Threat of violence at home spurs LGBT migrants on to the border

A group of LGBT people arrived in Tijuana and said they will seek asylum.

A group of LGBT migrants was among the first members of the so-called caravan to arrive in Tijuana this week, seeking asylum from some of the most violent countries in the world where gay and trans people are particularly targeted, according to Amnesty International.

"We came with the caravan, and the caravan continues," Cesar Mejia told reporters in Tijuana earlier this week.

Mejia said their group included about 80 people, including children, from Honduras, Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala. As the week continued, hundreds of more migrants arrived in Tijuana, the Associated Press reported, although the majority of the caravan still appears to be more than 1,000 miles away.

A greater threat of violence

From the outside, many don't understand why people -- including families with small children -- would risk their lives to get to a country that has explicitly said it will not let them in. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has said that people in the caravan will not be able to enter the U.S. illegally "no matter what," and many members of the Trump administration, including the president himself, have accused members of the caravan of being terrorists or gang members.

Many migrants have said that what spurs them on are the terrible conditions at home: Central America is wracked with violence and poverty, corruption and impunity.

But for LGBT migrants, the threat of violence is, in many cases, even greater, a 2017 Amnesty International report found, and "gay men and trans women are exposed to gender-based violence at every point on their journey in search of protection." Amnesty listed Mexico and Honduras among seven countries it finds as being deadly and discriminatory for LGBT people.

Mejia, 23, told reporters in Tijuana that the LGBT members of the caravan gravitated toward one another in search of support. For his part, Mejia was easy to find in the crowd. When ABC News spoke to him last month in the tiny town of Huixtla, Mexico, he was wearing a rainbow flag around his shoulders.

"At first I was afraid to wear the flag. I didn’t know how people would react," Mejia told ABC News in Spanish. "In Guatemala, people were asking me what country the flag was and I told them it was the flag of the world."

But in his hometown of San Pedro Sula, Honduras, it was not viewed that way, he said.

"I was discriminated and beat up so it was time to go," Mejia explained.

He chose to join the caravan of thousands of other people, the majority of whom were also from Honduras, making their way to the U.S. border in the hopes of a better life.

Mejia said if he is able to make it to the border, he could make the case for political asylum.

"If I had the opportunity to make it to the border, I could show my representation of the community and ask for asylum, because [in the U.S.], there is a lot less discrimination than Honduras," he said.

Unable to speak out

Raul Valdivia, a gay man and human rights activist who still lives in Honduras, said he understands that discrimination firsthand.

"I've suffered many instances of discrimination based on my sexual orientation, but I remember the most violent came from state forces," Valdivia told ABC News. "I was abused by police while on one of my very first dates. They took me and the other guy to a dark secluded area in a park and forced us to simulate sex. They also beat us with a belt. These are police who patrol downtown Tegucigalpa and I have seen them after, but I'm unable to speak out for fear of repercussions."

Valdivia said LGBT people in his country face "assassinations, political attacks, legal discrimination and targeted street violence."

The country also has one of the highest homicide rates in the world outside of a war zone, according to the Overseas Security Advisory Council (OSAC). Authorities sometimes use gang violence as a cover for political and gender-based violence.

Nearly two thirds of Hondurans live in poverty, according to the World Bank. Corruption is a major issue, prompting the government to establish the Mission to Support the Fight against Corruption and Impunity in Honduras (MACCIH) in 2016 through an agreement with the Organization of American States, but much remains to be done.

"Marred by corruption and abuse, the judiciary and police remain largely ineffective. Impunity for crime and human rights abuses is the norm," a 2018 Human Rights Watch report found.

Those who choose to speak out face harsh reprisals. In 2016, U.N. experts called it "one of the most hostile and dangerous countries for human rights defenders." Human rights defenders routinely "suffer threats, attacks, and killings," Human Rights Watch found.

No change at the ballot box

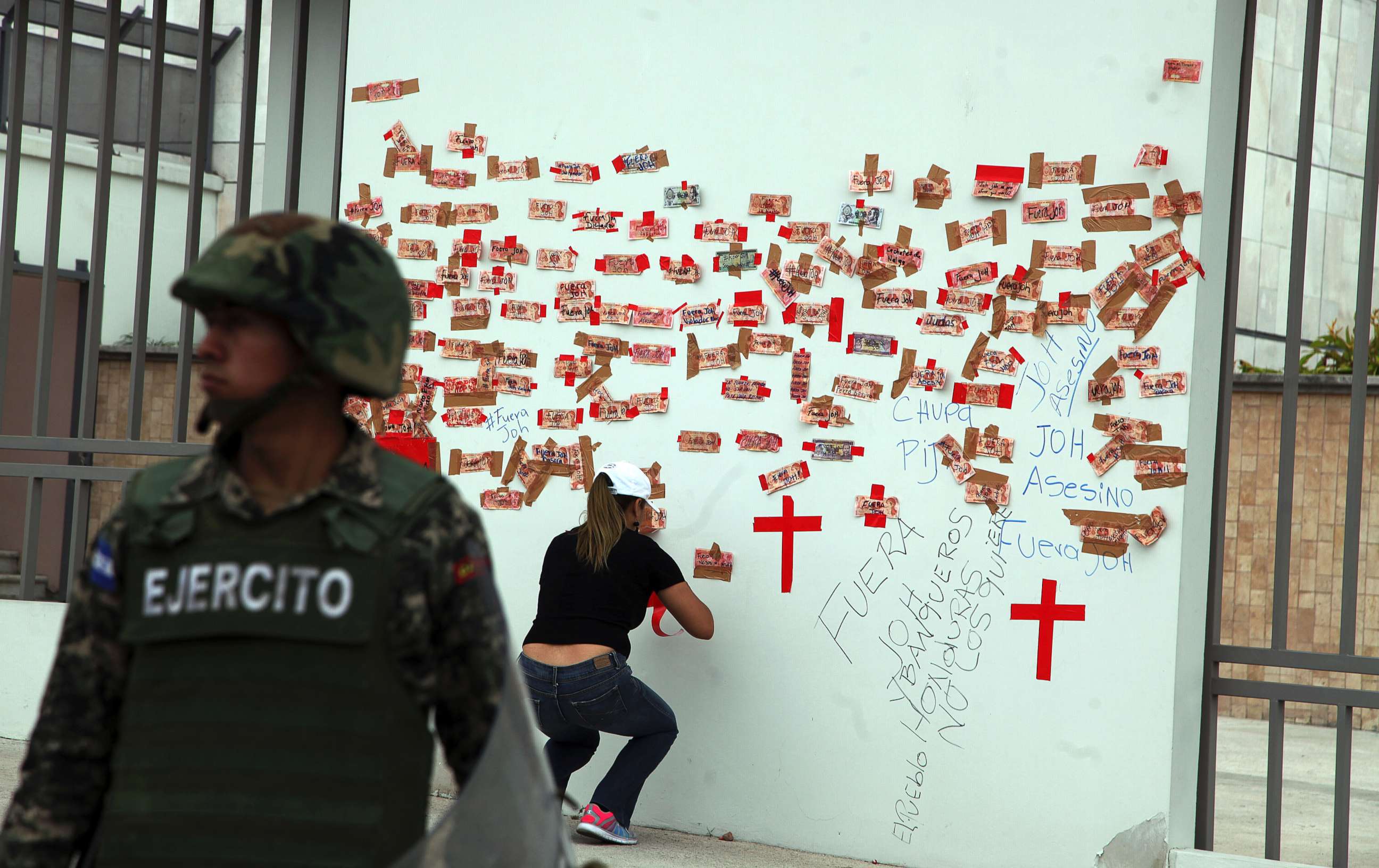

In November 2017, the country held a presidential election with widespread reports of fraud and violence. Thousands took to the streets to protest the re-election of Juan Orlando Hernandez, who changed the constitution to allow himself to run again.

The government's "response to the post-electoral protests led to serious human rights violations," according to the U.N., and dozens were killed and more than 1,000 were arrested.

Unable to change their country at the ballot box, many Hondurans chose to flee. And experts say that although the size of this caravan has grabbed headlines, many more Hondurans quietly flee the country every year, leaving conditions that have dramatically worsened since the 2009 military coup, especially for LGBTQ people, journalists and human rights activists.

In 2009, gay human rights activist Walter Trochez, 25, was killed in Tegucigalpa after trying to draw attention to anti-LGBT violence by security forces.

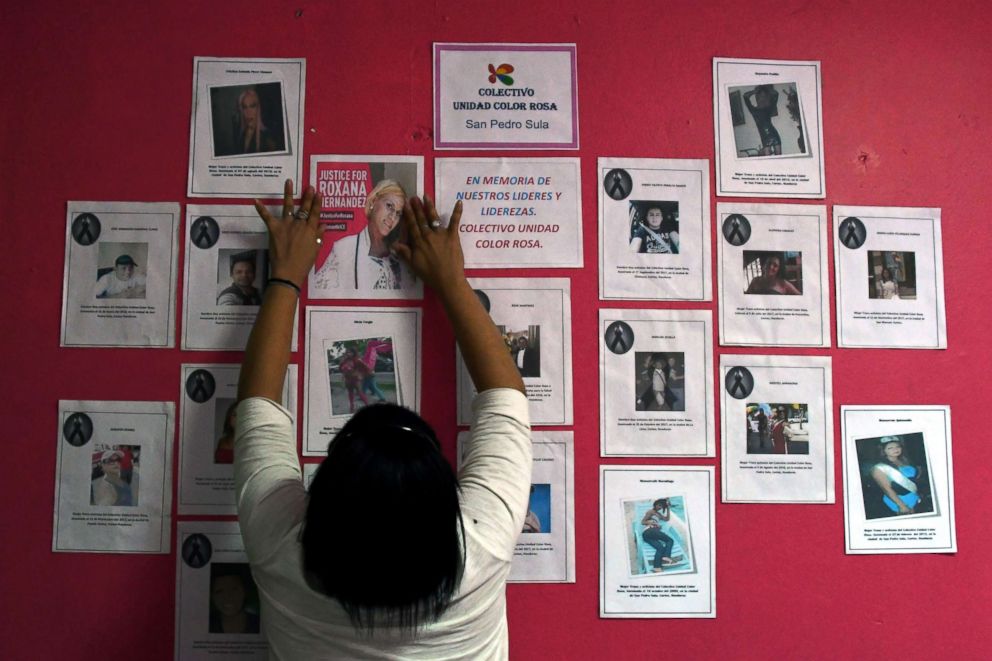

In July 2017, David Valle, project coordinator of the Center for LGBTI Cooperation and Development, was stabbed in his home after receiving threats, Human Rights Watch reported. He survived the attack, but it highlighted the deadly violence LGBT people face in the country.

It is this environment that has prompted Hondurans to risk their lives on the journey north, both in caravans and on their own, experts say.

"As impressive in size as this caravan may be, it still represents a minute proportion of Central Americans -- today primarily Hondurans -- that are fleeing their communities," Alex Main, the director of international policy at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, told ABC News.

Policies spurring an exodus north

But LGBT migrants and asylum seekers face dangers along the way, the Amnesty International report found, and often face discrimination and neglect in detention facilities as well. In May, Roxana Hernandez, a 33-year-old trans woman from Honduras, died while in ICE custody in New Mexico, the Associated Press reported.

Activists said she had traveled in a migrant caravan to the U.S. border. Hernandez had been admitted to the hospital after showing symptoms of pneumonia, dehydration and complications associated with HIV, the AP reported.

But even facing extreme dangers along the way and an uncertain future in a country whose president says it does not want them, people have continued to flee Honduras. That will continue until there are real policy changes, Main said.

"This mass exodus will only abate when the rampant violence in Hondurans abates, and when real economic development begins to take hold. This will require a profound revision of current economic models promoted by the U.S. and multilateral financial institutions and the displacement of a corrupt economic elite that retains power through repression and electoral shenanigans," Main added.

Until then, migrants, including those in the LGBT community, will continue to trek to the U.S., as this recent caravan has.

More than 2,600 migrants made it Tijuana Saturday, according to the Associated Press.

Mejia said he hopes his group's early arrival will give them an advantage with border officials.

"We wanted to avoid what always happens, which is that if we arrive last, the LGBT community is always the last to be taken into account in everything," he said at a press conference Sunday. "So what we wanted to do is change that, and to be among the first, God willing, and request asylum."