Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega's complex US ties suggest lessons for Trump era, historians say

Noriega, who died Monday, worked with the CIA before being overthrown by the US.

— -- Decades before the investigation into the Trump administration's alleged ties to Russia, another major political scandal involving top White House officials, foreign governments and secret meetings rocked Washington, and Panamanian Gen. Manuel Noriega, who died Monday at the age of 83, played a role.

In what became known as the Iran-Contra scandal, the Reagan administration armed CIA-trained Contra fighters in Nicaragua using money obtained from illegal arms sales to Iran. The U.S. government also turned a blind eye in the 1980s to drug trafficking by the Contras in an effort to keep the Cold War operation going.

Now-declassified U.S. documents reveal that Noriega offered to help U.S. officials by assassinating the leadership of Nicaragua's socialist Sandinista government, training Contra fighters and letting Panama serve as a staging ground for U.S. operations, according to Peter Kornbluh, a senior analyst at the National Security Archives and a co-editor of "The Iran-Contra Scandal: The Declassified History (1993)."

But Noriega's offer for help was superseded by the Iran-Contra scandal itself, and the strongman was eventually overthrown by the United States in a violent invasion days before Christmas of 1989. He then spent years in a U.S. prison for drug trafficking.

With his death this week, Noriega's complex relationship with the United States is once again being examined, and historians say there are lessons to be learned from that relationship, as well as the Iran-Contra scandal itself.

"He was a pawn in an international game that was way bigger than him and he certainly paid dearly," said Barbara Trent, a filmmaker who directed "The Panama Deception," a 1992 documentary about the U.S. invasion.

"He was a small-time player catapulted to international fame by the U.S. government and the media to drum up support for a ruthless invasion," Trent added.

Working with the CIA

Noriega ruled Panama from 1983 to 1989. Before and during that time, he worked with multiple U.S. intelligence agencies who agreed to ignore allegations that he was a drug trafficker in exchange for a staunch anti-communist ally in Central America during the height of the Cold War.

Noriega was paid handsomely for his help, about $10,000 per month at one point, according to John Dinges, author of "Our Man in Panama: How General Noriega Used the United States and Made Millions in Drugs and Arms (1990)."

"The relationship with the CIA and the Pentagon was quite intense in the early '80s," Dinges told ABC News. "He was considered an important asset, and everyone in the documents I've read spoke very highly of him. He was trusted to the extent that you trust someone who is a paid intelligence asset."

Noriega provided information to U.S. officials on guerrilla activities, money laundering and drug trafficking. Protecting the Panama Canal Zone, which was then considered U.S. territory, was also a reason the U.S. allied itself with Noriega. The U.S. military once headquartered its Southern Command in Panama.

Noriega's relationship with the United States began long before he rose to power as the country's leader. Noriega was an intelligence officer and graduate of the School of the Americas (now called the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation), a U.S. military training program in Fort Benning, Georgia, for Latin American soldiers, many of whom went on to commit grave human rights abuses. Noriega completed courses in Jungle Operations and Counter-Intelligence in 1965 and 1967 at the school, according to the advocacy group School of Americas Watch.

"Manuel Noriega was a mid-level military officer in Panama, and at some point in his career, he was approached and recruited by various parts of U.S. intelligence,” analyst Kornbluh told ABC News. “Everybody who worked with him became convinced that he was more of a liability than an asset because he was corrupt and deeply involved in drug smuggling himself.”

Noriega worked with multiple U.S. intelligence agencies, including the CIA and the Defense Intelligence Agency. But he also continued some elements of the populist movement of Gen. Omar Torrijos, his mentor and the de-facto leader of Panama from the time he took power in a coup in 1968 until his death in a mysterious plane crash in 1981.

"Noriega was a strongman who took over a very populist movement that Torrijos had started and continued until things started to kind of fall through," filmmaker Trent said.

Noriega's own politics were sometimes complicated, although he was seen as an ally by the Reagan administration.

"He played kind of both sides: He supported revolutionary movements and supported the Sandinistas at times, he worked with the Cubans. But because Panama was so strategically placed, he became a collaborator in the Contra War with the United States," Kornbluh added. "[Reagan's team] didn't really care as much about drug smuggling as they did about seeing if they could overthrow the Sandinista government."

Offering to help the Contras

But Noriega's cozy relationship with the cartels and the killing of a top political opponent in 1985 both put his relationship with the United States in jeopardy.

In 1986, he sought to improve his relationship and image by offering to help topple the Sandinista government, Kornbluh said.

In August of 1986, Noriega sent an emissary to meet with Lt. Col. Oliver North, a security adviser to President Reagan, to propose a deal.

"He was suggesting that if the United States government agrees to help clean up Noriega's image and lift the ban on U.S. sales to the Panamanian Defense Forces, a ban that had been put into place because of the drug smuggling, Noriega offered to assassinate the Sandinista leadership for the United States government," Kornbluh said. "This proposal actually was passed around the National Security Council."

In an Aug. 23, 1986 note to his boss and Reagan's national security adviser, John Poindexter, North wrote about meeting the emissary.

"You will recall that over the years, Manuel Noriega in Panama and I have developed a fairly good relationship," North began.

He then discussed the logistics of meeting the Panamanian strongman in person.

"A meeting with Noriega could not be held on his turf -- the potential for recording the meeting is too great ... My last meeting with Noriega was in June on a boat on the Potomac. Noriega travels frequently to Europe this time of year and a meeting could be arranged to coincide with one of my other trips," North wrote.

Poindexter later replied that North should meet with Noriega, writing: "If he really has assets inside, it could be very helpful, but we cannot (repeat not) be involved in any conspiracy on assassination. More sabotage would be another story. I have nothing against him other than his illegal activities."

The two men ultimately met in London Sept. 22, 1986, according to a page from North's own notebook, published by the National Security Archives. Noriega offered to help train the Contras, allow the United States to use Panama as a staging ground and to "facilitate sabotage of a number of economic targets," analyst Kornbluh said.

"In return, the United States would restore military sales and kind of take him off their persona non grata list," Kornbluh said.

"They actually set about doing this. The White House pushed for better policy toward Panama," he added. "But very quickly, this effort to collaborate in a very highly significant way in the Contra war was eclipsed by the Iran-Contra scandal itself, which broke out only eight weeks after this meeting took place."

The alleged cover-up of the Iran-Contra affair ended in the indictment of a number of high-level White House officials, including Poindexter and North.

"Iran-Contra was a class A political scandal that went on for years and years," Kornbluh said, comparing it in some ways to the Russia investigation of today. "There are a lot of parallels here, both in the secret operations themselves and the procedural issues about addressing them."

How the Iran-Contra investigation unfolded also holds lessons for today, Kornbluh said. Poindexter and North were given immunity to testify about Iran-Contra, which ultimately led to their convictions being overturned.

"You have a situation now where Congress wants to investigate these Russian issues, and they're now in competition with a special prosecutor. That was also the case during Iran-Contra, where a congressional investigation gave immunity to people like Oliver North to talk about his illicit dealings with people like Manuel Noriega and then the independent counsel was not able, because of that immunity, to successfully put North in jail," Kornbluh said.

Both Poindexter and North were convicted on criminal charges but later had their convictions reversed, ending the saga.

But there are also important differences between Iran-Contra and the current investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election, for which the Kremlin has denied any direct involvement.

"In the Iran-Contra scandal, we knew what the illegal operations were and then we proceeded to understand more completely what the cover-up was. In this case, we're not exactly sure what the illegal operations or the crime is here,” Kornbluh said of any possible wrongdoing, “although we are seeing the cover-up basically unfold day by day. We have a cover-up in search of a crime at this point."

The Trump administration has denied allegations of illegal activity.

Overthrown by the US

In some ways, Noriega was a casualty of the Iran-Contra scandal, too. He later went on to claim that it was his refusal to help arm the Contras that led the United States to depose him, but there were many factors that contributed to the U.S. invasion.

"Noriega became the center of a perfect storm, so to speak," filmmaker Trent said. "His primary supporters in the U.S. were under indictment, he had just participated in an operation with the DEA that froze bank accounts for the first time, which was huge.

“There were a whole lot of things that happened simultaneously that helped make this invasion more possible and, of course, the biggest thing was the media just banging the drums for war."

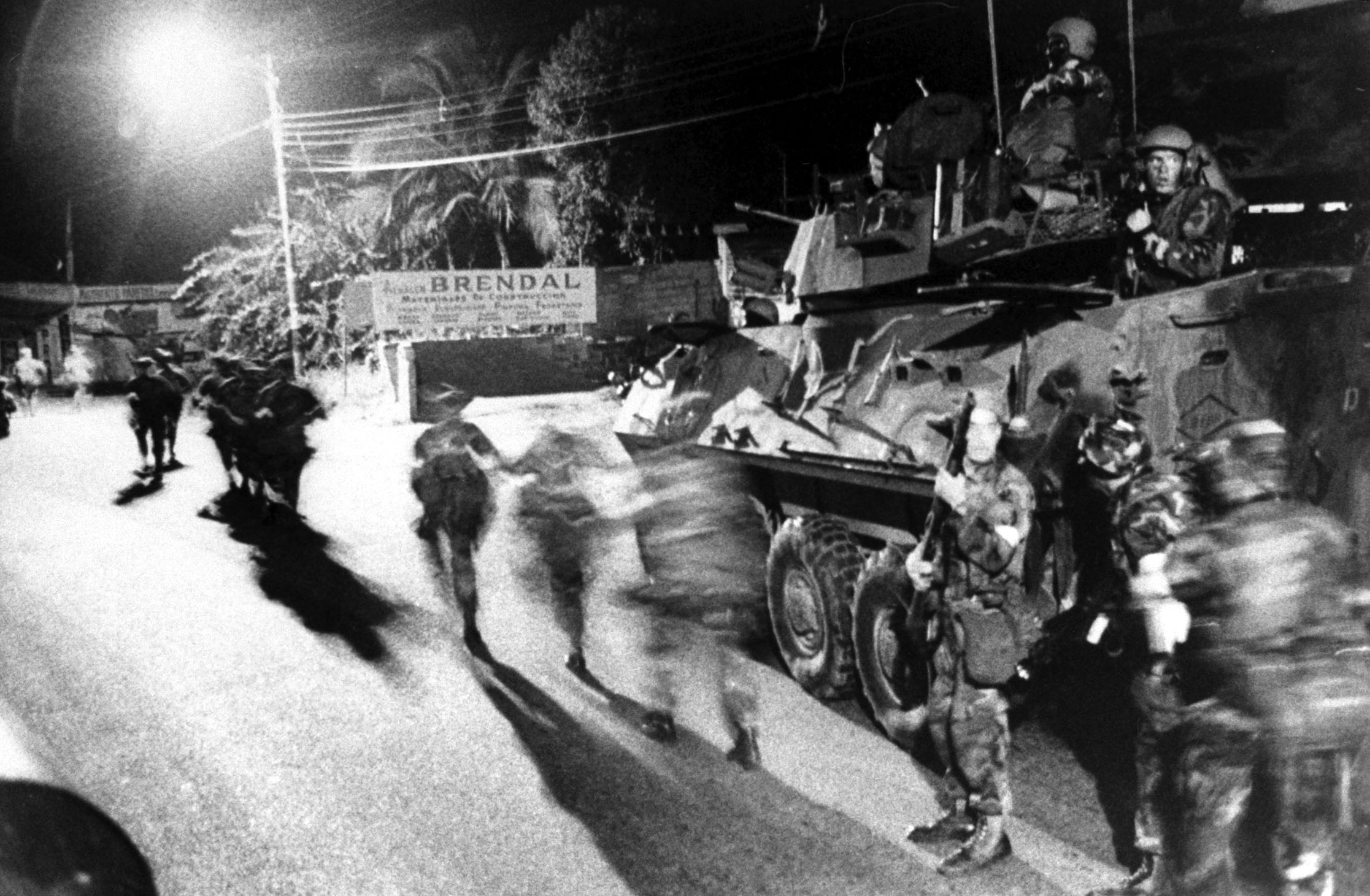

Code named "Operation Just Cause," the invasion involved nearly 26,000 U.S. troops. Questions still remain about the number of people who were killed, injured or suffered other human rights abuses during the invasion.

There are conflicting estimates from the U.S. military and Panamanian human rights groups about the number of people killed, ranging from a few hundred victims to thousands. In July of 2016, the Foreign Ministry of Panama issued an executive order creating a new truth commission to investigate the full impact of the 1989 invasion.

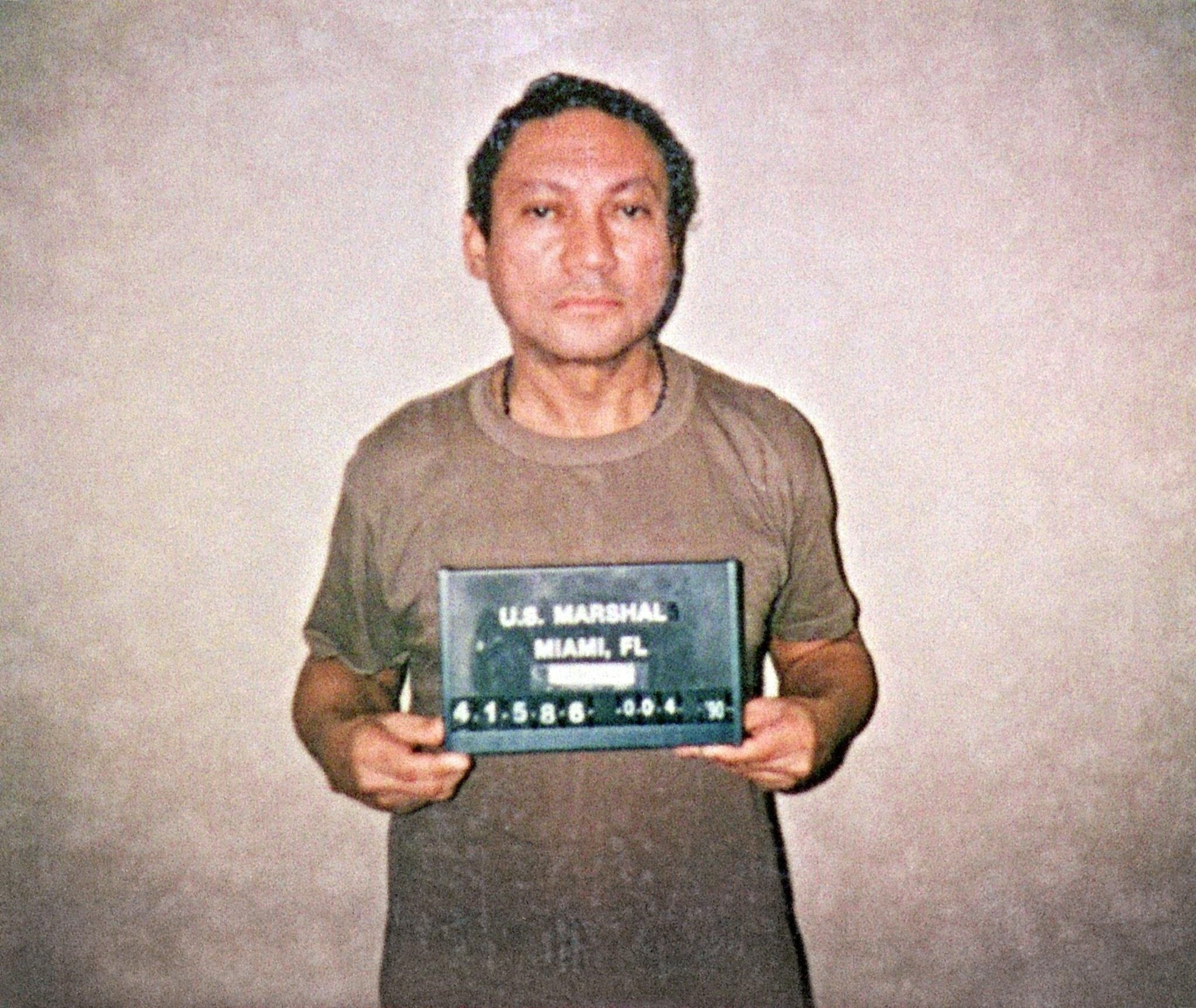

After the invasion, Noriega was captured and taken to Miami. In April 1992, he was convicted of drug trafficking and other charges. He served 17 years in a U.S. prison before being extradited to France to face money laundering charges. But because he also faced more serious charges back home in relation to the killings of his political opponents, France returned Noriega to Panama in mid-2011.

When news of the larger-than-life strongman's death was announced on Monday, Panamanian President Juan Carlos Varela tweeted in Spanish: "The death of Manuel A. Noriega closes a chapter in our history. His daughters and his relatives deserve to mourn in peace."

But the decision to support Noriega left a lasting mark on the U.S. record of supporting democracy, author Dinges said.

"If you lie down with dogs, you wake up with fleas. If you support dictators, you're going to be tainted by the crimes of those dictators," Dinges said. "To this day, people don't trust the United States to take a principled position to defend democracy.

"For example, Trump definitely seems to have a warmer relationship with the authoritarian rulers of the Middle East, who are not democratically elected, than the democratically elected leaders in Europe,” he added.

"This is a legacy of the time when, for trivial reasons, we would go into Latin American countries and get rid of governments that weren't to our liking.”