9/11 commission official calls on government to change response to coronavirus immediately: OPINION

Congressional food fights and finger-pointing have thwarted U.S. response.

"We're here today to find out how many people will die based on the decisions you make."

Over a decade ago, beginning with words like those, I led a "war game" exercise involving senior officials from several states and the federal government. We were trying to determine what would happen if a weaponized microbe, like anthrax or smallpox, were released into the general population.

As the exercise proceeded and hypothetical people started to become ill and die by the thousands, the soft underbelly of American preparedness became apparent: The capacity of our public health resources was no match for a pandemic.

The point of such exercises, of course, is to push the limits of our government's capabilities to the breaking point, so that we would be better prepared for worst-case scenarios in real life. Our goal, to put it bluntly, was to challenge the response until mass hypothetical casualties occurred. It wasn't very hard to accomplish that.

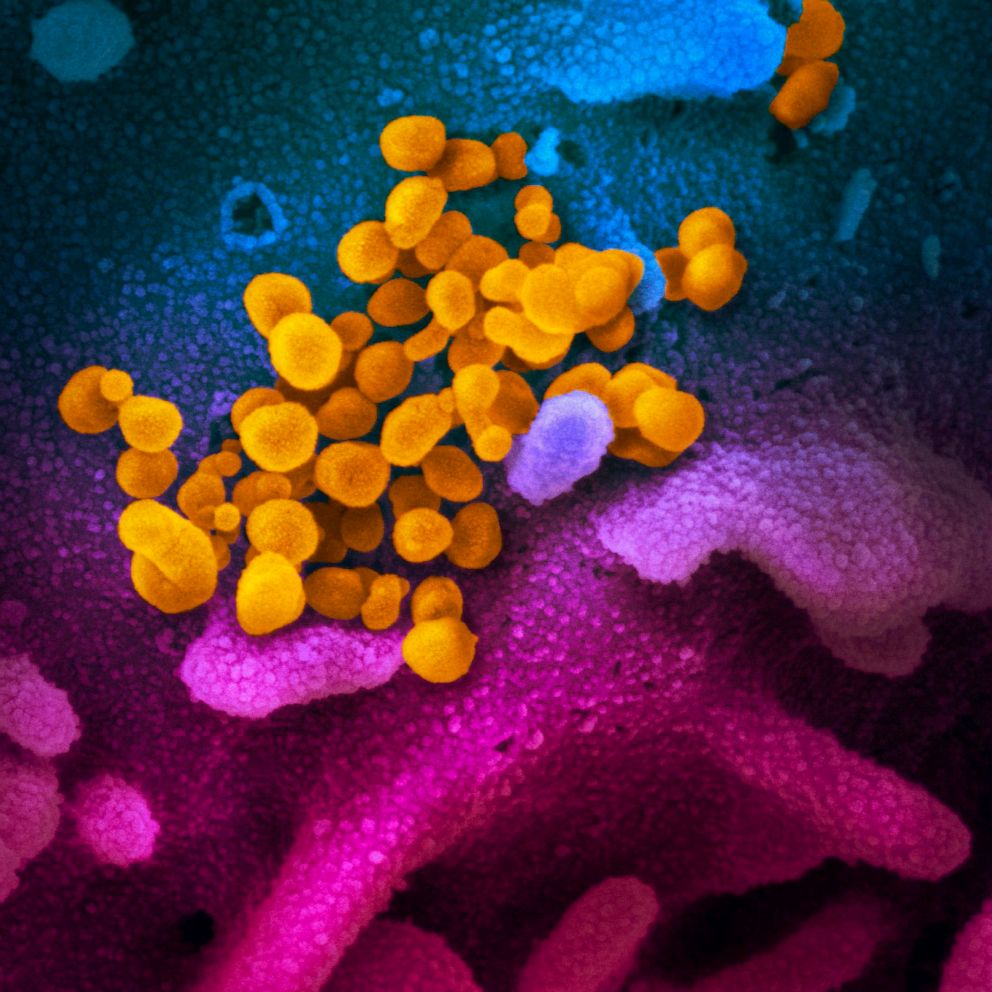

As the years have passed and both the risk and frequency of pandemics have increased, I had been comforted that the response of the world public health effort seemed up to the task. As one truly lethal zoonotic or pathogenic disease after another (HIV, Zika, Ebola, MERS, West Nile, SARS) emerged, flared for a time, and then was managed, it appeared that this most dangerous aspect of globalization and development -- the likelihood of pandemics emerging -- had been adequately anticipated in our nation’s emergency planning. We were tracking the viruses closely, and we knew how to achieve containment through contact surveillance, quarantine and isolation.

Then came COVID-19.

The finger-pointing has already begun in the midst of this pandemic. The Trump administration has been singled out for its lethargic response and for previously dismantling a top-level National Security Council office dedicated to coordinating the government response to pandemics. President Donald Trump has pointed to the Chinese reluctance to share information early in the outbreak, and to the Obama administration for its alleged negligence on the preparedness side.

The partisan squabbling and nationalist agitation are not surprising, but will accomplish nothing other than a deepening of the polarization that has paralyzed American politics for a generation, preventing us from reaching consensus on issues as fundamental as infrastructure, immigration and health care.

As with prior catastrophic failures of the government to protect the American public, such as Pearl Harbor, 9/11 or Hurricane Katrina, the public will demand -- and good government will require -- an accounting of the actions and inactions that contributed to the world's -- and our nation's -- failure to contain the COVID-19 pandemic.

The questions, then, are how to do it right, and when?

First, to be constructive, the effort must be removed from congressional politics. A middle school cafeteria food fight is more civilized than some recent congressional exchanges. Congress can contribute to a solution by creating a mechanism empaneling nonpartisan experts to find the facts. Precedent for the value of this approach can be found in the 9/11 commission. Perhaps a better approach, especially if the government seems reluctant to act, would be for the nation's and the world's research universities to convene a panel to reconstruct the failure to contain COVID-19 and evaluate the ongoing efforts to mitigate it.

Second, it should be made clear that, however the panel is constituted, its mission is not to apportion blame but to set forth the facts surrounding the novel coronavirus pandemic and to identify lessons learned that tie closely to those facts. This recommendation will be controversial. Hundreds of thousands -- perhaps millions -- may die. Survivors will want someone to blame. The 9/11 commission report left the blame game to others; that is one of its enduring strengths. Assigning blame would distract from the essential task of fixing the response now.

Third, the panel's recommendations must be tied closely to the facts it finds and the needs it discovers. This might seem self-evident, but reports produced in the helium atmosphere of our nation's capital tend to float immediately to 30,000-foot pie-in-the-sky irrelevance if unanchored to grounded truths: What happened precisely? How did it happen? Why? What should have happened? Why didn’t it?

Fourth, and perhaps the greatest challenge, is that the work must be done right now. In the case of prior disasters, the accountability inquiry occurred after the acute moment of crisis had passed. We don't have that luxury this time.

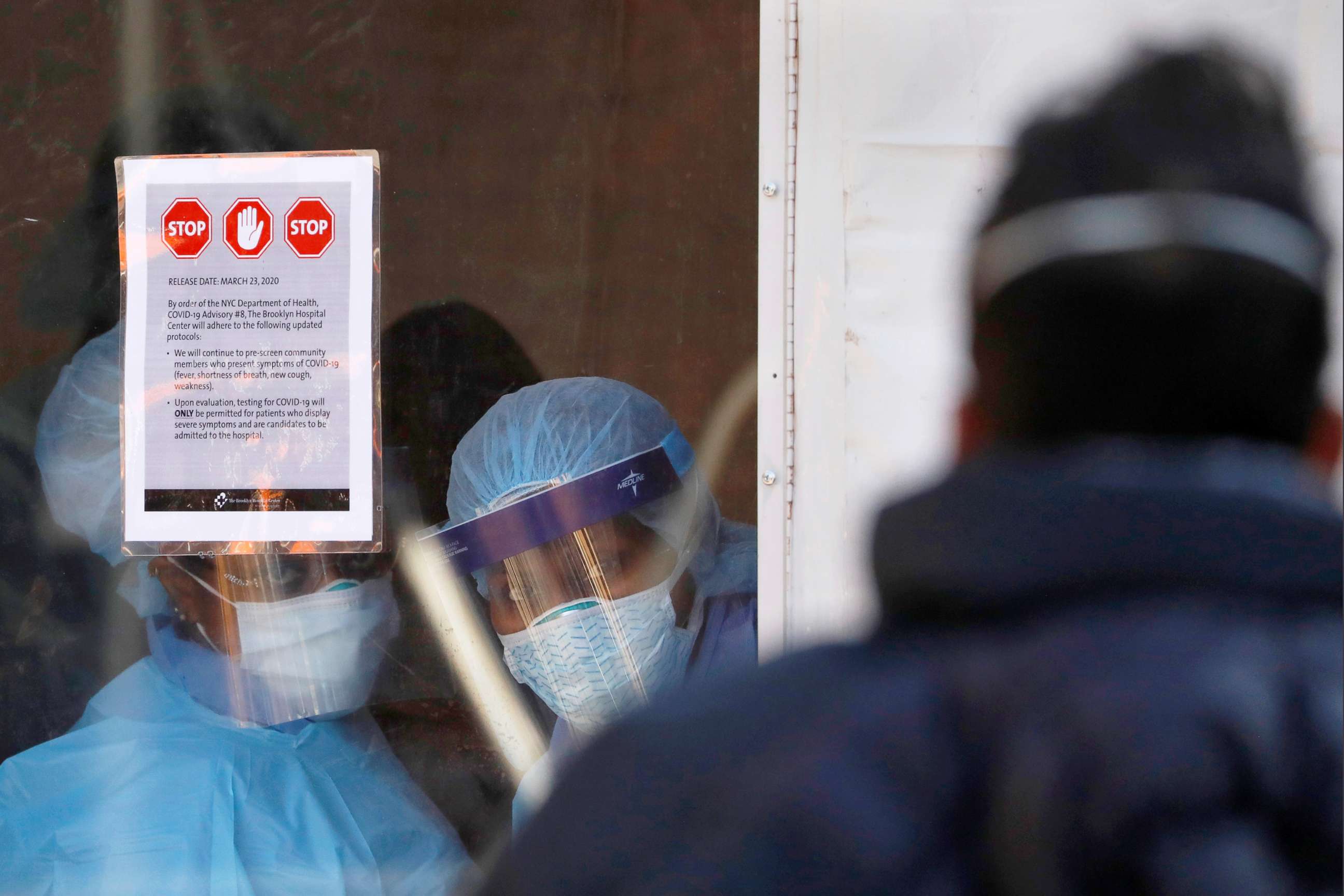

This approach is sure to be resisted. After all, who has time to evaluate the response while the response is still occurring? But the response to date, no matter who bears responsibility, has been nothing short of calamitous. Our failure to test aggressively has left us blind to the spreading presence of the pandemic.

Because our ignorance is so vast, we are unable to mitigate the virus' effects unless we are willing to commit economic suicide. Our failure to plan at any level of government has left municipalities, states and the federal government fighting one another for masks, robes and fundamental equipment, like ventilators. Guidance to the general public has been from a cacophony of competing and inconsistent voices, leaving people genuinely confused about what restrictions are mandatory or whether they are even necessary.

Our national emergency response system, which rests on the normally sound assumption that governors are best equipped to make critical decisions, has been overrun by a global pandemic that by definition respects no political boundaries.

People are dying by the dozens, and the rate is increasing; some estimates are that upward of 500,000 Americans may die, and the economy will take years to recover.

And so, I return to my question of so many years ago: How many people will die based on the decisions you make? People are dying by the thousands based on the decisions our leaders have either made or avoided making in response to this evolving pandemic.

We need to stop this. We need a mid-course correction, based on evidence and facts, and we need it now.

There is precedent for such an approach, as during the war in Iraq, when Gens. David Petraeus and Stanley McCrystal assembled teams of experts to rethink in real time the way that war was being fought, a nonpartisan panel must ask and answer in real-time whether there is an evidence-based and more-effective chain of command to combat this uncontained global and domestic pandemic.

The urgency of the moment demands that the effort take place now. Even as the novel coronavirus matriculates uncontained and kills thousands, the next contagion lurks in some obscure corner of the globe, waiting to break out.

John Farmer Jr., a former attorney general of New Jersey, was senior counsel to the 9/11 commission and lead investigator on the commission’s team that examined emergency response and preparedness. He is the director of the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers University.