Experts turn to antibody treatment following swarm of breakthrough COVID-19 infections

With high-risk breakthrough COVID infections, monoclonal antibodies may help.

While authorized vaccines have proven safe and effective in holding the line against COVID-19, they are not 100% effective. Reports of uncommon breakthrough cases among fully vaccinated Americans, coupled with the delta variant tearing through the country, threaten to undermine the fiercely fought wins against the pandemic.

For the fully vaccinated who do test positive, if you are at high risk for severe infection, health experts are now turning to Food and Drug Administration authorized, virus-fighting monoclonal antibodies in some cases. They are saying it's safe and beneficial for those who have been vaccinated, but get infected with COVID-19 nonetheless.

"Receiving antibody treatments in a timely manner could be the difference of ending up in the hospital or getting over COVID (quickly)," Dr. Shmuel Shoham, infectious disease physician at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, told ABC News.

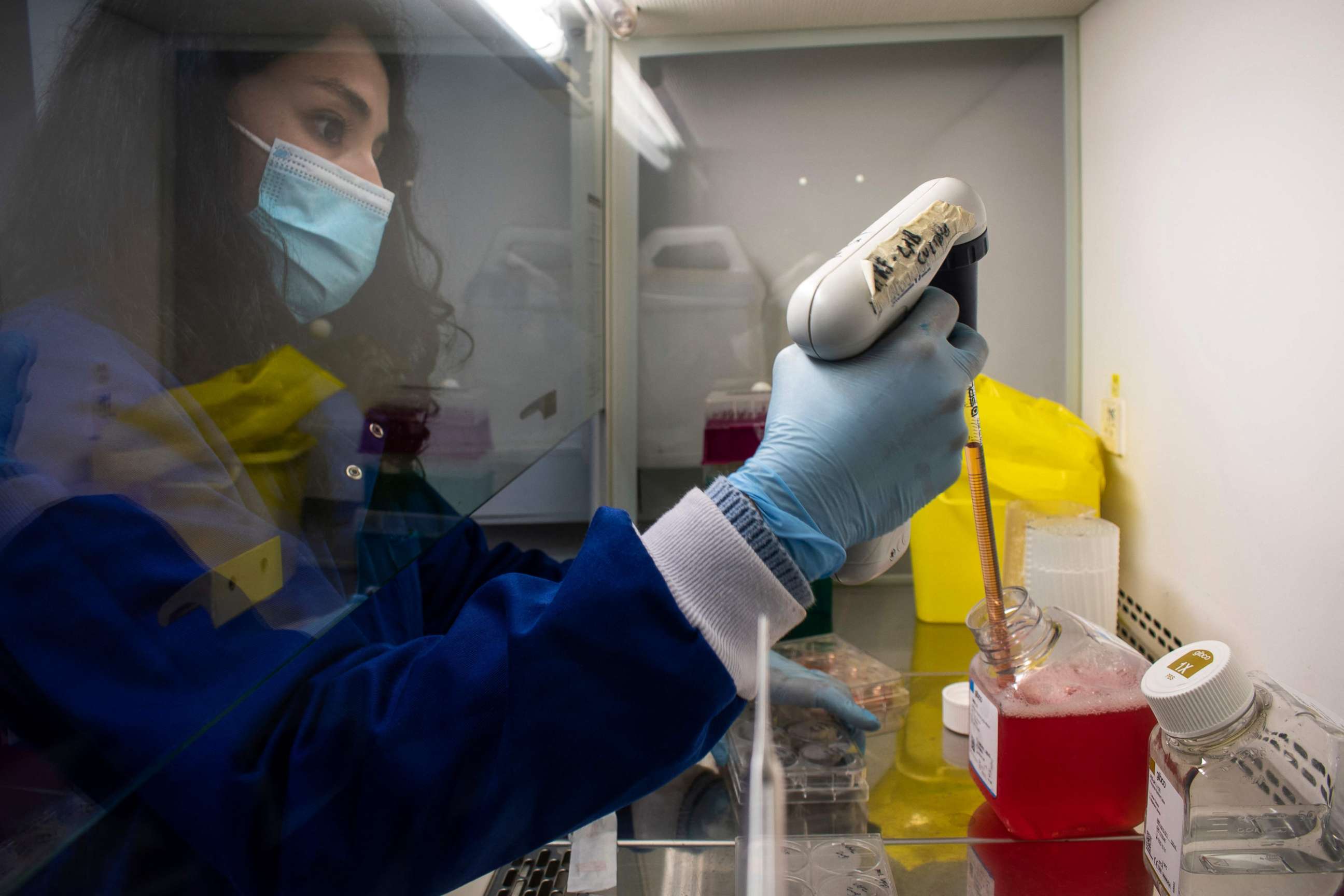

Monoclonal antibodies are synthetic versions of the body's natural line of defense against severe infection, now deployed for after the virus has broken past the vaccine's barrier of protection. The therapy is meant for COVID patients early on in their infection and who are at high risk of getting even sicker to help keep them out of the hospital. This risk group includes people 65 and older, who have diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiac disease, obesity, asthma or who are immunocompromised.

It can be administered through an intravenous infusion, or a subcutaneous injection, which is less time-consuming and labor-intensive, and more practical in an outbreak situation.

The therapies still in use across the U.S., like Regeneron's antibody cocktail, has shown to hold up against the variants of concern, including delta.

It's a new use for a therapy whose authorization predates that of the vaccines.

"The trick is to proverbially cut the virus off at the pass," Dr. William Schaffner, professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, told ABC News. "An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure."

Though a fraction of breakthrough cases have symptoms, the few that do may need backup to fight off the infection, experts say.

"There are exceptions. Everyone has seen a handful of patients who are vaccinated, you get very, very sick. Those are by and large, people with many risk factors, and perhaps people were vaccinated longer ago, with people in whom we don't expect the vaccine to work as well," Dr. Andrew Pavia, Infectious Diseases Society of America fellow, NIH COVID treatment guidelines panel member and chief of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Utah School of Medicine said.

Clinical trials for monoclonal antibody therapies were conducted prior to vaccines' authorization, before shots started going into arms and far before breakthrough infections were a part of daily discussion. But the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention specifies that for vaccinated people who have subsequently contracted COVID, a vaccine should not preclude seeking further treatment.

"Prior receipt of a COVID-19 vaccine should not affect treatment decisions (including use of monoclonal antibodies… or timing of such treatments," the CDC said.

The chances of an allergic or adverse reaction is low, experts said. Regeneron's product targets the virus, not a protein produced by the body, a company spokesperson said -- so, it likely wouldn't trigger a haywire immune response with an antibody "overdose" from both the vaccine and the monoclonal therapy. And clinical trial data has shown authorized monoclonal antibody therapies can sharply reduce hospitalizations and deaths by as much as 70%.

A Regeneron spokesperson said as long as a patient has tested positive for COVID and meets the other criteria to receive the treatment, they can receive the therapy.

"We are not screening those patients out. If they have been vaccinated and come in testing positive and are at high risk for a more severe infection we are giving them monoclonals," Schaffner said. "I think that was decided pretty quickly."

It's a question of targeting the appropriate group of infected patients, experts said and it's not for anyone who has symptoms after testing positive. Doctors prescribe the therapy for patients with specific risk factors that make them unlikely candidates for fighting off the virus on their own. With your antibodies already being made to combat coronavirus, experts said another helping won't do as much good.

But Shoham calls it a "missed opportunity" for patients eligible to receive it -- who don't.

"If they had gotten a monoclonal antibody, their chance for hospitalization would have been significantly reduced," Shoham said.

"The vaccines are so good, that most people who have one or two risk factors that are vaccinated are less likely to become infected, and if they are -- the vast majority have done very well," Pavia said. "What we're trying to do is identify that small sliver of people with breakthrough infection that may get quite sick."

The antibody cocktail medications work best if it is delivered within days of a positive test or onset of symptoms. So, doctors recommend acting quickly after getting a positive test to seek treatment, if the high-risk criteria fit -- whether you have been vaccinated or not.

"This is a targeted treatment that is not for everyone -- it's not 'spaghetti at the wall' for when vaccines don't work," Schaffner said. "But this is good news on the therapeutic side."

ABC News' Eric M. Strauss contributed to this report.