In Colombia, years of frustration trigger violent protests following tax proposal

Protests that began on April 28 show no sign of ending soon.

Fueled by frustration over recently proposed tax increases that critics say would have disproportionately impacted Colombia's middle and working classes, ongoing protests in the South American country are exposing years of unmet demands, experts tell ABC News.

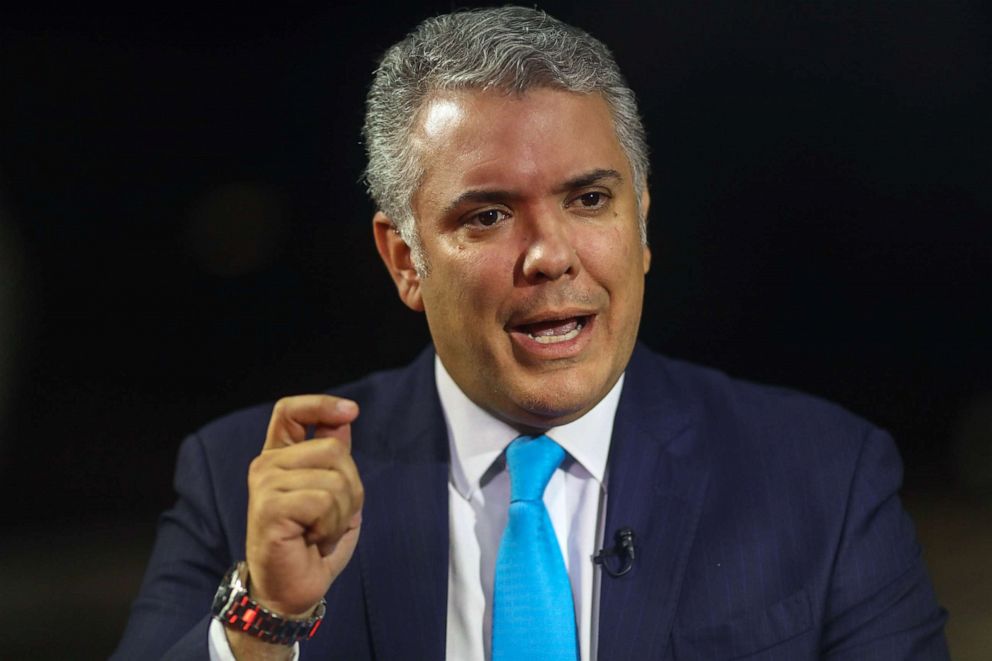

Violent protests erupted in major cities across the country on April 28, following President Ivan Duque's announcement of tax reforms that he said were "a necessity to keep the social programs going." Duque subsequently withdrew the proposed tax hikes after protests left 42 people dead and hundreds more injured -- but weeks later, demonstrations are continuing with no end in sight as protesters have expanded their demands.

Demands for higher wages, a better health care system, more job stability and more money for public education have prompted strikes and protests for many years, Florida International University professor of politics and international relations Eduardo Gamarra told ABC News.

While the majority of the current demonstrations have been peaceful, some major cities have seen businesses vandalized and several police stations burned amid violent clashes between police and protesters.

In recent days, the city of Cali, which has emerged as an epicenter of the demonstrations, has seen an increase in violence between security forces and protesters, some of them armed. Demonstrators have blocked major highways, disrupting the arrival of food and fuel supplies to the city.

"These protests are not just about the proposed tax reform," Gamarra said. "These demonstrations go a lot further back, and right now the pandemic has exacerbated many of the problems that people are frustrated about."

The issue of police reform in particular has emerged as a vital issue for protesters, Gamarra said.

"Colombia's police force was one of the most trusted in the early part of the century," said Gamarra. "And now, there is an incredible level of distrust of the police."

According to Temblores, a non-governmental organization that tracks allegations of police abuse, there have been more than 1,800 alleged cases of police violence since the marches began.

The protests are taking place as coronavirus infections reach record levels in Colombia, where nearly 80,000 people have died from COVID-19. Over the past week the country has averaged more than 15,000 new cases a day.

Arlene Tickner, a political science professor at Bogota's Rosario University, told ABC News that many of the demands from the protests stem from the issues that were supposed to be addressed with the nation's 2016 peace deal.

The landmark 2016 peace accords with the country's largest guerrilla group -- the FARC, or Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia -- aimed to "strengthen democratic institutions that were under attack and bring more jobs and opportunity to people," Tickner said. But it's only resulted in empty promises, according to Tickner.

"You have unemployment and inequality which are historically high, as well as increased levels of political violence that have grown during the pandemic, on top of the wide range of social, economic and political grievances," Tickner said. "The unpopular tax reform was just a spark that resulted in the current wave of protests."

While the tax hike was supposed to be a solution to maintain vital social programs like cash support for the unemployed and credit lines for businesses, Tickner told ABC News that the government could have chosen to tax the wealthy instead of implementing a tax hike on working people.

"The government is doing what is easy, which is to tax employees, working people who are struggling," Tickner said.

Last week, after withdrawing the proposed tax reform, President Duque invited representatives from all political parties to participate in a national dialogue.

"I want to announce that we will create a space to listen to citizens and construct solutions oriented toward those goals, where our most profound patriotism, and not political differences, should intercede," Duque said in a video.

But critics say that Duque's call for a national dialogue is just a repeat of the one he called for in 2019, after days of anti-government protests.

"That will not go anywhere. People are fed up with the empty promise that things are going to change," said Sergio Guzmán, director of the political consulting firm Colombia Risk Analysis. "We are at a standstill."

The 2019 protests themselves followed earlier demonstrations against police corruption and abuse, systemic issues that critics say have only increased.

"The poorest sectors of Colombia have the highest rates of violence, and the government has not come up with systemic solutions to address their concerns," said Guzmán. "You have all of these people who are tired and whose lives have been made more difficult."

Tickner told ABC News that the current protests have also been fueled by Duque's relationship with former President Álvaro Uribe. Duque is an acolyte of the former president, a U.S. ally who fought the FARC using brutal tactics that resulted in accusations of human rights abuses.

"He was handpicked by Uribe," Tickner said of Duque. "From the beginning many questioned his fitness to govern, and now I think he has overwhelmingly proven and confirmed those fears."

Guzman told ABC News that young protesters criticize Duque for failing to fulfill campaign promises that were aimed to help poor communities.

"He is the youngest president we've had in a generation, he was supposed to be a president who really connected with the younger generation who care a lot about social and economic issues," Guzman said. "These young people on the streets want much more from their government."

"What we're seeing in these protests is a lot of younger kids who don't have access to education, who don't have jobs, essentially having nothing to lose," Tickner said. "I don't see these protests ending anytime soon and it's very scary."