Conservatives confront moral dilemma of vaccines and treatments derived from fetal tissue cells

Race against COVID-19 raises deep debate at the nexus of experiment, ethics.

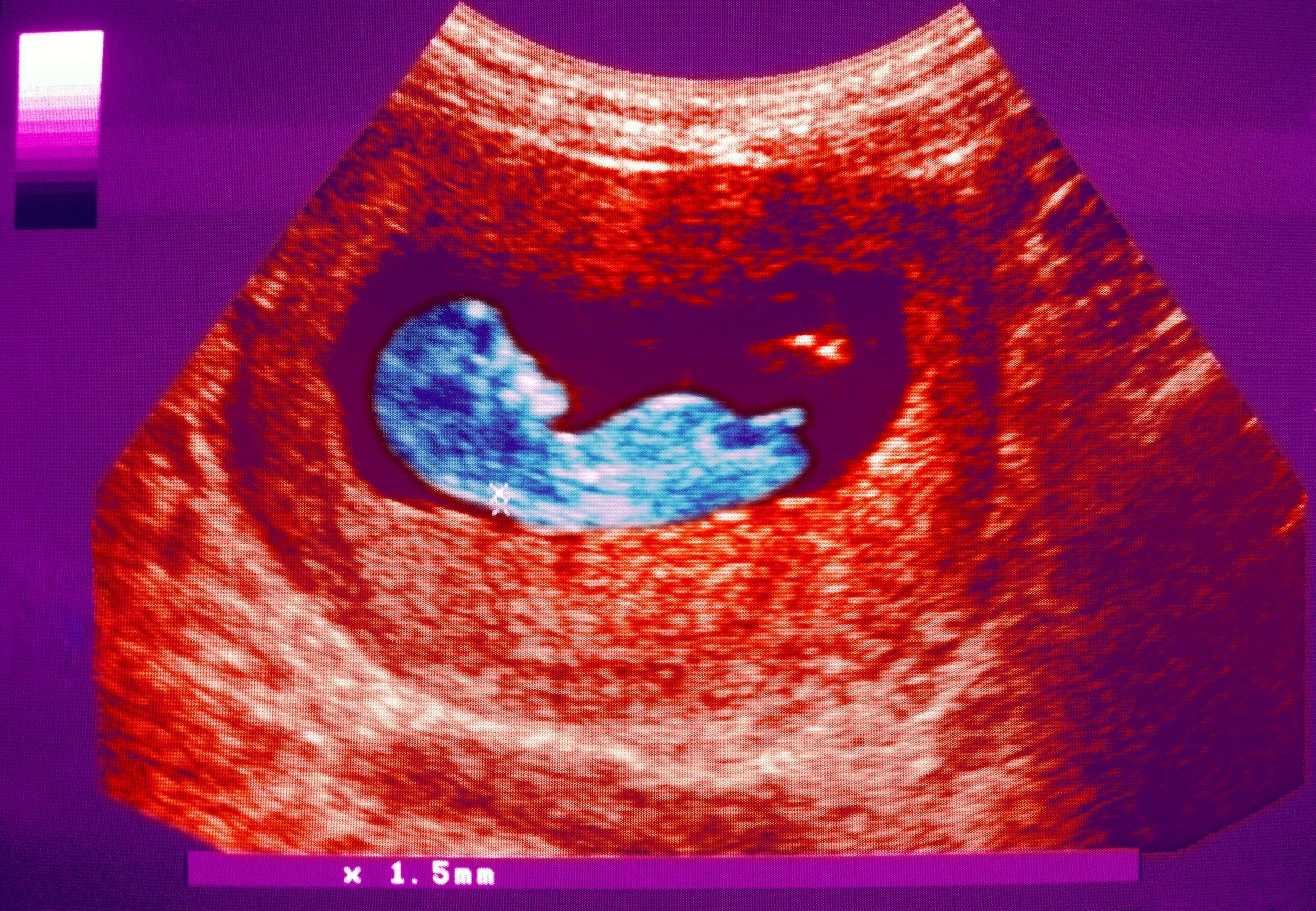

The race to develop vaccines and treatments for COVID-19 has newly highlighted a longstanding dilemma for religious conservatives: much of the cutting-edge research relies on the use of material derived from human fetal tissue -- something they have spent years fighting against.

In interviews with ABC News this week, leaders in the Catholic Church and other anti-abortion advocates say they aren't ready to dismiss the latest scientific discoveries that could save countless lives. But they also are quick to note that much of the new findings could be what they consider ethically "tainted."

"There's a lot of concern and interest in this issue -- what's the vaccine going to look like? What kind of moral choices are we going to have before us?" said Greg Schleppenbach, the associate director of Secretariat of Pro-Life Activities with the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

At issue is the use of cells derived from human fetal tissue to discover, develop and test medical innovation -- something scientists agree is often necessary in the most groundbreaking medical advances.

Recent polling reveals a split amongst Americans: roughly 6 in 10 adults say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while 38% say it should be illegal in all or most cases.

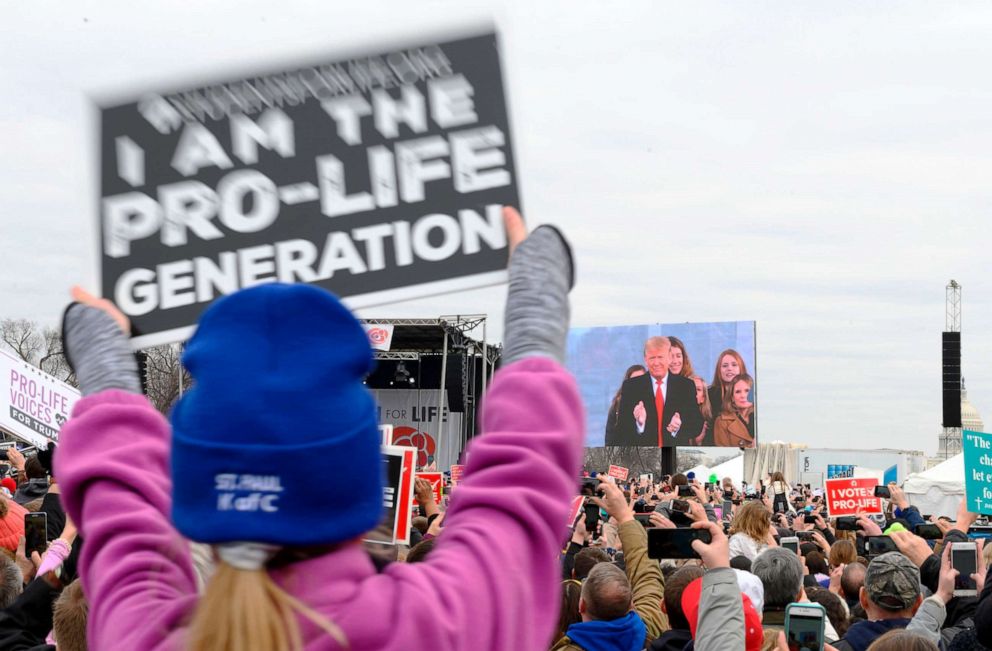

During his political career, President Donald Trump has assumed a staunchly anti-abortion stance. In 2019, his administration suspended federal funding for research reliant on new fetal tissue cells derived from an elective abortion, while allowing for previously established cell lines. Fetal tissue from miscarriages are permitted under this statute, although many scientists say it's difficult to use because there are often abnormalities and other issues.

In early 2020, The Trump administration created a new federal ethics board to review proposed fetal tissue research grants. Of the 15-person board, 10 have records of opposition to abortion, fetal tissue research or both.

Conservative groups long-opposed to abortion have advocated against what they call "ethically problematic" fetal material -- tissue obtained via elected termination of pregnancy, and cell lines descendent from them.

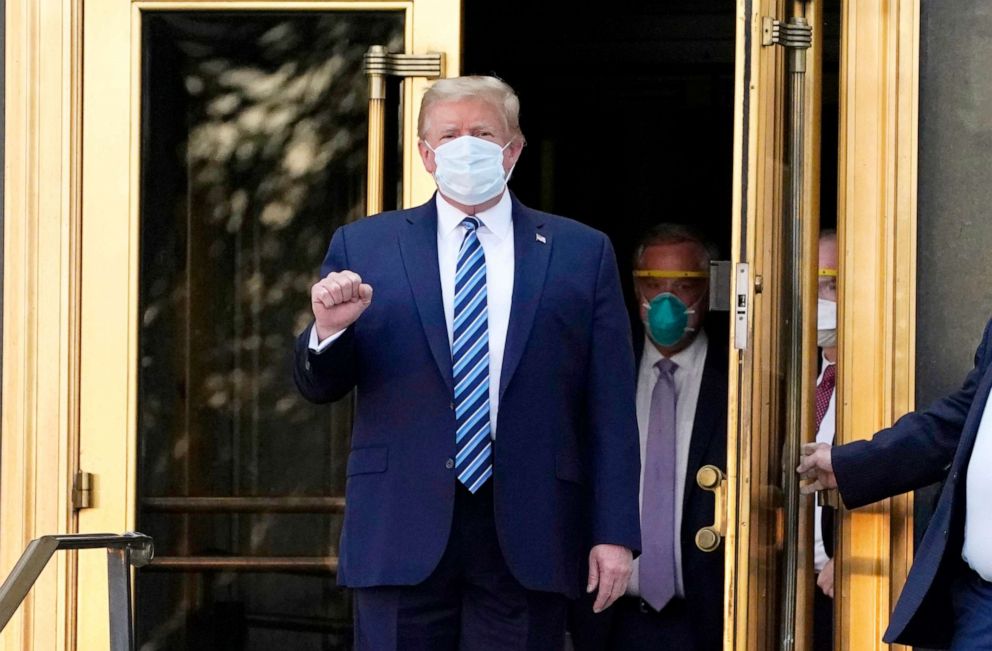

It's not a simple ask: some of the most commonly used cell lines in medical research originated that way. The experimental antibody treatment from Regeneron that was taken by Trump to treat COVID-19 was developed using cells derived originally from human kidney tissue taken from an aborted fetus in the 1970s. Several of the vaccine candidates for the virus also use that line.

The cells from that tissue, the HEK293T cell line, have continued to divide and grow in a culture, and have been used in scientific discovery, for decades.

Regeneron says it does not consider the treatment to have relied on fetal tissue, since the cells were acquired so long ago.

They "are considered 'immortalized' cells (not stem cells) and are a common and widespread tool in research labs," a Regeneron spokesperson told ABC in a statement. The cell line "wasn't used in any other way, and fetal tissue was not used in this research."

Social conservatives view research with fetal tissue as unethical and have long disputed taxpayer money's use to support it. Scientists counter, controversy aside, that countless important medical discoveries have relied on fetal tissue, leading to significant work in research and treatment of diseases like AIDS and Zika, and further, could be instrumental in combating coronavirus. Fetal tissue cells are more flexible and less specific than adult cells, and can offer a unique "blank slate" for further study and testing of new therapeutics.

"Fetal tissue has unique and valuable properties that often cannot be replaced by other cell types," the International Society for Stem Cell Research urged the new Trump ethics board in July, adding, it "remains the gold standard for evaluating the accuracy of models of human fetal development."

Lying at the crux of the contention -- how that material is obtained. Under current statute, tissue from "spontaneous" abortions, or miscarriages, are permitted. But those moments often occur not in hospital -- rather, at home -- making proper sample collection difficult, experts say, in what poses an already brief window of time before the cells are degraded. And, miscarriage often occurs because of complications during fetal development which prevented it from surviving to full term. Thus that tissue would offer limited use, unless it was that specific abnormality a scientist had hoped to study.

'Gradations of cooperation'

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has advocated for at least one COVID-19 vaccine to be developed completely free from connection to aborted fetal cells. In April, the USCCB sent a letter to FDA commissioner Stephen Hahn, urging, "no American should be forced to choose between being vaccinated against this potentially deadly virus and violating his or her conscience."

Rev. Dr. Tadeusz Pacholczyk, director of education at the National Catholic Bioethics Center and member of a federal ethics advisory board on the matter, told ABC: "The decision by companies to intentionally utilize these problematic cell lines results, if there are no alternatives, in a kind of moral coercion."

Still, other anti-abortion conservatives say that the cell line used to develop the vaccines or treatments for COVID poses less of a moral dilemma than if it had come directly from an aborted fetus.

Dr. G. Kevin Donovan, director of the Pellegrino Center for Clinical Bioethics, professor of pediatrics at Georgetown University, said it's not a clear-cut issue.

"There are gradations of cooperation," said Donovan, also a member of the Trump administration's fetal tissue ethics advisory board.

"Some of them are so remote to what you see is the original evil act, that you can be morally justified in accepting some necessary, lifesaving good that comes from it," he added. "Not just for you, but by being immunized, you're also not going to spread the virus to other people."

Trump faces criticism for use of Regeneron

Several scientific experts have criticized Trump for taking a treatment drawn from the research his administration has worked to curtail.

"President Trump has been an outspoken opponent of fetal tissue research -- and he used it. I just think it's incredibly hypocritical across the board," Dr. Lawrence Goldstein, fetal tissue ethics board member and senior faculty member at the University of California at San Diego. He told ABC, the board was "stacked with anti-fetal tissue research members," who "rejected virtually every proposal it saw."

"The most outspoken opponents [of fetal tissue research] are now just averting their eyes, pretending it doesn't exist, and saying, well, it happened a long time ago, and we have no choice, we've just got to deal with it," Goldstein said. "There's a bit of a bind here."

Deepak Srivastava, president of the Gladstone Institutes and immediate past president of the International Society for Stem Cell Research, noted that if the Trump administration's ban was in place when the cell line Regeneron used was made -- the innovations that have come from it would not have been possible -- including testing the treatment Trump received.

"It's just tremendous hypocrisy," Srivastava said. "It would not be available to make the drugs that we've had -- and Trump would not have received those antibodies."

Those who support banning abortion argue if there is an inconsistency with COVID-19 research, it rests with the federal funding fueling vaccine development that utilizes abortion-derived cells.

"You're funding that which you say should not be funded," Pacholczyk said. "And that's a concern."

Ethical issues 'fairly nuanced'

In August, the ethics board rejected funding for nearly every proposal involving fetal tissue: 13 out of 14. No COVID-19-related proposal was reviewed, several of the board members confirm to ABC, though they were unsure why that was. The NIH told ABC none of the projects recommended for funding that proposed to use human fetal tissue were COVID-19 related, adding, "There is no special review process" for COVID-19 projects involving human fetal tissue.

Medical experts on both sides of the issue affirm the importance of fetal tissue in scientific research, entrenching the ethical tug-o-war.

"It's an ethical dilemma of competing goods, how tainted they are," said Dr. Greg Burke, co-chair of the Catholic Medical Association Ethics Committee. "In medicine, that sanctity of life argument is a powerful one. Not everybody agrees, obviously. So then how do we balance where we can't go out and live without somehow interacting, being tainted by things we would consider immoral or unethical?"

Those ethical concerns raised by the use of human fetal cell lines are "fairly nuanced," said Dr. Maureen Condic, NIH ethics board member and associate professor of Neurobiology and Anatomy at the University of Utah School of Medicine.

Condic noted that the HEK293T cell line is so widely in use for decades that she said it's essentially a "component of every single type of basic biological research and all types of medical research."

"They create a lot of concern for people," she acknowledged. "But then, if that's the ethical question, then do you disavow any interaction with the medical profession, period, where you might be complicit in the utilization of a cell line that is so widely in use? It's essentially impossible to avoid it."

ABC News' Eric Strauss and Sony Salzman contributed to this report.