NIH panel members speak out about 'insufficient data' on plasma treatments

The FDA's emergency authorization for plasma has garnered criticism and praise.

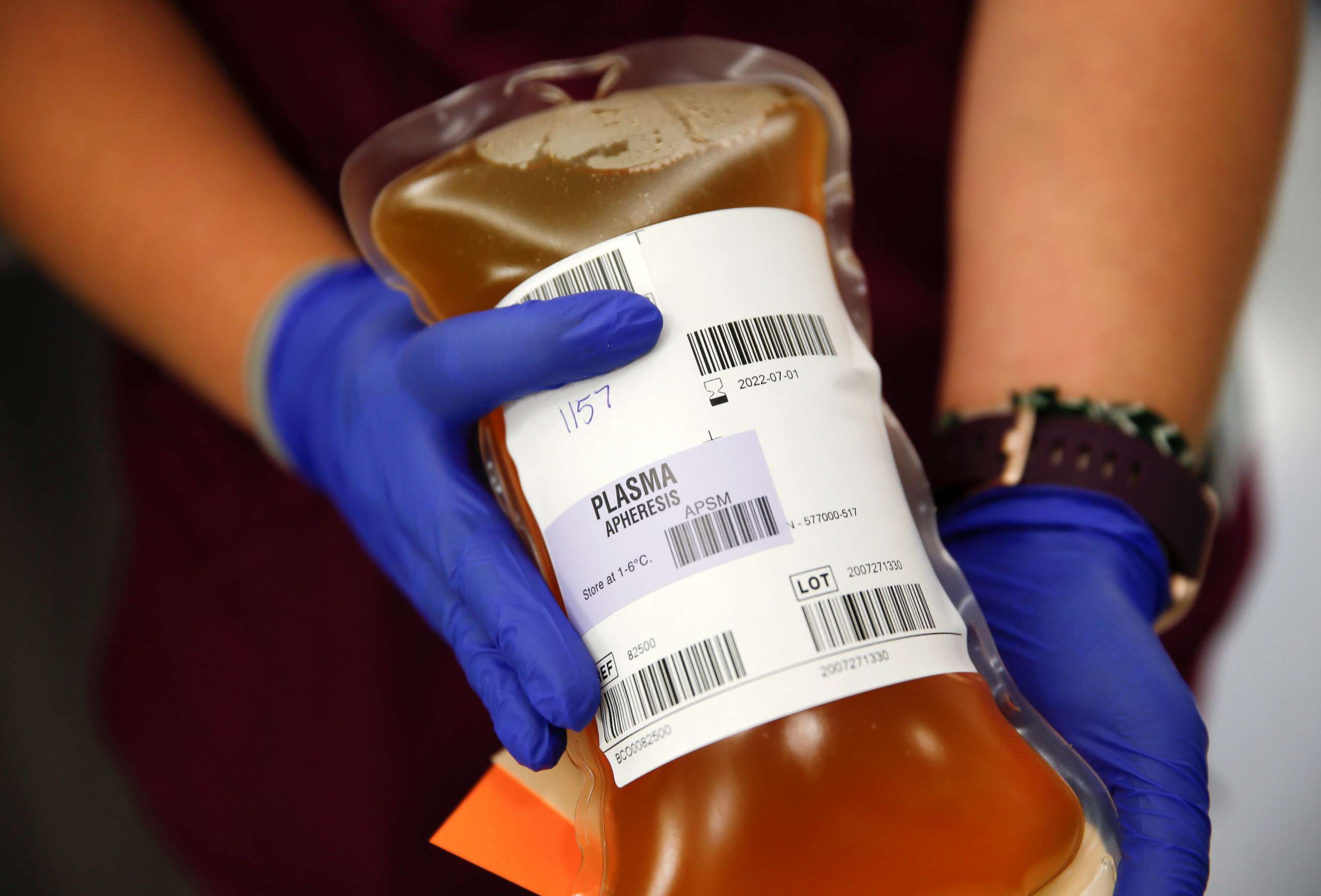

As medics and scientists decide whether convalescent plasma can be used as a treatment for COVID-19, both confidence in and criticism for the method have grown.

Amid what's become a heady infusion of hope and politics, public health experts tasked with shaping treatment guidelines now find themselves compelled to clarify the state of science as it stands, and cut through the noise.

On Aug. 23, the Food and Drug Administration issued an emergency authorization for plasma, arguing the potentially promising treatment is safe enough to merit broader use.

President Donald Trump championed the FDA's authorization as a "historic announcement" for a therapy with an "incredible rate of success," but a panel of experts convened by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) put out a memo Tuesday saying there is "insufficient data" recommending either for or against convalescent plasma as treatment of COVID-19.

The note instantly set off a flurry of criticism and speculation about further inter-agency friction. In reality, the NIH's carefully-worded message about convalescent plasma's promise is almost identical to the language in the fine print of the FDA's emergency authorization: that plasma should not be considered the medical standard of care, because there's no proof yet that it works.

Three experts interviewed by ABC News who sit on the NIH panel felt compelled to emphasize the fact that plasma's efficacy has not been proven -- and push back against what they agreed was a confusing message kicked up in the wake of the FDA authorization.

Much of the confusion stemmed from FDA Commissioner Steven Hahn himself, who initially said plasma demonstrated a 35% reduction in mortality -- a gross mischaracterization of the evidence which he later corrected in an apologetic tweet.

After the FDA's announcement, those on the NIH's treatment guidelines panel said their memo now is aimed at maintaining -- and building back -- the public trust at risk of eroding in the political undertow.

"We've made our careers on honest appraisal of science," Dr. Mitchell Levy, chief of pulmonary critical care at Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, told ABC News. "COVID-19 has been politicized more than any other disease I've ever seen in my lifetime. But we need to make sure it's understood that the FDA empowering the plasma emergency authorization doesn't mean that everyone should get it -- it's that everyone can get it. But that's where it's easy to take it and run with it. This is where politicization plays in -- people can read into it however they like, based on their biases."

Experts understand the FDA's decision: Plasma's newfound emergency authorization will make it more accessible for COVID-19 patients who are severely sick and looking for a safe therapy that might help.

But health officials also worry the authorization may make it harder to complete those ongoing, placebo-controlled studies that are desperately needed to understand the true benefit of the treatment.

"I don't think the emergency authorization was a mistake, but it could make it more challenging to complete randomized clinical trials," Levy said. "Being clear and maintaining that public trust is so important. Reassuring the public what's safe, and that the data is not convincing enough, yet."

"We have to sort through and see what works, what's safe, what's promising but unproven -- and what's been proven not to work," said Dr. Andy Pavia, of the University of Utah School of Medicine.

"We can't say it doesn't work, but we can't say that it does work. That is the perfect situation to do a clinical trial," said Dr. Rajesh T. Gandhi, of Harvard Medical School. "But there is a dilemma which is that if clinicians don't refer patients, don't enroll patients… we don't get an answer and we won't make progress. You've got to be guided by the science."

Concern that an FDA emergency use authorization might impair both public and scientific understanding of plasma's promise loomed over the decision to roll it out. Sources familiar with the matter told ABC News that when Dr. Francis Collins and Dr. Anthony Fauci became aware that the FDA was considering the authorization, they argued forcefully against it, troubled at the hindrance it could pose in determining the control trials' efficacy.

And yet, Trump appeared to push the FDA in the opposite direction, accusing the "deep state" FDA on Twitter of putting their thumb on the scale against advancing new vaccines and therapeutics until after the election.

A day later, the emergency authorization was announced with much fanfare from Trump -- who had Hahn at his side. Hahn quickly backtracked after questions were raised about his rhetoric lauding plasma's proof, and said criticism about his characterization was "entirely justified."

Seeking to quell some of the confusion, Levy, Gandhi, Pavia and the other members of the NIH panel carefully reiterated: Plasma should not be considered a gold-standard COVID-19 treatment until it's proven to work.

"There is such a difference between the cautious and scientifically grounded language of the emergency authorization and the announcements that were made," Pavia said. "People put a lot of faith in the FDA's cautious and balanced approach to efficacy and safety, and once politicians start to interfere in that process, you're in a strong risk of losing that trust."

Panel members expressed concern that rhetoric could skew the perception of fact and presage political pressure. But, they did say that they're committed to upholding a firm infrastructure of fact.

"The more good information we're armed with, the better we'll be," Pavia said. "We have some reason to be optimistic, but we've got to keep an open mind until all the data are in. We need trustworthy answers, to keep up with the clinical trials, and meanwhile, you've got to take care of patients and make the best decisions you can. But we can't stop going toward the right answers."

ABC News' Anne Flaherty contributed to this report.