizer’s product is being shipped across the country, and emergency authorization for Moderna’s vaccine could come as early as this week.

'Bizarre moment' of despair and hope

With a major breakthrough in the vaccine’s development, attention has turned in recent weeks to the daunting task of distributing the product across the country – from major cities struggling with hospital capacity to rural outposts so often neglected in public health.

The challenges ahead may be exacerbated by a change in leadership in Washington, DC, with President-elect Joe Biden poised to take control of the national response on Jan. 20.

“Vaccines in and of themselves don't save lives. Vaccination does. And that's where the hard work really begins,” said Dr. Marcella Nunez-Smith, a medical adviser on the Biden transition team. “There are many questions that remain about manufacturing capacity, the ability to distribute equitably and efficiently, and ultimately to get everyone vaccinated.”

The vaccine breakthrough may have come just in the nick of time. As the new year approaches, thousands of American lives continue to be lost each day – with devastating and record-breaking case and hospitalization figures rolling in day after day.

Indeed, Dr. Robert Redfield, the head of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), said the U.S. could see more deaths per day than 9/11 or Pearl Harbor for the next 2-3 months.

“We're in this bizarre moment right now,” said Nunez-Smith, an associate dean at Yale University School of Medicine, “where we have a hope at the same time that we recognize that we see surges happening simultaneously across the country.”

Despite the anticipation of dark days ahead, officials responsible for the vaccine effort remain steadfast in their confidence of finishing the job.

“At the end of the day, you know who's going to win: the American people,” Perna said. “Because of this great effort, right? So I'm pretty proud of what we've accomplished. The American people will win.”

ABC News’ Oliver Agger, Katherine Aimateen, Ava Anderson, Nicole Azevedo, Kevin Bartels, Erica Baumgart, Paulo Bolivar, John Breitling, Alyssa Briddes, Ely Brown, Zoe Chevalier, Jeanmarie Condon, Matt Cullinan, Anne Flaherty, Kaitlyn Folmer, Andrew Fredericks, Halley Freger, Cindy Galli, Dylan Goetz, Megan Harding, Brian Hartman, Sally Hawkins, James Holbrook, Alex Hosenball, Jackie Hurwitz Baskin, Kinga Janik, Jinsol Jung, Mary Kathryn Burke, Keith Krimble, Zoe Magee, Chris Miller, Arielle Mitropoulos, Drew Oberholtzer, Victor Ordonez, Melia Patria, Sasha Pezenik, Shane Rasco, Patrick Reevell, Ann Reynolds, Misha Rezvi, Emily Ruchalski, Tia Schellstede, Nadine Shubailat, Tonya Simpson, Eugene Song, Lucia Soven, Jenny Wagnon Courts, Teri Whitcraft, Bob Woodruff, and Zunaira Zaki contributed reporting.

This report was featured in the Monday, Dec. 14, 2020, episode of “Start Here,” ABC News’ daily news podcast.

"Start Here" offers a straightforward look at the day's top stories in 20 minutes. Listen for free every weekday on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, the ABC News app or wherever you get your podcasts.