Acting Interior chief faces confirmation hearing as critics say department is too close to industry

Critics call Bernhardt the "ultimate D.C.-swamp creature."

Soon after being appointed to the Interior Department in 2017, acting secretary David Bernhardt kickstarted a plan to change how California handles water in a way that would benefit farmers and businesses.

It was a step toward the same goal he'd pursued as a private lawyer and lobbyist.

The move by Bernhardt, whom President Donald Trump handpicked to oversee the nation's parks and public lands, is a sticking point in his nomination. He testifies Thursday before the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee.

Ethics officials at Interior recently cleared Bernhardt of violating rules to prevent conflicts of interest in the California case, but advocacy groups that are critical of Interior under Trump have called him a "walking conflict of interest" and the "ultimate D.C.-swamp creature" for his ties to the oil and gas industries and energy companies.

In the California case, Democrats and advocates questioned whether Bernhardt had a conflict of interest in the issue because he previously represented a water district that sued the government to have more water diverted its way.

One of the most vocal Democratic critics of the Interior Department is Rep. Raul Grijalva of Arizona, chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee. He said industry groups have made "massive inroads" to the department through political appointees in leadership positions, and that a lot of the rollbacks are changes oil and gas companies have been seeking for a long time, like expediting permits and environmental decisions and taking shortcuts on reviews for endangered species.

"The list goes on," he told ABC News. "The rolling back of regulations and processes, the short-circuiting of necessary scientific and environmental review and impact statements. So all that is happening and I don't think it's happening in a vacuum, all of this is ongoing."

The department has consistently defended Bernhardt, saying he follows ethics rules and advice from the agency's lawyers.

"The Acting Secretary is scrupulous in complying with his ethics agreement. To do so, he appropriately and consistently seeks guidance from career ethics experts and follows their advice to the T," Interior spokeswomen Faith Vander Voort said in a statement.

Bernhardt, 49, is best known as an industry lawyer and lobbyist who worked with industry groups and energy companies, sometimes against the federal government. He also worked at Interior in the solicitor's office from 2001 to 2009.

The New York Times reported that he made policy decisions that favored private industry -- a practice critics point to as part of what they see as a trend in this administration. The Times reported Bernhardt and other political officials with ties to chemical companies worked to suppress a study from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service that found most endangered species in the U.S. are threatened from the use of pesticides in the country.

The story cited emails and other internal documents released through a Freedom of Information Act request, which The New York Times posted and were reviewed by ABC News.

House Democrats, citing the report, wrote to Bernhardt on Tuesday calling for the study to be released immediately.

The Interior Department told the Times that Bernhardt was acting on legitimate concerns about the evaluation.

Trump campaigned on a promise to "Drain the Swamp." But his administration has faced persistent criticism for relying on former lobbyists and other people with ties to business and the private sector instead of career civil servants.

At the Interior department, critics and environmental groups have accused several of these officials of decisions that would financially benefit industries like oil and gas at the expense of the environment.

Scrutiny amped up significantly after former Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price and former EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt were accused of ethical lapses and excessive spending on travel. Both ultimately resigned.

Former Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, whom Bernhardt is vying to replace, was also accused of conflicts of interest but was not found guilty of major violations by the department's inspector general. He resigned before all internal investigations were complete.

The nonpartisan watchdog group theCampaign Legal Center has raised questions about whether at least six other officials at Interior are also working with former clients or violating ethics guidelines.

Jeff Holmstead, a former EPA official who worked under Bush, said he's seen these kinds of allegations regardless of administration and even faced them himself.

"People who are critical will always look for every way they can to oppose something they think is bad policy and charges of ethics violations are always leveled," he told ABC News.

Holmstead argues that the government needs the expertise of people who have worked in the private sector, which is exactly what the ethics rules are meant to address.

"If you prohibited people from ever working on the same issues in the government that they worked on in the private sector the public would never benefit from that experience so I think that's an important thing," he told ABC News.

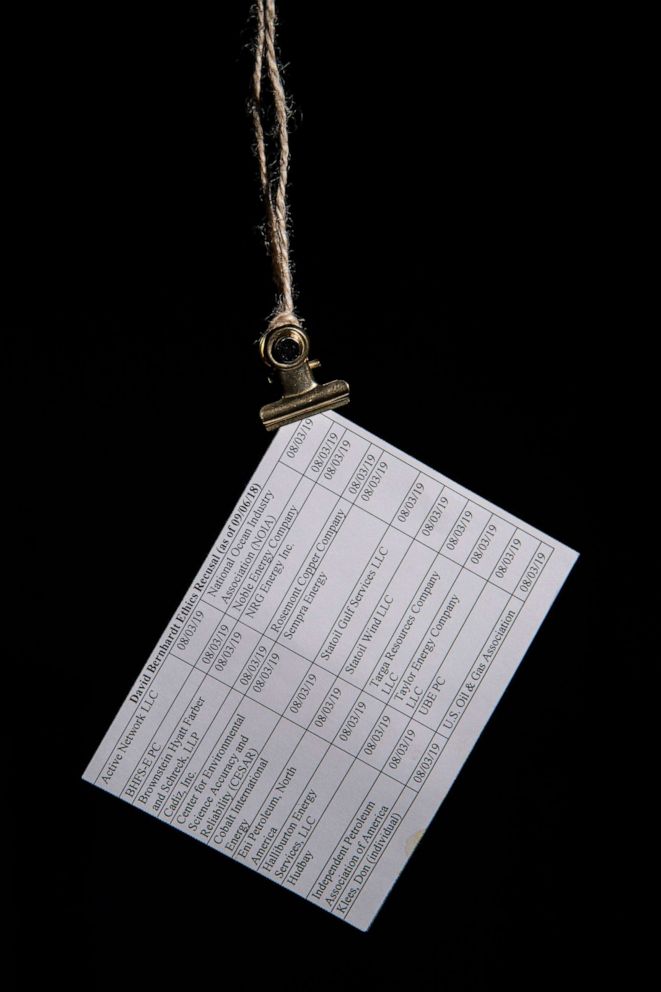

Bernhardt's past experience is such that ethics officials have required that he recuse himself from meeting with 22 separate groups because of previous employment ties, according to documents from the agency's ethics office obtained by the watchdog group American Oversight, a liberal watchdog group. The Washington Post reported he even carries a card listing all the recusals to help him keep track, which advocacy groups frequently use to criticize his ties to industry groups that could benefit from the department's decisions.

"I will follow all of the recusals I have and on top of that, if I get a whiff of something coming my way that involves a client or a former client or my firm, I'm going to make that item run straight to the Ethics Office. And when it gets there, they'll make whatever decisions they're going to make and that will be it for me," he testified at the time.

Before coming to the department as deputy secretary, and now acting secretary, Bernhardt represented Westlands Water District, which has sued the federal government saying more water should be diverted to farmers. But documents provided to ABC News show ethics officials at Interior determined the decisions to re-evaluate water management in the Central Valley Project are broad enough that Bernhardt is not required to recuse himself, even though it directly impacts a former client.

Westlands Water District did not respond to requests for comment from ABC News.

In February, Bernhardt confirmed to The New York Times that he ordered the agency to rethink how the federal government weighs the need to protect rivers for endangered species of fish in California against the needs of farmers and cities in other parts of the drought-stricken state.

Groups that have fought to protect the endangered species in California rivers say Bernhardt is using his position to push policies that benefit his former client. If the change is finalized, the Trump administration would reverse course from warnings under the Obama administration that more actions were needed to protect a struggling ecosystem.

"Mr. Bernhardt first tried and failed to weaken environmental protections through litigation on behalf of Westlands, then he was largely unsuccessful in doing so through Congressional lobbying on behalf of Westlands, and now he's trying again, only this time from inside the Trump Administration," Doug Obegi, a lawyer for the Natural Resources Defense Council, told ABC News.

Grijalva has been pushing the Interior Department to release Bernhardt's full schedules, saying Congress and the public can't hold him accountable if they don't know who he's meeting with and what they talk about. In an earlier response Bernhardt wrote that he didn't keep a personal calendar, but on Monday night the department provided the committee with almost 7,000 pages of documents including his daily schedule compiled by staff.

"Mr. Bernhardt is a former lobbyist for multiple industries, oil, gas, and those companies fortunes, they rise and fall with decisions that are made at Interior. So as somebody who wants to lead this agency he has a responsibility to provide all the documents that are being asked," Grijalva told ABC News.

Lawmakers in recent weeks have asked Interior's internal watchdog to look into whether Bernhardt's order on the California water issue violated ethics rules.

Bernhardt has said he agrees the Interior Department's ethics approach needs an overhaul, even though he says his decisions were approved by ethics officials. A recently released report found the ethics office was understaffed to the point that one employee was responsible for more than 300 financial disclosures during the administration's transition into office.

In a Feb. 1 memo to staff, Bernhardt said the "cavalier culture of ethics compliance" is not the Trump administration's fault. He said they are actually working to improve ethics training at the department, including staffing up the ethics office.

"Our organization's ethics challenges were part of a mess that we inherited," he wrote in a February memo to employees, adding that even top officials have been cited for violating ethics rules. "The last decade of inspector general's reports read like an avalanche of ethical misconduct."