Doctors fear shortage of drug critical to ventilator treatment for coronavirus

With much-needed equipment comes demands to put it all to use.

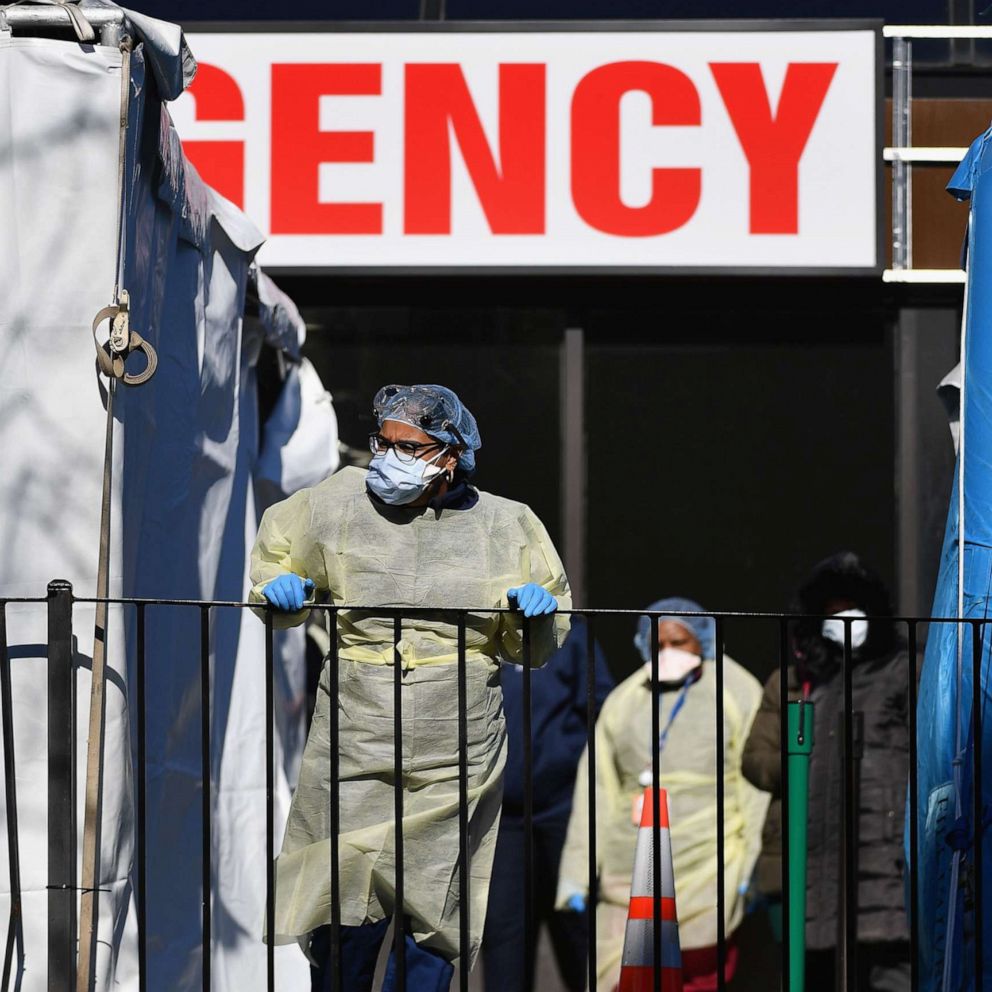

As states sound the alarm over a lack of ventilators to help hospitalized novel coronavirus patients -- including a plea for 30,000 machines for New York state alone -- experts warned that even if the equipment arrives, facilities could face a shortage of health care workers trained to use them.

"If you have a thousand more ventilators magically appear, do you have the 20 ICU [Intensive Care Unit] doctors, 300 ICU nurses, 150 respiratory therapists and all of the [personal protective equipment] needed to support those 1,000 new ventilators?" Dr. Doug White, an intensive care physician with the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, told ABC News. "Simply put, ventilators don’t run themselves."

Personnel specially trained to treat patients with ventilators is just one of the latest possible second-order shortages that government and hospital officials are discovering as the battle against the coronavirus relentlessly drags on, a list that some doctors now say also includes critical drugs used to sedate patients who need to be intubated as part of their treatment.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo on Monday called on other states to send as many health care workers as they can to assist the strained system in his state.

Tune into ABC at 1 p.m. ET and ABC News Live at 4 p.m. ET every weekday for special coverage of the novel coronavirus with the full ABC News team, including the latest news, context and analysis.

There are approximately 6,800 licensed respiratory therapists in New York state, according to the state's Education Department, which handles professional licensing. They are specialists who closely monitor patients and adjust treatments using the lifesaving -- and in some cases highly sophisticated -- ventilators to breathe.

But even with the addition of hundreds of respiratory therapists expected to graduate from schools in New York this spring, the help of anesthesiologists and other physicians freed up by the postponement of elective procedures and tens of thousands of volunteer health care workers, health officials remain concerned about personnel shortages. They could limit hospitals’ abilities to treat patients at the peak of the outbreak in the state and nationwide that could be as many as two weeks away. Experts said those with specialty training are key.

New York state counts more than 75,000 cases of coronavirus infections so far, according to Cuomo. Nationwide, over 186,000 people have tested positive for the virus and more than 4,000 have died, according to a count by Johns Hopkins University.

Cuomo said Tuesday that in New York state 2,710 patients were currently in the state's intensive care units and nearly 300 had to be intubated and put on ventilators.

According to medical experts, the normal standard of care for a ventilated patient includes around-the-clock care from a team of nurses and respiratory therapists, under the supervision of an intensive care doctor.

Now, due to the influx of patients needing ICU care, one ICU doctor may now manage four times the number of ventilated patients they normally do, with a team of non-ICU specialist doctors working underneath them.

It's a strained system that could buckle even further if large numbers of front-line nurses and doctors contract the coronavirus due to shortages of personal protective equipment.

"This will likely result in a lower quality of care, and [it's] why the standard of care changes in an emergency," said White. "Critical care physicians are trained in respiratory and multi-organ failure in a way that no other specialty is."

When those physicians are transitioned from being directly involved to now managing a group of non-ICU doctors, it changes the care the patient gets, he said.

Dr. Greg Martin with the Society of Critical Care Medicine, a professional organization devoted to the care of the most critical patients, said it’s hard to project which workforce of the three -- doctors, nurses and respiratory therapists -- will be the first to become stretched. But he speculated it would be the 28,000 intensivist physicians or ICU doctors who work in the U.S.: "You will realize you can’t rely on the intensivists to be available for every patient."

Roughly 5,800 nurses in New York state are critical-care certified, according to the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Some 120,000 are credentialed for acute and critical care nationwide, the group said.

"You can’t win a war with no troops," Dr. Peter Papadakos, the director of critical care medicine at the University of Rochester Medical Center, told ABC News about the potential personnel shortage. "You can have fancy equipment, but if you don’t have any troops and if you don’t have any gasoline ... you lose the war."

Doctors fear drug shortages after 'tsunami of patients'

At Elmhurst Hospital in the borough of Queens in New York City, said to be the "ground zero" of infections in the U.S., the problem isn't a shortage of ventilators or even people -- it's drugs used to sedate patients when they're intubated, along with the equipment used to deliver those drugs, according to a doctor who works there.

In another New York City ICU, a critical care physician told ABC News their hospital is also having to confront drug shortages, including those used to sedate patients.

"If you aren’t sedating someone enough, you always run the risk of someone self-excavating, which is ripping the tube out of themselves because they’re too awake," the physician said.

When a patient is intubated, they are usually given a combination of sedatives and anesthetics before a breathing tube is inserted down their throat. Patients sometimes also require paralytic drugs to loosen up their vocal cords and other muscles to prevent damage when the breathing tube is inserted.

Patients continue to receive sedatives and pain relievers to keep them asleep while intubated, to prevent their bodies from fighting against both the breathing tube and the ventilator, which performs breathing functions for patients to allow their own lungs to heal.

With many COVID-19 patients requiring ventilators for weeks, some health officials are worried that the nation’s supply of necessary drugs won’t be enough to help the country weather a prolonged and sustained outbreak across multiple cities and states.

Dr. Erin Fox, who tracks and investigates drug shortages reported from hospitals around the country, told ABC News that some of the most commonly used drugs to intubate and maintain a patient on ventilator are running in short supply.

"We see a tsunami of patients coming our way, and we don’t see a tsunami of drug availability coming our way. It’s scary to think, you might not have enough medicine," she said.

Three of the drugs reportedly in short supply, according to Fox, are the sedative etomidate, an anesthetic ketamine and a muscle-relaxing medication called rocuronium. Several hospitals with whom ABC News spoke said they were running low on the critical medications.

While doctors and hospitals have the ability to use alternative drugs in some cases to help intubate and sedate patients, experts worry that a prolonged worldwide outbreak could severely stretch the global pharmaceutical supply chain, forcing countries to fight among one another for resources as several states have been forced to do for protective equipment in the U.S.

The American Society of Health System Pharmacists runs the database that monitors drug shortages reported from their 55,000 members across the country who work in hospital pharmacies. The demand for drugs is not just in hot spots, but nationwide.

"With all this surge capacity that's being built, do we have the drug supply to match it? Right now the answer appears to be 'no,'" said Dr. Michael Ganio, a senior director with the society.

At one health system that runs over 40 hospitals in Ohio and Virginia, a pharmacy director told ABC News they are starting to see shortages in medications used to sedate patients who are ventilated. Their pharmacy team is already coming up with contingency plans for when the preferred drugs run out.

"The problem is, we’re all using the same manufacturers and same wholesalers. We’re all competing for the same resource," the director said.

This report was featured in the Wednesday, April 1, 2020, episode of “Start Here,” ABC News’ daily news podcast.

"Start Here" offers a straightforward look at the day's top stories in 20 minutes. Listen for free every weekday on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, the ABC News app or wherever you get your podcasts.